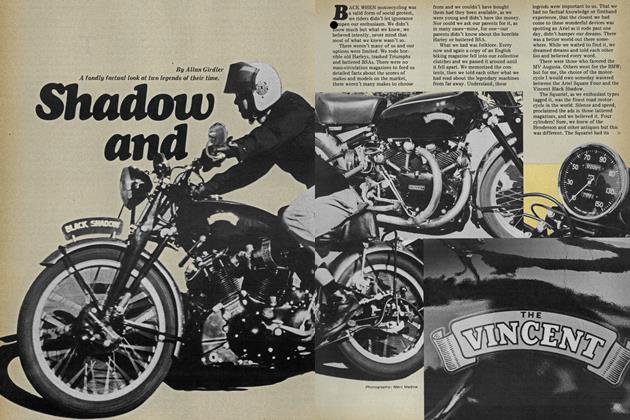

A LEGEND IN ITS OWN TIME

England's last great motorcycle benefits from a master-craftsman's touch

RICHARD SIMPSON

IT'S NOT EVERY DAY THAT SOMEone can reach back into history and reshape it to his liking. But in a small motorcycle shop in the fog-shrouded midlands of England, a man is doing just that. He's Les Williams, and his particular bit of altered history is the Triumph Trident, a motorcycle he lovingly remodels into what he has named the Triumph Legend.

Back in the last days of the British motorcycle industry, the Trident en sured that the sad remains of a once mighty manufacturing empire went out in a blaze of glory, rather than merely fading away in the light of a bright sun rising in the East. This three-cylinder 750, marketed as both the Triumph Trident and the BSA Rocket 3, was the last attempt by Britain to launch a motorcycle into head-to-head competition with the rest of the world. The racing record of this machine, in both BSA and Triumph versions, showed that the British could still take on the world and win, even if those successes were on racetracks, not showroom floors.

Technically, the Triple was one of the most significant machines to emerge from the Sixties. Its 750cc engine produced 58 bhp. an impressive figure back in 1968, and its three-cylinder configuration provided a vision of the future of motorcycling, a future where cylinder multiplication, high complexity and even higher performance would become the standard. Nonetheless, the Trident still had its roots firmly entrenched in the past. Its pushrod motor often leaked oil as badly as any of its twin-cylinder predecessors, and it even retained vertically split crankcases in an era when horizontally split engines were fast becoming prevalent. In truth, however, the engine had been “designed,” if that’s the word, by simply adding an extra cylinder to the Triumph Twin engine that had been around since 1937, although the Triple was later to grow a five-speed gearbox and electric starting.

Despite its 30-year-old ancestory, the Trident/Rocket 3 soon made a name for itself, especially on the racetrack, where competition versions of the Triple trounced the opposition at almost every opportunity. But the tables were turned by the Japanese in the showrooms. Because while many riders would have killed for a streetlegal version of the racer, the standard Trident/Rocket 3 lacked the appeal of Japan’s first true superbikes— Kawasaki’s 500cc two-stroke Triple and Honda’s sophisticated 750 Four.

Les Williams was the person who was largely responsible for the continuing racing success of the Trident long after the BSA-Triumph group had been butchered on the floor of the Stock Exchange. One of Williams’ bikes even had a personality all its own. A production racer that used the standard T160V Trident frame, it was known to the public as Slippery Sam after an incident at the 1970 Bol d’Or race in France where the machine had wet-sumped badly, covering itself and its riders in oil. Sam went on to win the Isle of Man Production TT, arguably the hardest roadrace in the world, no fewer than five separate times.

Still, racing success was not showroom success. So with Triumph’s financial outlook growing more bleak by the moment, Williams set up shop on his own (LP Williams, Common Lane Industrial Estate, Kenilworth, Warwickshire, England CV8 2EF), and began producing a number of Slippery Sam replicas, which were fairly standard but carefully prepared T160V Tridents with racing bodywork. The Legend is essentially a further development of those racebike replicas, with the rough edges rounded off to make a thoroughly practical roadbike.

The 750cc engine produced 58 bhp, an impressive figure back in 1968, and the three-cylinder configuration provided a vision of the future of motorcycling.

Williams wants the Legend to be thought of as the bike the Trident could have been today had development continued. For this reason, the bike does not have high-compression pistons or radical camshafts. The engine is close to the normal state of tune, and the only power-boosting modifications are a little attention to the cylinder head and the fitting of an electronic ignition.

Having spent much of his working life with motorcycles, Williams has a strong dislike of noisy machines. Thus, the Legend is fitted with some very modern-looking silencers that make the machine as quiet as most contemporary European motorcycles. The styling has been refined, too, for gone is the traditional Trident look. Instead, the Legend is styled as a sports-roadster in the European mold, with the odd glance back at the past. The bulbous tank and highly polished Triumph engine are traditional Old English, while any similarity that the rear end of the machine bears to the latest Laverdas is purely intentional.

