BROUGH SUPERIOR

Lawrence of Arabia Couldn't Have Found A Better Way To Die

BY DENNIS MAY

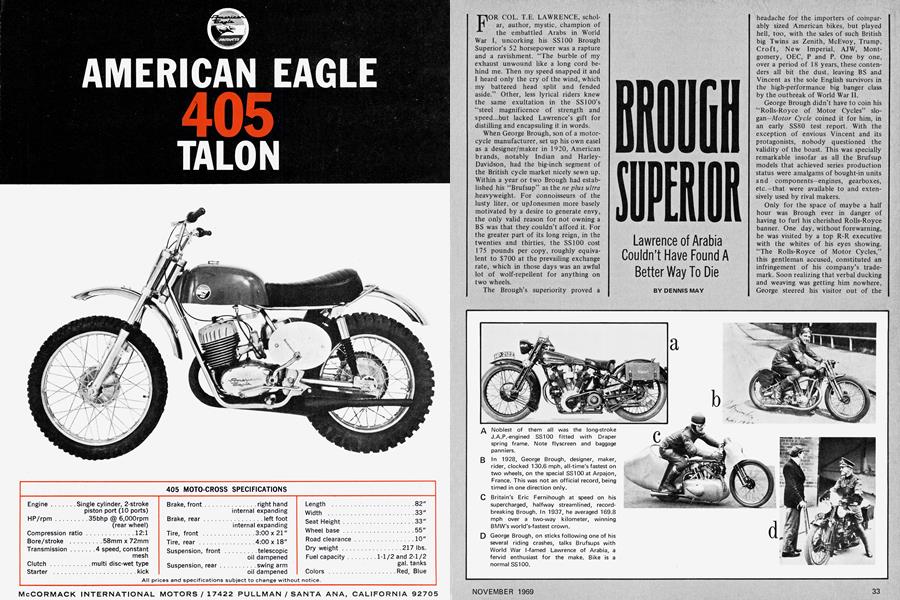

FOR COL. T.E. LAWRENCE, scholar, author, mystic, champion of the embattled Arabs in World War I, uncorking his SS100 Brough Superior’s 52 horsepower was a rapture and a ravishment. “The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Then my speed snapped it and I heard only the cry of the wind, which my battered head split and fended aside.” Other, less lyrical riders knew the same exultation in the SS100’s “steel magnificence of strength and speed...but lacked Lawrence’s gift for distilling and encapsuling it in words.

When George Brough, son of a motorcycle manufacturer, set up his own easel as a designer/maker in 1920, American brands, notably Indian and HarleyDavidson, had the big-inch segment of the British cycle market nicely sewn up. Within a year or two Brough had established his “Brufsup” as the ne plus ultra heavyweight. For connoisseurs of the lusty liter, or upjonesmen more basely motivated by a desire to generate envy, the only valid reason for not owning a BS was that they couldn’t afford it. For the greater part of its long reign, in the twenties and thirties, the SSI00 cost 175 pounds per copy, roughly equivalent to $700 at the prevailing exchange rate, which in those days was an awful lot of wolf-repellent for anything on two wheels.

The Brough’s superiority proved a headache for the importers of comparably sized American bikes, but played hell, too, with the sales of such British big Twins as Zenith, McEvoy, Trump, Croft, New Imperial, AJW, Montgomery, OEC, P and P. One by one, over a period of 18 years, these contenders all bit the dust, leaving BS and Vincent as the sole English survivors in the high-performance big banger class by the outbreak of World War II.

George Brough didn’t have to coin his “Rolls-Royce of Motor Cycles” slogan— Motor Cycle coined it for him, in an early SS80 test report. With the exception of envious Vincent and its protagonists, nobody questioned the validity of the boast. This was specially remarkable insofar as all the Brufsup models that achieved series production status were amalgams of bought-in units and components-engines, gearboxes, etc.-that were available to and extensively used by rival makers.

