ERNST HENNE

A GENTLEMAN OF SPEED

He rode those BMWs to the Absoluten Motorrad Weltrekord....

DENNIS MAY

COMING EVENTS, in the antiproverbial way they often have, cast no shadows before them the day that Muehldorf, an obscure Bavarian township, staged a motley of motorcycle races in the spring of 1925. Nobody present, therefore, foresaw that one rider in particular in a lineup of regional hams would someday become an habitual breaker of the Absoluten Motorrad Weltrekord (world motorcycle speed record) and a two-time road racing champion of Germany.

At Muehldorf, about the only thing that distinguished E.J. Henne from the other no-accounts was his extraordinary machine, a Megola with a five-cylinder radial engine located in the front wheel. With no gearbox to bother with, Henne had his hands that much freer to deal with pilotage problems, which was all for the best. With all that unsprung weight up front, the zany Megola was as skittish as a ruptured fairy.

Henne himself, befitting his first name, Ernst, was a shy, serious, introverted fellow, 21 years of age, and with an un-Bavarian liking for cold milk in preference to beer. Muehldorf was the first race he ever contested and he didn’t win it. He had held a rider’s license since he was 15, and currently owned and ran a small Munich dealership for two locally built cycles, Megola and Mabeco.

Ernst learned fast, one of his first discoveries being that for racing one didn’t need five cylinders, and anyway the front wheel was the wrong place for them. Lesson two was that, if he were to make an international name for himself, as he was privately resolved to do, he would have to range farther afield than Muehldorf. So, late in 1925, he was to be found at Monza, the new track near Milan, Italy, astride more raceworthy iron, viz, a 350-cc Astra, again Munich built, but powered by a British ohv Blackburne engine.

As so often happens in storybooks and so seldom elsewhere, highups from a famous factory, on the qui vive for the rider talent, were on the Monza sidelines. Henne was on the top of his fast developing form that day and, in spite of stops to change plugs, placed 5th in the 350 event. Incidentally, the winner was the then youthful Tazio Nuvolari, destined to become his era’s (some would say, all-time’s) greatest grand prix car driver. The little Mantuan’s mount, a Bianchi, was the first bike ever to feature dohc.

After the racing was over, three visitors from Bayerische Motoren Werke, BMW for short, introduced themselves to Henne. Their proposition, stated by engine designer Dipl. Ing. R. Schleicher, was simple and to the point: Would Ernst be interested in joining factory employes Toni Bauhofer and Rudi Ecker on the BMW works team? Himself, Henne could retain his independence as long as he was prepared to wash Megola and Mabeco out of his hair and take up a BMW dealership.

Not surprisingly, Henne jumped at the deal, and was, as it developed, saved the trouble of jilting Megola because this firm folded under its own unsprung weight a few weeks later. Mabeco, in competition with BMW, Henne told an untearful goodbye.

And there began an association that was to rocket the quietly ambitious Ernst to the pinnacle of motorcycle fame: per ardua ad Astra ad BMW, to elongate the RAF’s famous motto slightly. From early in 1926 until his seventh and final Motorrad Weltrekord in November of 1937, his allegiance to the sign of the blue and white hotcross bun, BMW’s revered trademark, never was to waver.

Five years after his enlistment by BMW (intervening history will be detailed later) Henne donned his meteorcycling suit, and made his first and immediately successful bid for the title of world’s fastest rider. Spacemanlike, in leathers that fitted his lithe form like a body stocking, a faired-to-the-nape helmet, and a cone shaped appendage strapped to his posterior, he blasted over a kilometer stretch of the Munich-Ingoldstadt highway at 134.38 mph. Thumbs up for BMW and Germany, thumbs down for JAP (whose engines had powered the four previous world records) and Britain. Moreover, whereas JAP and the Anzani and Indian predecessors had gone all the way to the statutory 1000-cc limit, BMW voluntarily accepted a quarterliter handicap, using only 750 cc. This was in November, 1929.

Bayerische Motoren Werke naturally preferred to beat auslander rivals to merely excelling itself, and for awhile the British obliged. Englishman Joe Wright answered back 11 months later with a 137.01 dash along the Arpajon road, near Paris, on a supercharged OEC-JAP. Henne, again making 750 cc do a four-figure job, capped the Wright feat by a whisker at MunichIngoldstadt Then, settling the Anglo-German hassle for a two-year spell, Joe hit 150.5 at Carrigrohane, Ireland.