Without doubt, the combination is pleasing to the eye. but Williams would be sorely disappointed if his creations were only looked at; he also intends the Legend to be used for fast, long-distance road work. To that end, the footrests have been moved rearward and are now situated behind the engine. This allows them to be brought closer together, improving both ground clearance and rider co'mfort. The handlebars are almost flat, with a small amount of adjustment built in, and the single seat, although externally similar to that used on Slippery Sam, has a neat storage space under the hump.

The result is a not-quite-café-racer riding position, one in the best European sports-tourer tradition. At speeds above 50 mph. the rider's weight is supported by the windstream, and his body is braced by the rearset footrests and humped seat. This riding position contributes to the relaxed feeling of the bike, for while a standard Trident feels as though it just might shoot out from under you as the revs pass 4000 rpm at full throttle, the Legend carries its rider along with it.

In truth, though, the Legend lacks brute bottom-end power, although its absence is disguised by low gearing that allows a not-very-ambitious 120mph top speed. Although this doesn't do much for the fuel comsumption of what already is, by British standards, a very thirsty engine, it does reduce the need for frequent gearchanging in traffic. Williams says that when he was building racers he was never bothered about increasing maximum speed; the idea was to get the bikes lapping the circuit as quickly as possible, and this philosophy is carried over in the way that he sets up his roadbikes. The good power starts coming in around 4000 rpm, which is about 75 mph in top gear, and the vibration comes in 1000 rpm later, when the bike really tingles. Williams describes it as “power vibration,” and it feels quite pleasant in the short term, but gets increasingly irritating as the miles build up.

An aspect of the bike that has come in for heavy modification is the brakes. Williams uses fork legs similar to those fitted to the last Triumph Twins to come from Meriden, which means that the Legend carries double discs on the front wheel. These are gripped by twin Lockheed racing calipers, but, surprisingly, they don’t make the front end at all over-braked. A similar unit performs stopping duties at the rear, but is far more sensitive and can lock the rear wheel almost too easily.

The clutch is an eye-opener for those who expect a British biker to be able to crush golf balls with his left hand. On a Legend, the action is as light and sweet as that of any modern Japanese bike; and according to Williams, the secret has more to do with cable quality, routing and lubrication than with any serious modifications.

What emerges from all this is a bike that does a lot of things very well, but not one of them outstandingly. Straight-line performance is comparable to that of the latest 550600cc Japanese machines, and the bike doesn’t handle quite as well as a 900 SS Ducati, although the Legend’s Paioli shocks are better than the oversprung Girling struts that were fitted to the Trident as standard equipment. But the best motorcycles are always greater than the sum of their parts; and it is the way in which every aspect of the Legend complements all the others that makes the Legend such an outstanding package. For example, the good handling of the standard Trident was marred by poor ground clearance, with the footrests in particular grounding far too easily. The folding rearset pegs fitted to the Legend mean that you have to do something very silly indeed to deck anything solid, but they also make the bike very comfortable to' ride at medium and high speeds. The riding position matches the handling, really making the rider feel that he is in control. And the steering, aided by the short, flat handlebar, is confidence-inspiring, whether you are blasting down a bendy backroad or pottering along a narrow lane with gravel and organic waste products at every corner. The narrowness of both handlebar and footrests makes the bike feel smaller, lighter and easier to ride than a standard T160V Trident.

Ever since an article on the Legend appeared in the British magazine Classic Bike, Williams reports that demand has outstripped supply, with over 70 of the machines sold. Seven Legends have gone to America, and inquiries from Australia number about four a week. Williams even has given up some other aspects of his Triumph spares-and-repairs business to concentrate on turning standardbut-scruffy Tridents into living Legends in a bid to boost output from the batches of 10 per year that he initially planned to produce.

Williams has resisted the temptation to reduce demand by increasing prices, for he wants to see the Legend remain within the reach of ordinary bikers. The result of this policy is that Williams is unable to quote firm delivery dates. Thus, obtaining a Legend is like buying that other great British sports vehicle, the Morgan automobile: The customer must be prepared to put his name at the bottom of the list and await delivery in his turn. The price remains very competitive, currently just under $3500, or about the price of a new Yamaha FJ 1 100 in England. Sort of like buying a fully reconditioned Aston Martin for the price of a new Datsun.

For those few who have remained faithful to British motorcycles up to, or beyond, the bitter end, Williams has done what was thought impossible. The dream of a road-going Trident built to the same standards of those thunderous racing Triples has come true. The Legend lives on.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue