The Launch!

BY DAN HUNT

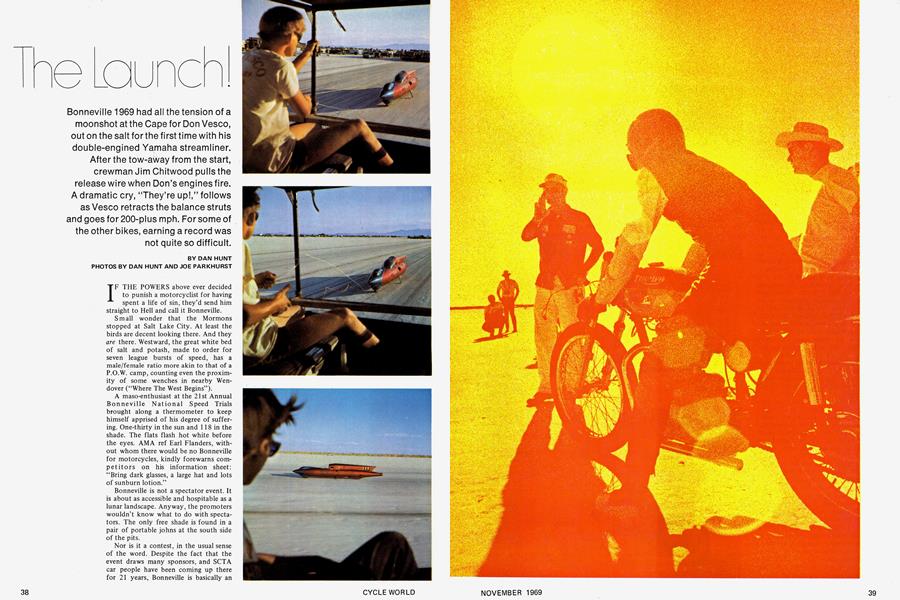

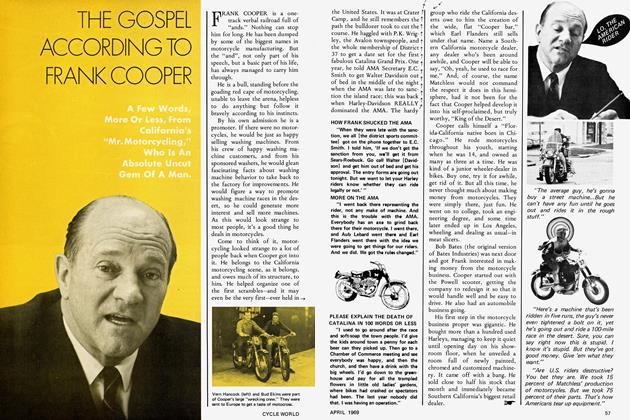

Bonneville 1969 had all the tension of a moonshot at the Cape for Don Vesco, out on the salt for the first time with his double-engined Yamaha streamliner. After the tow-away from the start, crewman Jim Chitwood pulls the release wire when Don’s engines fire. A dramatic cry, “They’re up!,” follows as Vesco retracts the balance struts and goes for 200-plus mph. For some of the other bikes, earning a record was not quite so difficult.

IF THE POWERS above ever decided to punish a motorcyclist for having spent a life of sin, they’d send him straight to Hell and call it Bonneville.

Small wonder that the Mormons stopped at Salt Lake City. At least the birds are decent looking there. And they are there. Westward, the great white bed of salt and potash, made to order for seven league bursts of speed, has a male/female ratio more akin to that of a P.O.W. camp, counting even the proximity of some wenches in nearby Wendover (“Where The West Begins”).

A maso-enthusiast at the 21st Annual Bonneville National Speed Trials brought along a thermometer to keep himself apprised of his degree of suffering. One-thirty in the sun and 118 in the shade. The flats flash hot white before the eyes. AMA ref Earl Flanders, without whom there would be no Bonneville for motorcycles, kindly forewarns competitors on his information sheet: “Bring dark glasses, a large hat and lots of sunburn lotion.”

Bonneville is not a spectator event. It is about as accessible and hospitable as a lunar landscape. Anyway, the promoters wouldn’t know what to do with spectators. The only free shade is found in a pair of portable johns at the south side of the pits.

Nor is it a contest, in the usual sense of the word. Despite the fact that the event draws many sponsors, and SCTA car people have been coming up there for 21 years, Bonneville is basically an assemblage of very sanitary amateurs. A contest implies opposition, which is to say, one guy bloodies another guy’s face. One wins, one loses. There may be a bit among the car people, but the bike people haven’t been there long enough. And it’s just too damn hot.

So, if you have a semblance of a legal mind, you switch to another class when you get blown off in the first one, unless you’re into the speed thing so deep that to meet your competition in any manner less than head on would be a case of lost honor. Fortunately there are enough of these red hots, usually regulars at the salt, to produce a few exciting moments, if the spectator can manage to unscramble the myriad classes with the aid of an entry sheet and a set of rules.

But, let’s get back to the legal mind way of non-competing. A classic example of the ploy occurred this year. A rider, originally entered in an unstreamlined class, taped a gas funnel to the fork crown of his machine. His bike looked like a refugee from the “Wizard of Oz:” Yet he was now ready to go cherry picking in a relatively unused, and perhaps less competitive, “partially streamlined” class. Had he failed in “PS,” he might have added another variation on the theme by welding a piece of scrap iron on his frame in a strategic place (extending the swinging arms for example), which would have made it a “modified” frame. Now he would be ready for an attempt on an “APS” record. If he still was blown off, he should have then removed the gas funnel. Then he runs for an “A” record. If no luck, he should cover the whole bike with a belly tank or facsimile, and run in “S” (wheels covered, fully streamlined) class. All these possibilities stem from “C” (stock frame) class (which also includes, besides stock frames, those frames approved for Class C AMA professional competition).

Add to these variations, the ones possible on the engine: C, stock engine running on gasoline (or not so “stock” yet conforming to AMA professional class C rules); AG, modified (usually bore or stroke) on gas; A, fuelers; and AB, fuel or gas powered supercharged engines.

Multiply the permutations by 16 displacement classes ranging from 50 to 3000 cc, and we now have an idea of what the “world-famous” Bonneville is all about for a large number of motorcycle competitors. There are no less than 320 classes available for erstwhile record holders!

Some of them are so improbable that you could take a clapped out rig up to the flats and run it through in reverse to easily claim a national speed record. (At which point, poor Earl Flanders, who has patiently and devotedly run the motorcycle part of the program since it began, would finally blow his cool.)

Meanwhile, we have 320 classes, and lots of open records to fill, right? So who can blame the legal mind.

And who can blame Embry & Bias singham and weird framed Honda for setting a national speed record (in Class A-C-SO) of 38.557 mph? Molehils as well as mountains are there for men to climb. Trouble is, it takes that Honda about five minutes for the run each way (yawn). The run qualifying the bike for the record attempt was made at 29.22 mph (yawn). It was the last machine to set out on qualifying that day, leaving Rick Vesco' s Offenhauser four-wheeler champing at the line wondering whether he'd beat the closing time deadline. The obvious happened, and at one point, several onlookers could have sworn that the bike had stopped on the course, optically deceived as that little snail-like microdot moved ever so imperceptibly away through the swarming whiteness. Qualifying closed with this five-minute absurdity and the waiting Offy stream liner didn't get to run that day. Hope fully the record for A-C-SO will remain unchallenged.

Meanwhile, Merci Dieu for the regu lars like Vesco, Richards, Leppan, Mur ray and Cook, Munro, Payne, etc., who can make even the car people sit up and take notice. Even though they may not be competing against one another, the high speeds they attain are enough opposition in themselves.

Fastest one-way motorcycle time of the meet was posted by Don Vesco, quite well known for his road racing activities. With a streamliner he designed himself and two standard 350-cc R3 Yamaha "Class C" road racing engines coupled together and running on gas, he was timed at 227-plus on one way of the record run, went slower the other way because of speed wobble problems and averaged out for an S-AG-700 rec ord of 214.062 mph. On the 227-mph run, he was revving 10,000 rpm in fourth gear with yet another cog to go. He figures that when he gets the han dling problems sorted out, he has a good look-in at beating the existing absolute land speed record for bikes, which stands at 245.6 67 mph, and is still held by Bob Leppan's Gyronaut X-l twoengine (Triumph 650s) streamliner. Ves co has good reason for believing that he can top 245. The combined output of Leppan's Triumphs was about 110 bhp, while the Vesco Yamahas each produce about 61 bhp at 9000 rpm. Coupled together to displace 700 cc, and throw ing away a few bhp for power trans rpission losses, the machine still has about 120 bhp on tap. Donny, who is the only member of the 200-mph Club to have surpassed that speed on both cars and bikes, is more than happy with his streamliner's first-time-out perfor mance.

Fastest bike record (two-way average) of the meet went to Gary Richards' single-engine 65 O-punched-to-75 0 Tri umph Twin, running on fuel. Jointly sponsored by CYCLE WORLD and Webco Inc., the Richards-Holtan stream liner set the S-A-750 record at 22 1.742. Richards and company had a tough row to hoe, and we only remember too well the heartbreak Gary suffered in previous years. Retractable skids are de riguer on two-wheeled "liners" now, but in 1965 and 1966 Gary didn't have them. So the long-wheelbase machine kept falling on its side before it could get enough speed to maintain balance. In 1967, Gary mounted skids, but they were too sharp and once again the machine ended up on its side after a successful first run of 196.71, to end hopes of establishing a record. Now, at last, CW has a modest piece of action on a 200-miler, thanks to the perseverance of Gary and crew.

Bob Leppan appeared this year with a formidable Triumph of Detroit crew, and the colorful designer of the Gyro naut X-l shell, Alex Tremulus, came along to garner information and offer advice to anyone needing it. (Tremulus would put a tail fin on anything that moved, if they let him. But he actually got a 3.5 mph increase for one unstreamlined rider, who, lacking a tail fin, was advised to stick his butt higher off the frame for better airflow).

Leppan brought the Gyronaut, powered by a single Trident, but it sat around most of the week, and burned a clutch on its record attempt. The major efforts of his crew were centered around a brace of more conventional Tridents. It was a wholesale grab at Triumph and BSA’s $25,000 purses for new records set at Bonneville. They were not unopposed in some of the classes in which they were competing, because Rusty Bradley and Virgil Davenport from Big D Cycle of Texas also wanted some of that cash. So records were broken, and went from camp to camp, as these two factions battled. It finally resolved with Davenport scoring two wins: 145.650 in PS-AG-750, 145.567 in APS-AG-750. Rusty’s Trident copped a third one for Big D: 148.323 in APS-C-750.

These are classes involving the use of road racing fairings, a fact which becomes more interesting when it is noted that the majority of the records scored in the Leppan camp on Tridents were in the unfaired classes. The Big D contingent is road racing oriented, while Leppan’s group is more closely associated with drag racing and Bonneville attempts.

Leppan analyzed the situation quite nicely: “We seem to have better engines than they do, but their (Big D’s) fairings are more slippery.”

All in all, Triumph 750s, the majority of them being three-cylinder, accounted for 16 new records set at Bonneville.

There were also a smattering of BSA Three entries, and at one point in the week, they held a few new records, which were subsequently wiped out by Triumphs-an engine design distinguished from BSA only by its name plate. This must have been a sickening displeasure for BSA, who had a sizable movie crew on the salt to film a promotional movie. If any conclusion may be drawn, it is that BSA’s racing blood has only been revived as of recently, while Triumph dealers have been competition oriented for many years without pause in American racing.