In round five, Henne, sampling a new course at Tat, Hungary, raised the bidding to 152.58 mph in 1932. No response came from Britain, so BMW, evidently figuring that a game of patience is better than no game at all, made three bids in a row. The last of these, in 1936, jacked the record to 168.64.

Meanwhile, as this string of unchallenged and therefore rather hollow BMW successes implied, UK motorcycle makers had gone cold on the game. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for a lone hand, courageous and virtually unsponsored independent, Eric Fernihough, an exhaust note with an English accent wouldn’t have been heard again on the Absoluten Weltrekord front. In 1937, at Gyon, Hungary, Ferni took a tiny but decisive shave off Henne’s 1936 times, riding a blown Brough-Superior-JAP he’d built and prepped himself. The following year, at the same course, he crashed and was killed while trying to improve his mark.

For Ernst Henne, world’s-fastest wholesaler, the end of the line was near. Six months after Femihough’s shim-thickness victory (at 169.8), Piero Tarrufi won the record for Italy with a supercharged water-cooled 500 Güera-170.5 mph. A little over a month later, the quiet Bavarian again hit the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn, scene of aU his meteorcycling triumphs since 1935, for the last time. The result was 173.29 mph. For a man now in his 42nd year, enough was enough.

MechanicaUy, the story of BMW’s long-time quest of the blue riband of speed has some interesting facets. The 750 engines used for the first five of Henne’s seven successful sorties were aU supercharged derivatives of street type clockwork, ah pushrodders. Although revved weU beyond the turnover for which they’d been designed, they were reliable in themselves in the short bursts the records involved, but likely to shear blower drives.

These 750 boxermotors (flat opposed Twins) came in four variants. The first, raced only in 1929, was square at 78 by 78 mm, giving 740 cc of displacement. Output was 5^ bhp at 6000 rpm, benefit of an eccentric vane ZoUer blower. The next-up unit, used by Ernst for his 151.53-mph mark in 1932, was way oversquare at 83 by 68 mm, equal to 735 cc, had an eccentric vane blower of BMW make, and developed up to 75 bhp, again at 6000. Editions three and four, run in 1934 and 1935, must have differed from their immediate forebears in respects that aren’t apparent from their outline specifications. Bore and stroke measurements were repeated, blowers were BMW-designed, power curves peaked at 6000 rpm, yet outputs were up to 90 bhp in 1934 and 102 bhp the following year. Changes were rung on fuels at various stages (methyl-alcohol was basic to all the brews, but nitromethane came into the formula in 1934, for instance), and this must have been significant.

When, after years of success with 750 cc, BMW gave this displacement question a second look, the firm’s racing people impudently decided the time had come to go down, not up, on engine size. That was in 1936. The switch then made to 500 cc was not, as could be assumed, quite so self denying, because the replacement engine was a fuel burning version of the special ohc line BMW had developed for road racing. With the dynamometer in a good mood, this welterweight boxermotor punched out 108 bhp at 8000 rpm.

Apart from windcheating attire and accessories worn by the rider, BMW’s early Weltrekord bikes were not, per se, streamlined in any advanced sense. The area outlined by the center frame, from the base of the fuel tank down to the engine/gearbox unit, was filled in by flat panels, the rear wheel was disced and the front fork girders were ovaled with taped-on fillers-and that was about it.

