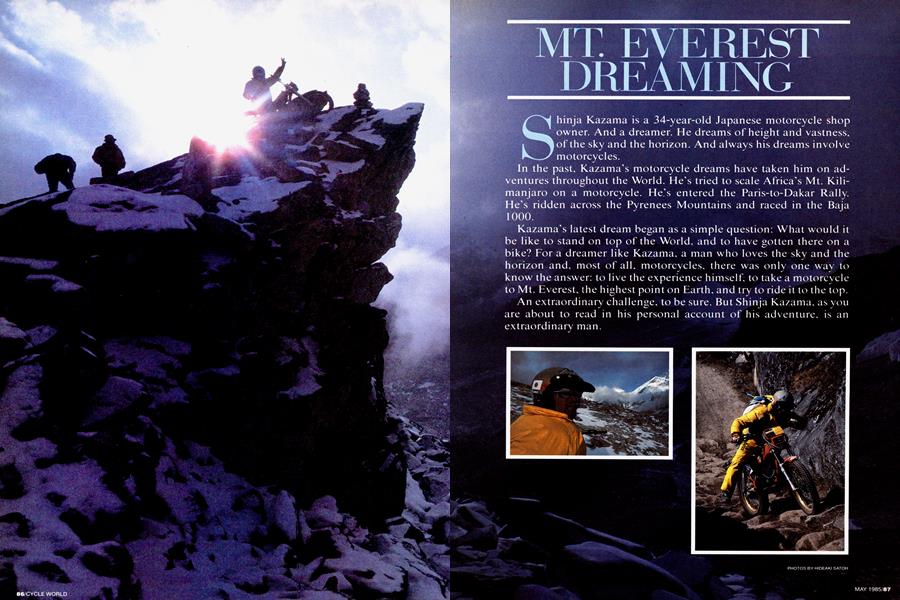

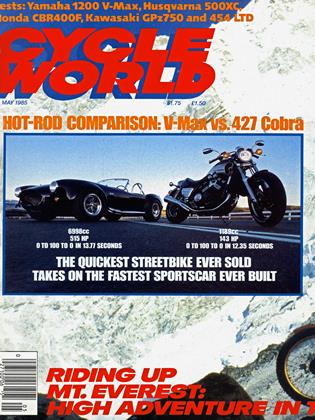

MT. EVEREST DREAMING

Shinja Kazama is a 34-year-old Japanese motorcycle shop owner. And a dreamer. He dreams of height and vastness, of the sky and the horizon. And always his dreams involve motorcycles.

In the past, Kazama's motorcycle dreams have taken him on adventures throughout the World. He's tried to scale Africa's Mt. Kilimanjaro on a motorcycle. He’s entered the Paris-to-Dakar Rally. He's ridden across the Pyrenees Mountains and raced in the Baja 1000.

Kazama's latest dream began as a simple question: What would it be like to stand on top of the World, and to have gotten there on a bike? For a dreamer like Kazama, a man who loves the sky and the horizon and, most of all, motorcycles, there was only one way to know the answer: to live the experience himself, to take a motorcycle to Mt. Everest, the highest point on Earth, and try to ride it to the top.

An extraordinary challenge, to be sure. But Shinja Kazama, as you are about to read in his personal account of his adventure, is an extraordinary man.

November 1:

Mt. Everest, 29,000 feet—five and a half miles—above sea level.

Sagarmatha, the Nepalese call it, the Abode of the White Gods. Piercing through the Himalayan range, Everest, crowned by a halo of drifting snow, stands proudly as the highest point on the roof of Earth.

Mt. Everest dreaming: I’m about to challenge the majesty of the mountain on a motorcycle.

An hour and a half by helicopter from Kathmandu, we land on the hill ofSyangboche.

The members of our expedition: Setsu Amamiya, 49, my partner in Yeti Associates; Nobumi Suzuki, 31, a mountaineer who reached the summit of Mt. Everest in 1983; Hideaki Satoh, 40, freelance photographer; Emi Furuya, 30, Swissair flight attendant; Pempa Lama, 31, local herder; Hangpa, 36, Sherpa climber.

November 2:

At Namche Bazar, elevation I l ,300 feet. This small village is to be the base site of our Himalayan expedition. Flanking the village on either side are the peaks of Mt. Thamserku visible to the east, and Mt. Kongderi to the west, two towers 22,330 feet and 19,300 feet respectively, piercing the blue sky.