Only for the space of maybe a half hour was Brough ever in danger of having to furl his cherished Rolls-Royce banner. One day, without forewarning, he was visited by a top R-R executive with the whites of his eyes showing. “The Rolls-Royce of Motor Cycles,” this gentleman accused, constituted an infringement of his company’s trademark. Soon realizing that verbal ducking and weaving was getting him nowhere, George steered his visitor out of the office and into the little factory itself, where handpicked artisans were prepping a bevy of Broughs for the upcoming motorcycle show at Olympia, London. To protect the machines’ jewel-like finish from fingerprinting, these operatives were working in white gloves. A 20-minute tour of inspection turned the trick, and permission to continue using the slogan, infringement or not, was graciously granted.

Counting models that either progressed no further than the prototype stage or were built in negligible numbers and died young, Brough Superior was, for an operation of its size, notable for almost riotous design diversification. George’s true masterpieces were the big V-twins of normal configuration™ mostly 1000-cc gallumphers with their cylinders lying on their north/south axes: the MK Is and Ils, the SS80s, the yummy SSI00s in a wide variety of subtypes, the 11-5Os with a capacity of around 1100 cc, cylinders at the unusual angle of 60 degrees and an output ranging between 30 and 37 bhp.

Apart from the fact that their finish and workmanship was superlative and their detail design a delight, these BSs were all, in varying degrees, beautiful rather than merely pretty. George Brough disdained styling gimmicks; always his aim was pure practicality, and from this his machines’ beauty proceeded as infallibly as night follows

days. Even his almost sexily curvaceous gas tank was only secondarily the result of aesthetic striving; its bulbous shapeoften copied but never quite successfully-was primarily inspired by the need to reconcile long-range gallo nage with sensible length and width dimensions. While at least no worse than average in their class for top end accessibility, all the big Twin Broughs, and the ohv ones in particular, were standouts for compactness, devoid of unsightly gappiness, cunningly cramming multum into parvo.

The first Brough Superiors, designated MK I, made their debut in 1920 and for a few years were coexistent with the unsuffixed Broughs designed and built by George’s father, W.E. (Bill) Brough. Pre-BS, both before and just after World War 1, George had been W.E.’s partner in the latter’s small but respected firm, in the East Midlands region of England. The W.E. Brough company, remembered for its high quality 500-cc flat Twins, survived until 1925, then folded. The Broughs were Nottingham people and when George struck out on his own he built and moved into independent premises on Haydn Road in the same city.

The Mk I, with its labyrinthine exhaust plumbing (silencer ahead of the crankcase) over attenuated tank and perched-up saddle, was perhaps the homliest of all Brough Superior Twins,

albeit its vertical valved J.A.P. engine (90 by 77.5 mm) gave it an appealingly rugged stamp. This pushrod ohv clock work was a leftover from J.A.P.’s prewar repertoire, foreshadowed modem over square cylinder dimensions and originated the burbling, dark exhaust note that was to become the standard BS lingo. In overall design the Mk I was conventional, having a diamond (i.e. non-cradle) frame, a three-speed Sturmey-Archer gearbox, Brampton forks with a form of linkage involving wheelbase variations under compression and decompression, and brakes of (in English parlance) dummy belt rim type. At a time when the weather-sensitive and fragile belt was still a widely accepted transmission medium in England, this BS used chains. An optional 85.5by 85-mm flathead J.A.P. could be ordered in place of the 90-bore ohv.

Also in 1920 came the ultra refined Mk II, powered by a Swiss M.A.G. engine of narrow angle v-form, with its exhaust valves in the block and overhead inlets. Rocker gear and pushrods were totally enclosed. These M.A.G.s, like all the bought-in engines ever fitted to BSs, were modified in detail by their makers to George’s exacting demands. They came in two displacements, 748 and 996 cc, and, although lacking the competitive J.A.P.s’ brutal performance, had a suavity that was all their own.

A third variation on the early Brufsup theme was a model featuring the Barr and Stroud sleeve valve engine, a 50-degree V-twin measuring 86 by 86 mm. Its “great charm and delight,” as Ronald Clark, the biographer of the BS, was to write in his fine book, The Rolls-Royce of Motor Cycles, “was the total absence of poppet valves, tappets, guides, camshafts, and all the noise associated with these impedimenta.” Less charming and delightful was the problem, never successfully solved, of lubricating the vital sleeves, and consequently the Barr and Stroud soon stood revealed to George its serious shortcoming.

Brough had started his competition riding career at age 16; he rode one of his father’s Broughs in the 1906 End to End Trial, i.e., from balmy Cornwall to John ’o Groats in northernmost Scotland, completing the course three days behind the next slowest finisher. With a background like this (it also included a dnf in the 1913 Senior TT, again on a W.E. Brough product) it was natural that on reaching man’s and manufacturer’s estate he should develop a bent for “hardy sport and contest bold.”

His first personally owned racing Brufsup, known originally as “Spit and Polish” but later, following wholesale development and modification, as “Old Bill,” formed the foundation of the production SS80. Making ample amends for its rider’s End to End and TT failures, “Old Bill” was almost uniquely successful in speedwork, being the first sidevalver to lap Brooklands track at 100 mph and winning 51 of 52 straightline sprints contested. The one it missed out on, at the Clipstone Drive strip, ended painfully when the front tire burst at 110 mph, close to the finish line. It’s even arguable that it won this 52nd encounter as well, for the bike itself covered the course 2.2 sec. faster than the next fastest, but not so the bloodied and recumbent George, one of whose forearms finished up “hanging by a strip,” as he describes it.

The model prefix SS, which was to have Brufsup associations lasting as long as the make itself, dates from 1923 and the majestic SS80’s launching. A year later, at the Olympia Show of 1924, George sprang the even faster, more sumptuous and expensive SSI00. Both these lines, changed almost beyond recognition in the course of years, were still in production when BS cycle production ceased on the outbreak of World War II.

The natal SS80 was a diamondframed 1000-cc sidevalver, a giant stride ahead of the old Mks I and II in looks and handling. Its 85.7by 85-mm J.A.P. engine, known as the 8-30 because of its 8 rated and 30 brake horsepower, had four cams (Mks I and II had two) and gave the bike an 80-mph maximum. Forks again were girder type Bramptons. Enticing features included finned cast aluminum exhaust manifolds and dual “lampglass” silencers terminating separate large bore pipes, both on the same (right-hand) side of the machine.

The SSI00 was something else entirely. J.A.P. had recently released an all new V-twin, replete with inclined ohv, hemi heads and an output of 45 bhp from 980 cc. Type numbered 8-45, this magnificent powerplant snugged into the SS 100’s compact cradle frame with hardly a whisker to spare. By 1925, every SSI 00 carried a written guarantee that it had done 100 mph or better over the flying quarter mile before delivery.

The SSI00 was in debt to America for just one feature, but it was an important one-its Harley-inspired, leading link Castle forks. With their low unsprung weight factor and good lateral rigidity, these were superior to any rival British product of their day. Early SSI00s were distinguished by an unusual elevated exhaust system, with the pipes just above hub level but on opposite sides of the machine. The forks were surmounted by a flyscreen that looked too small to do much more than prevent your navel catching a cold, though it actually possessed useful wind-deflecting properties at speeds above 70. As on all Broughs of all vintages, the gas tank was nickel plated (chromium in later times) with its upper surface enameled black to prevent reflection; elsewhere, brightwork was sparingly used. It’s on record, though, that one customer, an Eastern potentate, insisted on having his bike silver plated all over.

it would require a tome to detail the many stages of development through which the SS100 passed in 14 years. First there was an engine switch when J.A.P. introduced the long-stroke 80by 99-mm engine in 1928; in spite of its reduced piston area, this one generated an extra 5 bhp. In 1929 came the first Brufsup excursion into rear springing with the optional Draper suspension. Its pivotal motion was controlled by twin coil springs located on each side of the saddle lug. The Draper system was most commonly specified on the SSlOO’s Alpine Grand Sports variant, a model name commemorating George Brough’s personal success in the eight-day Alpine Trials. The Draper device was later succeeded by a plunger type suspension of Brough’s own design.

Another SSI00 offshoot, intended primarily for racing but marginally streetworthy if silencers were fitted, was the hairy, highly tuned Pendine and its sister, the Pendine Special. The former used the 8-45 engine, the latter the 8-50.

In 1933, J.A.P. launched the elaborate 8-75 engine, developing, as the numerals imply, 75 bhp. Once again Brough was in at the newcomer’s birth, largely redesigning the SSI00 around it. An almost total departure from everything that had preceded it, the 8-75 featured high camshafts and short pushrods, deeply spigoted cylinders, twin carburetors on straight stubs, dual oil pumps, bevel drive from the front camshaft to paired magnetos. A four-speed gearbox, which had been standardized for the first time on the SS100 in ’32, acquired a positive stop shift on the 8-75 version of 1933.

Although most true votaries look back on the J.A.P. engine chapter of SSI00 history as the BS’s saturnia regna, George himself was finally sold on the superior refinement of the AMC engine. Inferior as it was in performance, he’d buy it as long as it spared his sensitive ears from the J.A.P.’s subdued but perceptible Musak of slapping pistons and bickering tappets. And buy it he did, in the fall of 1934, making it an option for 1935 et seq in sidevalve and ohv form on the new SS80 Special and SSI00, respectively.

Was there ever a bad BS? Solely by the performance yardstick, yes, there was: a low priced 680-cc flathead that George introduced in response to illjudged dealers’ demand in 1932. Only 10 copies of this paperback edition were sold. Other and more successful sub-liter Brufsups were a 750 sidevalver, sort of a poor man’s SS80; ohv J.A.P. Twins in 680and 750-cc calibers, the latter in effect a scaled-up version of the former; and another yet smaller J.A.P.-powered V-twin, the rare half-liter, only nine of which were built. Bachelor cylinders were anathema to the luxury loving George, but he did once unbend to the extent of building a single J.A.P. Single for a wrong headed customer.

Although Brough was, and in his 80th year still is, “a man of pregnant parts and quick inventive brain,” he always had too much sense to scorn the advice and collaboration of proven ingenious well-wishers, professional and amateur both. Harold Karslake, George’s partner in the Castle Fork and Accessories Company and a long-time Brough rider in trials, probably contributed more than Brough himself to the design of the famous Karslake-Brough prop stand-a marvelous muscle substitute for little riders of big bikes. Too, it would be impossible to exaggerate the value of the ideas on detail design dreamed up by the legendary Ike Webb, George’s factory manager from the start of the BS story until the last production bike was issued. Webb, a World War I Grenadier Guardsman who was to be awarded the British Empire Medal for his work on Brough defense contracts in World War II, incidentally notched up more than 175,000 miles on the BS he built for himself, using nothing but reject parts. George, for his part, was a believer in keeping close tabs on what the competition was doing, and had owned cycles of 34 different makes before even starting his Brufsup business.

(Continued on page 81)

Continued from page 36

At the outbreak of World War I, when the BS payroll stood at 19, the firm was to quit Haydn Road and migrate across town to the Vernon Road factory where W.E. Brough had made his Broughs in his lifetime and which, since 1925, had been operating as machine shops. Here, during the war, the labor force climbed to over 330, most engaged on the machining of crankshafts for Rolls-Royce Merlin aviation engines.

Few riders, once they’d become Broughians, were satisfied with anything else. One enthusiast is still running the BS he bought new in 1923. Lawrence of Arabia owned seven Brufsups in a row; a fool for mileage, he would sometimes leave Haydn Road on a newly shod SSI00 on a Friday night or Saturday morning and return Monday a.m. with a thousand fresh miles on the meter and a back tire as bald as Brynner. Alas, it was on a BS, through no fault of its or his, that he crashed to his death in 1935.

In total, but not counting models that never quite staggered over the prototype/production borderline, around 5000 BS bikes were built. Although the youngest Brufsups extant aren’t far short of 50 years old today, George says that “not a month passes without at least one veteran coming into the works with a request to make it look as much like a brand new BS as possible. The results, in appearance and performance, are nothing short of stupendous.”

Brough himself, although debarred from riding by a recent illness, is still much the same debonair, swashbuckling figure I first met more than 40 years ago, who loves to .cover ground with the wind in his hair. On the street he alternates between an E-Jaguar and one of the few surviving Brufsup cars, now coming up to its half-millionth mile. These cars, powered by Hudson engines, some of them blown, had a limited but successful production run in the mid to late thirties. Characteristically, George’s own example is a convertible.