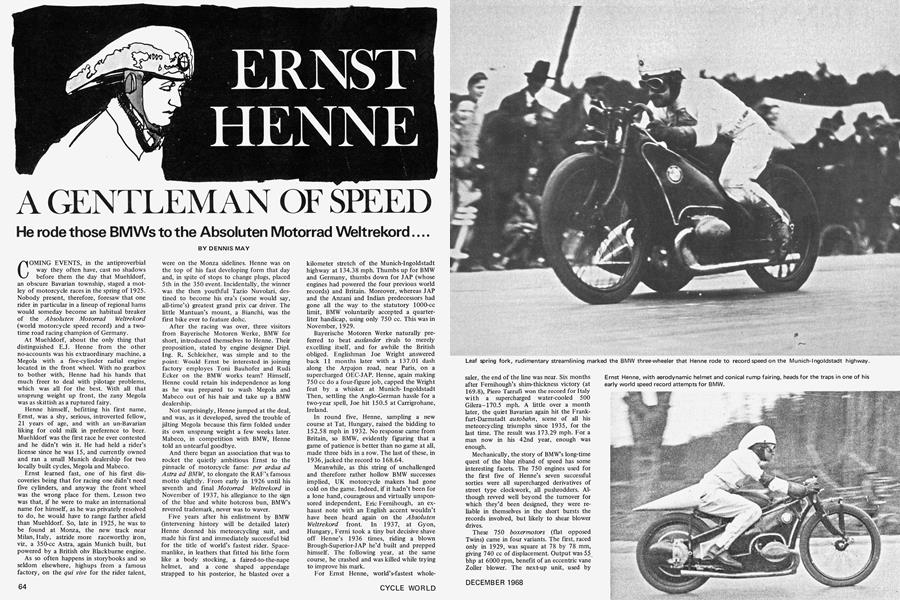

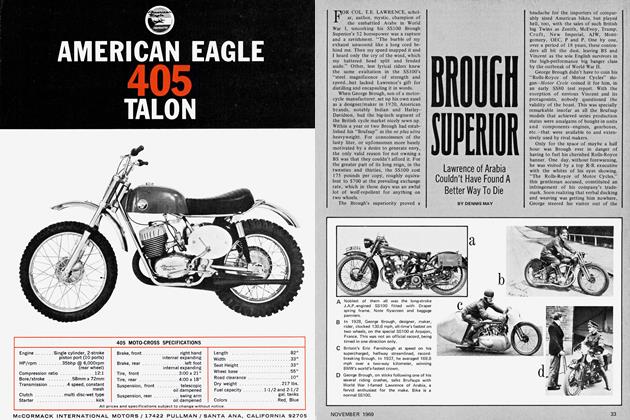

Later, Henne shoehorned himself into a full rennlimousin, as seen in accompanying photographs. This brought little, if any, reduction in the frontal area or total stature (that gazebo-high turret looks quaintly lofty by modern Bonneville standards), but must have cut overall drag a good deal. It was developed in the tunnel by one of the big German aviation firms-Messerschmidt. The first edition had a clean shaven back end, but, anon, the tail sprouted triple stabilizer fins. Up to 1936 inclusive, all of Henne’s record bikes, like their street counterparts, were fitted with trailing link front forks, each with a single leaf spring. Thereafter a telescopic fork was adopted. It is doubtful whether even the 1937 record 500 carried rear suspension. With the whole machine clad in aluminum lingerie, it could not be determined one way or the other.

Although Henne was chiefly famous as a recordman, his against-the-clock exploits occupied an insignificant fraction of the time he spent twisting BMW grips between 1926 and 1937. Inaction was anathema to his industrious, striving nature, and BMW obligingly kept him as busy as a big end. In speedsport, apart from the Absoluten thing, he was talented rather than great, winning many races and hülclimbs by sheer determination and refusal to be beaten, more than blinding brilliance. The two German championships mentioned earlier might seem to conflict with this assessment of him, but the competition he bested wasn’t always all that hot. He was credited with a total of 76 records, 69 of which (if his seven world beating sprints are deducted) must have been set in climbs and circuit races.

In these fields, of course, BMW concentrated mainly on the 500 class. As far as handling qualities were concerned, BMW was, and continued to be, a four letter word. Bedeviled by oversteer, the bikes would hang their tails out and kind of servo themselves into an exaggerated angle of layover when thrust into corners with power on. The art therefore-developed to its pinnacle by Georg Meier when he won the Senior TT in 1939—was to use every last ounce of the machine’s superior steam for acceleration out of turns and top speed on the straights, then prudently back off for the turns themselves.

Ernst Henne practiced this knack to good effect on the pushrodders he was racing in the 1920s and 1930s, and so did his teammates, such as Karl Gall (who was to die while training for the 1939 TT), Rudi Ecker and Hans Soenius. Significantly, BMW passed up the TT until the advent of the ohc racer in 1937 relieved the Munich riders of the necessity of wildfowling on corners.

Perusal of Ernst’s success statistics recalls that the Targa Florio, in Sicily, one of the oldest, most famous and grueling of car classics, at one time included a cycle class. Henne won it in 1928. Other happy hunting grounds of his were the old (pre-Nurburgring) Eifel Rennen, the Wildpark Rennen at Karlsruhe, the Solitude races at Stuttgart, and the famed Freiburg hillclimb. Ever versatile, he represented BMW in the Silver Vase division of the International Six Days’ Trial on several occasions, both solo and sidecar, winning six gold medals.

The twoand four-wheel chapters of the Ernst Henne story overlap by four years, and the latter, although arguably ungermaine to this portrait of a rider, cover a phase of his life that is too important to ignore. His introduction to racing cars came about this way:

In 1933, on the threshold of a grand prix epoch that was to produce all-time’s most powerful and hardest to handle road racing cars, the Mercedes firm had a problem. The difficulty was to find drivers capable of keeping the new breed of bombshells on the track and out of the treetops. With one mind, Mercedes and its only serious rival, Auto Union, looked to motorcycle riders to fill some of the impending vacancies. Auto Union hired Bernd Rosemeyer (and never made a better choice, though an AU was to kill him). Mercedes saw possibilities in the older, more level-headed Ernst J. Henne.