In this village, which rests in a niche amidst the tall mountains, we hire seven porters and seven yaks. The yaks are domesticated bison native to these high altitudes. Each capable of carrying a load of about 130 pounds, they’re an essential means of transportation in the hazardous mountain terrain.

November 3:

Finally set for departure. For the past few days, we've been blessed with continuing fine, clear weather. We set the carburetion on our Honda TLR230s for the 1 1,000-foot-plus altitude. The engines run well.

Straight ahead, we see in panorama the peaks of Ama Dablam (22,500 feet), Lhotse (27,600 feet) and the pyramidal form of the White Goddess herself, blowing pillars of snow into the heaven above. That’s where we’re headed for. As I think of the trek that awaits us, I feel my heart tense in renewed determination.

The trail winds off dynamically along the ridge. It’s no more than a mere 12 inches wide at some of the tighter spots, and only about 6 feet even at the widest. Over the side, it’s a straight drop down, all the way to the bottom where the Dudh Koshi River flows like a thin strand of silk.

Not much chance to enjoy the panorama anymore. The trail gets more and more arduous as we push on. Simply put, it’s a series of stone staircases and sharp zigzags across the steep incline. Even clearing what look to be easy obstacles turns out to be much more trying than I ever expected.

Three hours out of Namche, we halt at Puniçi Trunga. and decide to continue wi'th one bike solo. There are more tr4kkers on the trail than we've expe~d. That's one consider ation. But my partner Amamiya has already had a close call with the ddge's edge. and the trail ahead is bound to be increasingly more demanding.

Nearing dusk around 5:30 p.m., we reach Thyangboche (13,100 feet). We're all invigorated by a full day of heavy climbing.

November 4:

Our real expedition is still a long way further up. beyond the Base Cami, near Gorak Shep.

Because the terrain in this area is •unridable, even for the agile TLR, the one remaining bike will be carried up on foot by the porters beyond Thyangboche until we reach Gorak Shep.

It's been some time since I last wore these climbing boots.

By 3:30 p.m.. we're in Pheriche. elevation 13,900 feet.

November 5:

We'll be staying in Pheriche for the day. At around 9 a.m., we start climb ing one of the eastern slopes. The ele vation at its peak is about l6~50O feet. We're doing this to get our bod ies conditioned for the higher alti tudes. We turn back below the 16,000-foot level. By then. Satoh. our photographer. is getting sick.

N'fount~n `~icknes~'. An C~agonizing headache, nausea and vomiting. I'm not feeling so well myself in the after noon. I spend the rest of the day in~ the tent with a fever and a headache.

November 6:

The conditioning climbs we took yesterday are doing me good, and I’m already enjoying the hike today.

Up here, the trail runs parallel to the Dudh Gosi River, which earlier on the trip we saw flowing far below us. We arrive at Lobuche, 16,200 feet above sea level, situated on the bank of this frozen river. We’ll be camping in some cold weather tonight. For the first time on this expedition, I’m planning on wearing my down underwear.

November 7:

Making for Gorak Shep.

The agony of mountain sickness bears down on us ruthlessly. Satoh still isn’t feeling any better. I consult with the two veteran mountaineers in our party, Amamiya and Suzuki, on whether we should reconsider our plans. For a while, we’re all pretty much in agreement that we ought to turn back to Pheriche. But then Satoh's condition starts improving, so we decide to stick with our original schedule.

Mountain sickness should not be taken lightly. Just a couple of days ago, the sickness turned out to be fatal for an American woman who came up trekking.

To make carrying the TLR easier, we strip the bike of its front and rear wheels, forks, muffler, fuel tank and seat. That pretty much leaves only the frame and the engine, weighing about 100 pounds. That way, the porters and the Sherpani (a Sherpa woman) can split the load on their backs.

Leaving Lobuche, we head for Gorak Shep (17,000 feet) and Karapatar ( 18,200 feet) for some more altitude-conditioning climbs. My legs are in worse condition than my head. We trudge on over ice and moraine. The moraine, glacier surfaces pocked by large chunks of rock, is one thing that they’ve all warned me about. But I find that it’s even worse than they told me. We continue forward over this inhospitable terrain.