Brough Superiors had more extensive and varied success in competition than any other British big Twin in history, excelling in English type trials, in straight sprints and hillclimbs, in Brooklands races, on sand, even on ice. In 1927, a fellow called Sluymers pulled an unusual feat by climbing the 7500-ft. Mount Merapi, an extinct volcano in Java, on an SS80. He spread the 18-mile ascent over two days, using up 12 hours the first day, five the second, and perforcedly staying in low gear the whole way.

Although countless races were won and records broken on Brufsups by such famed mahouts as Bert Le Vack, Fred Dixon, O.M. Baldwin, Joe Wright, Ron Storey, Ted Baragwanath, Alan Bruce, Eric Fernihough, Noel Pope and many others, George Brough was himself possibly the most versatile competition rider who ever threw a leg across a BS. He won trials awards galore, flattened all opposition, on “Old Bill” in sprints. Fleetingly, in 1928, he unofficially ranked as the world’s fastest rider, clocking 130.6 mph in one direction over the flying kilometer at Arpajon, France, but pulped a piston during the obligatory return run.

Brufsups repeatedly broke the world’s-fastest record officially, starting with Le Vack’s 119 mph in ’24 and ending with Fernihough’s 169.8 13 years later. The Nottingham projectiles were the first to lap Brooklands at 120 mph solo (Pope in 1935), turned the track’s first century average with sidecar (Dixon, circa 1930), finally set a solo Brooklands lap record that now can never be beaten because the circuit no longer exists: Pope, 124.51 mph in’39.

Back when motorcycles were more socially acceptable than they are today, the Archduke Wilhelm of Hapsburg raced Brufsups, once winning the Grand Prix of Baden on one. The supercharged and fully streamlined BS outfit known as Leaping Lena, property of Australia’s Alan Bruce, became the world’s fastest sidecar rig in 1932, Lena was claimed to be the first motorcycle ever to develop 100 bhp. I rode her and can believe this three-figure boast.

In a journalistic capacity, I also both drove and rode as passenger in the first of George Brough’s two experimental banking sidecar jobs. This one, based on a Fred Dixon design that had won him the 1923 Isle of Man sidecar TT, involved the bodily raising and lowering of the sidecar by a long lever known to its intimates as the “asparagus;” on right-hand turns gravity had to be overcome, on left-handers it helped the passenger/operator. Brough’s second opus in a similar vein relieved the passenger of all exertion and effected the lift and drop motions by means of spring-loaded plungers engaging with an open-ended helix formed on the inner face of the sidecar wheel. Neither of these attempts to snub centrifugal force got off the ground productionwise.

The same fate bedeviled Brough’s several essays in radically nonconformist cycle design. These have the makings of a lengthy story in themselves...the V-4 of 1927 with its side valves in the crotch of the banks (“As secret as a nest of nightingales,” vide Keats)...the 1928 straight Four, designed by Bert Le Vack in his position as development engineer at M.A.G. of Geneva (Bert was killed in a road accident before rear cylinder * seizure problems could be licked and this paragon of neatness and symmetry thereupon died, too)...the twin rearwheeled straight Four with an oversized (800-cc) Austin Seven engine, final drive shaft located between the back wheels, electric starting (this one was primarily for sidecar use but could safely be ridden solo and was taxed as a car under the British fiscal system)...the transverse V-twin of 1937, with its flathead AMC engine, car type clutch and gearbox... last and most sensational of all, the BS Dream, a 71by 63-mm transverse flat Four that in the words of C.F. Allen, a leading Brufsup historian, “could best be imagined as two flat Twins mounted one above the other and (he crankshafts geared together...”