Drag racer Leo Payne stopped just short of becoming the first motorcyclist to score a 200-mph record on the salt without benefit of a full streamlining shell. His PS-A-3000 class Harley fueler ran a two-way record average of 196.512 mph. This was accomplished early in the week, and he was unable to go after the magic 200 due to a blowup on his last pass for the record.

Some of the Class C action was quite revelatory of present day trends. Don Vesco’s 350-cc Daytona Yamaha with fairing set an PS-C-350 record, 150.266 mph. Tony Murphy vied in the same class and finally got his Bridgestone to run 149 mph, not quite enough for a try at besting Vesco’s mark. The revealing part of the story is that the PS-C bike in the 750-cc displacement category ran only 147.723 mph.

It was a busy week, and the car people were looking a bit on edge as they felt the metamorphosis of Bonny from a car event into a bike event. Many holes were plugged in the AMA’s complex record book, so perhaps it is good that so many entrants went cherry picking. As those 320 records are answered for, one by one, subsequent attempts on them will become much more meaningful. [Q]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

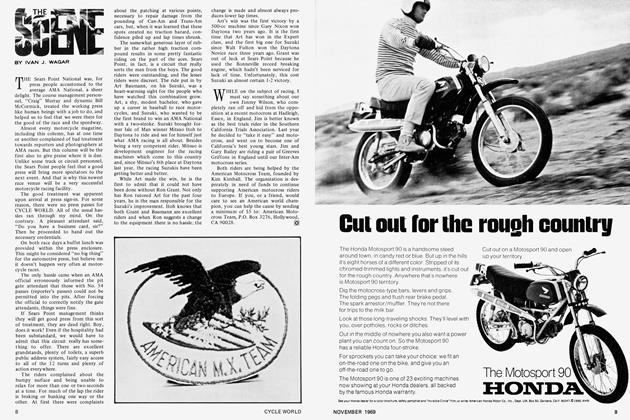

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

November 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1969 -

Features

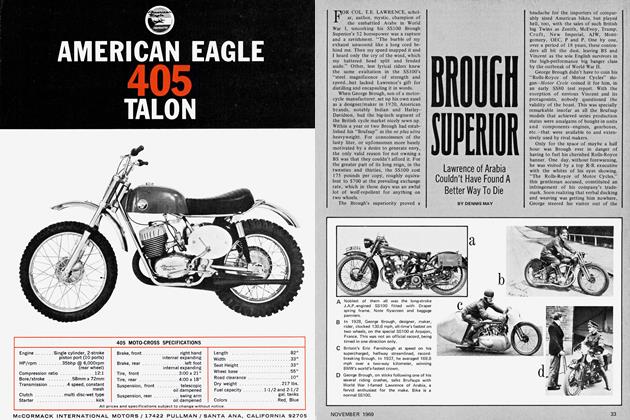

FeaturesBrough Superior

November 1969 By Dennis May -

Competition

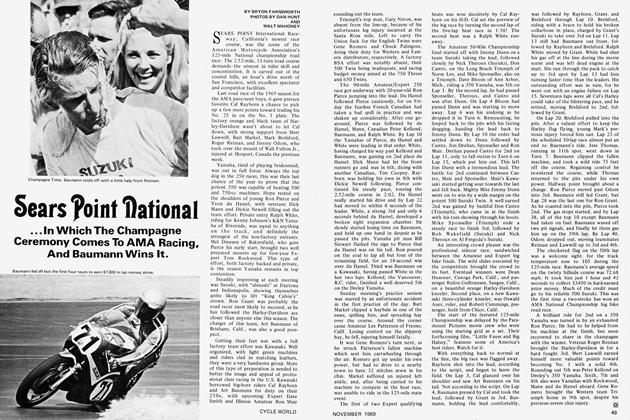

CompetitionSears Point National

November 1969 By Bryon Farnsworth