We reach Gorak Shep. Base Camp is within sight from here. So too are the great columns of ice that make up the Western Glacier. One look at this shimmering wall and it’s easy to see why it takes mountain assault teams more than a week just to overcome this 1650-foot rise of ice.

The incline itself is incredibly steep. And, pressed in from both directions, the great mass of ice rises up, clamoring. Deep crevasses open wide, many of them with gaps of more than 300 feet. Even if we didn’t have to carry the bike, we’d never be able to get past this icefall within the limited time that our schedule allows.

Enough altitude training for the day, and we head back to Lobuche. By evening, the headache and the nausea are gone, and we’re all feeling a lot better.

November 8:

We're in Gorak Shep by noon. We learn that the name Gorak Shep means "The Crow's Burial Ground."

Just past noon. SnOW starts falling. The harsh Himalayan winter is here.

We hurriedly a'ssemble the hike. But working in the snow, the biting cold gets to our hands. All the rubber parts are stifl~ frozen. Work is slow. We have an especially hard time fit ting the carburetor. The high altitude is also slowing down this precise work.

The snow keeps falling.

At night, we join the~Sherpa and Sherpani. and head to the bati. This bati, or teahouse, is the last one en route to Everest.

Everybody's worried about the snow. It drifts in through a ventila tion hole in the bati roof. Our spirits are low as we watch these snow flakes. But a German trekker joins us. livening up the conversation. `~lt must be fantastic riding your bike in this beautiful wilderness," he says. with such an enthusiasm that it buoys our spirits.

That night. our tents are buried deep in SnOW.

November 9:

To Pumo Ri.

Wake up at 6 a.m. Outside the tent, the whole world glimmers in silver. There's snow clinging to the bike's tank and seat.

Damn!" I try brushing off the snow with my hand. Most of it has frozen into ice. We’re already a day behind schedule, and the way it looks, we’ve missed our last chance. But the weather turns out to be excellent; maybe the ice will melt.

We spend the morning looking for a good assault route. We check out the mountaineer's trail on the eastern side and the slope along the Chagri Glacier on the south. Both are obvi ously impossible inclines. Then Suzuki, who went to check the Base Camp conditions, comes back with some good news. "Just go straight up the gorge on the northern slope, and that ought to get you right on top of the mountain's shoulder."

After a light lunch, I begin the ascent.

Feeling all those eyes on my back, once I'm off, I can't turn back. I don't have a choice: I have to make it. Climbing up the gorge, I crash twice.

Thirty minutes up, I reach the "shoulder" that Suzuki was telling me about. The grade here is so steep that the front wheel keeps floating off the ground. I meet Satoh and Amamiya, who started up on foot an hour ahead of me.

The trail runs straight up the mid dle of the slope, all the way to the top. But considering the snow-covered trail condition, I choose a course a little more to the north.

Seventy percent up to the top, I find that there are two peaks instead of one. Dammit, which one's the summit? If I stop here, I'll lose mo mentum. But I don't have much of a choice except to stop and figure this one out quick. I find a stretch where the slope is a little more gradual, and I stop. I'm lost, not knowing what to do next. Then I see a party of climb ers on their descent from the summit. I get off the bike and patiently wait for them to come down.

I ask their Sherpa guide which one's the summit. He simply answers that they both are. Assured that they both are the peaks of Pumo Ri, it's only a matter now of deciding which one's the higher. The peak on the left seems farther off.

Dodging boulders and frozen patches of snow, I drive the TLR straight for the sky.

Ai it turns out, the peak that I reach is the southern column of Pumo Ri, elevation 23,435 feet. From here, I face the majesty of Ever est. I feel something kindling hot within me. This is a truly moving ex perience. I catch myself caressing the TLR's fuel tank.

Then I realize my dream has come true. I feel as if I've finally conquered the mountain. And even though the TLR and I are balanced on the Pumo Ri crest 5500 feet below Everest's fa mous peak, the feeling is the same as if I had set foot on the summit of Mt. Everest itself.

November 10:

Back at the Base Camp.

I know I can go no further. But I want to give it a try. I at least want to touch my front wheel on the edge of the icefall that leads to Everest's pinnacle.

I rev the TLR. It's a thousand feet more to the great white wall.