If these flights of engineering fancy needed justification, it was supplied by the dumbfounded seekers they magnetized to the BS stand at successive London Motorcycle Shows. This, for a man with George Brough’s flair and appetite for publicity, was some compensation for the otherwise unrewarded effort he put into them. Meantime, while the idealist of Haydn Road was fretting for the millennium that never dawned, men made in the mould of hard-riding, tire-flaying Col. Lawrence could solace their souls with SS80s, SSlOOs, Alpines, 1 1 -50sthe steel magnificence of strength and speed. [o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

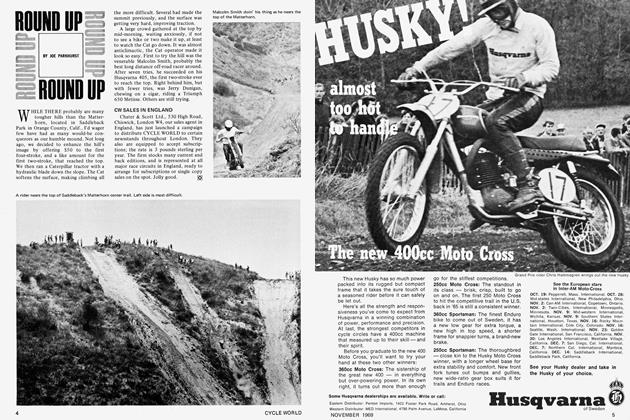

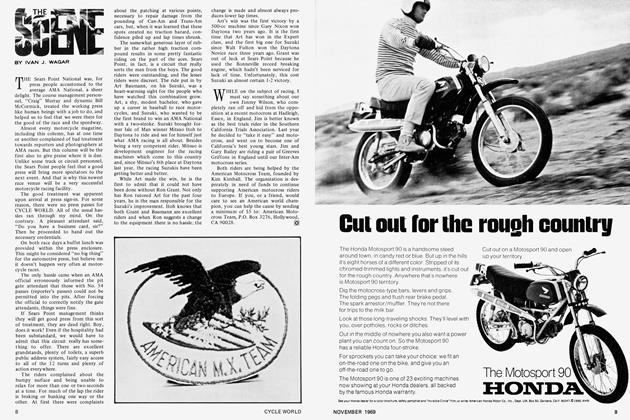

DepartmentsRound Up

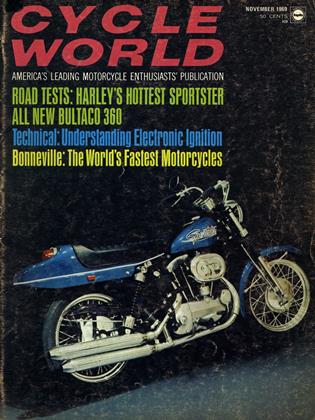

November 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

November 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1969 -

Special Feature

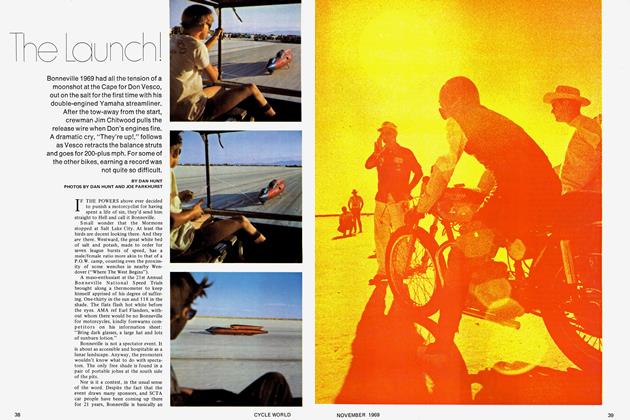

Special FeatureThe Launch!

November 1969 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

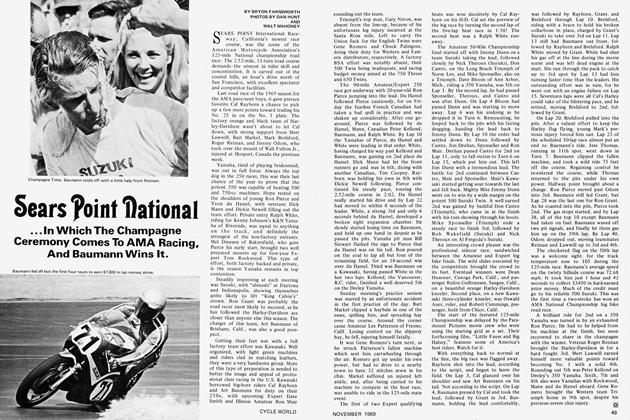

CompetitionSears Point National

November 1969 By Bryon Farnsworth