On the principle of having him walk before he ran, Mercedes bought, late in 1933, a current type grand prix Alfa Romeo and turned him loose on it. He quickly got the hang of the unfamiliar karate and, as soon as the prototype Mercedes racers were completed, early in 1934, was given trials on it at the Nurburgring. Unfortunately for Ernst, the German car was a different breed from the Alfa. The Mercedes was not only lighter, more powerful and with handling properties all its own, but also frighteningly “tender” in its throttle response. This was due to a gasworks arrangement that (designedly) brought the blower in, wham, somewhere in the midrange of accelerator travel, rather than blowing uniformly from idle on up. This was okay as long as the car was pointing straight when it happened, but in a turn ...Quo Vadis?

Well, it happened in a turn, just once in Henne’s experience, and the first thing he knew-or would have known if he’d been conscious on landing, which he wasn’t-was that he was floating face downward in a trackside pond. The Nurburgring lap being 14 miles around, and the area thinly populated because the circuit was on private hire to Mercedes that day, it was just a matter of luck that a local farmer chanced to be within rescuing range. Though thus saved from drowning, Ernst suffered a fractured skull and several broken ribs, having ricocheted off something solid on his way into the water.

He made a fast recovery, thanks to his customary physical fitness, and as he wasn’t the only Kadet who finished his tryout under perfect lack of control, Mercedes booked him for racing duties. He drove that firm’s racing cars in three 1934 events, at Monza, Brno and Pescara, but scored no wins or monied places and never quite lived up to his masters’ expectations. At the end of the season, perhaps figuring that with a Weltrekord background like his, his forte really lay in a straight-line action against the clock, he was assigned to a kilometer records job at Tat, where a couple of years ear her he’d taken Joe Wright’s marbles away. On a familiarization run, before actually attempting records, the streamlined top blew off the Mercedes at 160 mph, converting the car from rennlimousin to skyview form in a lot less time than it takes to tell. Veteran Mercedes driver Rudi Caracciola, who was among those present, then took over and broke the slated records.

“I left the Mercedes-Benz team at the end of 1934,” says Ernst, “by mutual, friendly agreement.”

Although never on the BMW payroll, which he’d no wish to be, his relations with the firm were always close and cordial, and no doubt the fact that Munich was their common hometown helped keep the friendship in good repair. Anon, his BMW franchise was widened to include cars as well as motorcycles. Henne’s lack of success as a grand prix driver did not blind those in authority at the Werke to his genuine talent as a car handler, and from 1935 until the outbreak of World War II he was never short of competition drives in the latest and most potent BMW sports cars. With the then hard to beat Model 328 he won his class in the 1935 Eifel Rennen, turning fastest time irrespective of engine size, later won the sports car Bucharest Grand Prix, and made fastest time in the Grenzlandring races in Belgium.

Past injuries, notably the beating he’d taken in his Nurburgring crash, kept him out of active war service, and he and his well equipped workshops switched to vehicle maintenance during World War II. In 1949, at which time BMW wasn’t even within sight of resuming production of either cars or bikes, Mercedes offered him the regional agency for its passenger vehicles and trucks and he took it, never to look back. Today, Ernst J. Henne divides his time between honorary activities in local politics and the direction of an automobile business which comprises three separate establishments and employs about 500 people. Deservedly, he is a man who has fallen on good times. Incidentally, one branch of Auto Henne, to give it its proper title, engulfs the site of the one-horse Megola and Mabeco dealership Ernst founded 44 years ago. His only son has a managerial position at Auto Henne.

At 64, Ernst isn’t too old to savor his first love, motorcycling. His choice mount, as could be expected, is a BMW. “I enjoy it best on forest and field paths,” he smiles.

How does he view the modern counterparts of the machines he gunned down the autobahnen in distant yesteryears in pursuit of the Absoluten Motorrad Weltrekord? His view is with little enthusiasm, mainly because of their ever more tenuous relationship to street machines. Back then, he allows, the lessons learned from record breaking and racing could and did make a direct contribution to the development of the bikes that everyday citizens ride, but not now.

On the other hand, improving the breed isn’t as pressing a need as it was when anything as improbable as a five-cylinder radial engine was likely to turn up anywhere as unlikely as in the front wheel. [Q]