FOUr hou~s from departure, with the icefall agonizingly close, I can go no further. I turn back from the mountain.

November 16:

Return to Kathmandu.

November 24:

Homeward bound.

Epilogue:

Of course, I knew before I arrived at Everest that the TLR and I wouldn't make it all the way to the summit. There is, after all, a limit to the tires' gripping power. But I never lost faith in the motorcycle. Or my dream. The only reason I ventured this far, climbed this high on the mountain, was because I wanted to do it on a bike. In a way, the bike made me do it.

People ride motorcycles for differ ent reasons. If you have a thousand different motorcycle riders, you're bound to have a thousand different reasons why they ride. I can't really find any words that adequately de scribe my own fascination with mo torcycles. Not even the greatest poets or writers could possibly put these feelings into words.

Ofcourse, many people ask "Why?" It's as if they need to know everything just to have an easily un derstood answer. But more important in the special world of motorcycling is the question of "How?" To me, it is how you ride that makes the differ ence. And that is what makes the world of motorcycles all that much more valuable to me.

The ways that you can ride a mo torcycle are limitless. And so too, are there no limits to your dreams.

My bike is a ma~hine that produces my dreams. And when one dream sees realization, there's always an other one ready. So I'll keep on dreaming; until the day I die.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

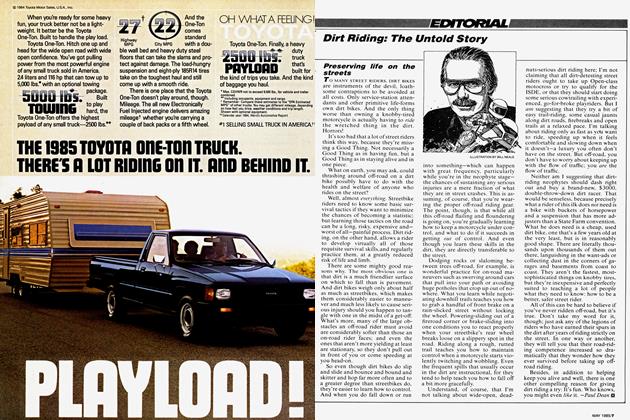

EditorialDirt Riding: the Untold Story

May 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupMotorcycle Leasing: the Next Alternative

May 1985 By David Edwards -

Features

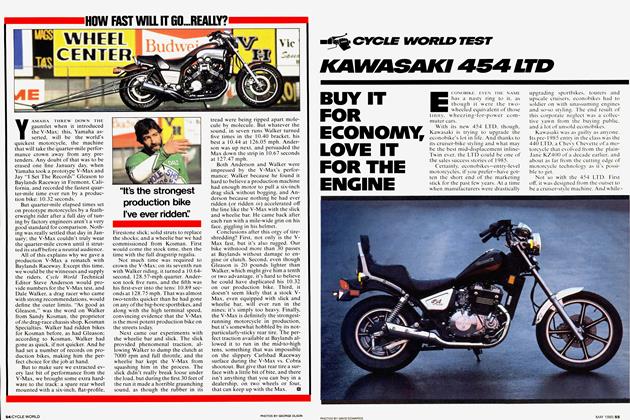

FeaturesHow Fast Will It Go...Really?

May 1985 -

Features

FeaturesA Legend In Its Own Time

May 1985 By Richard Simpson -

Departments

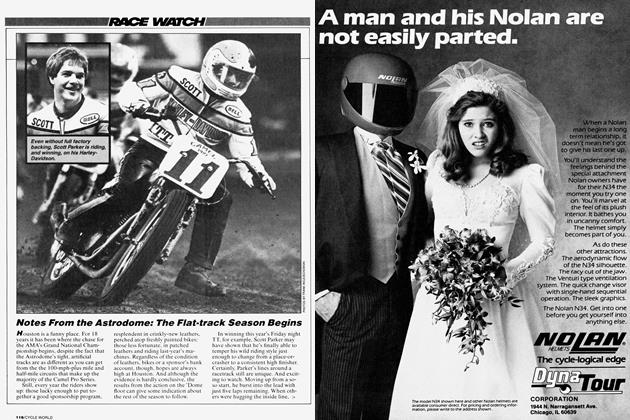

DepartmentsRace Watch

May 1985