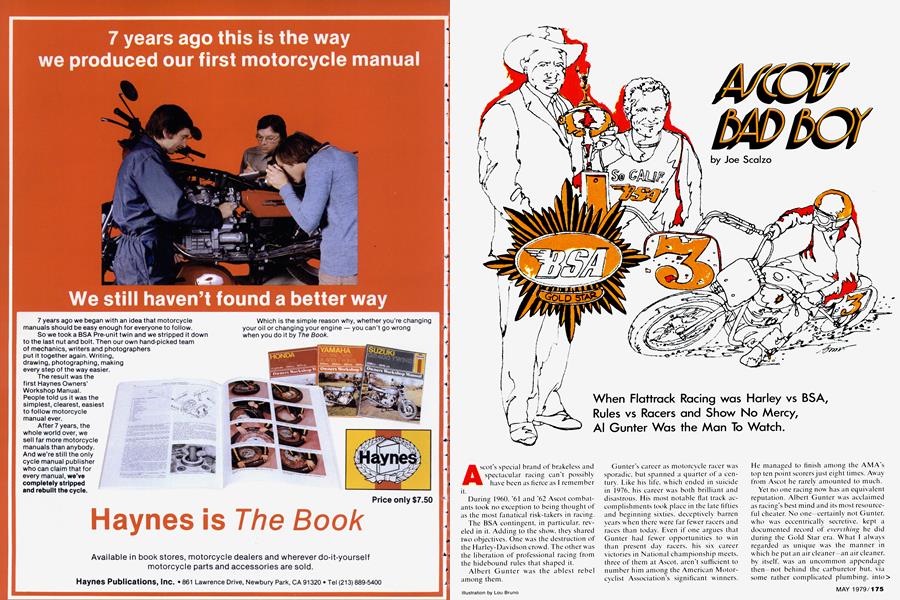

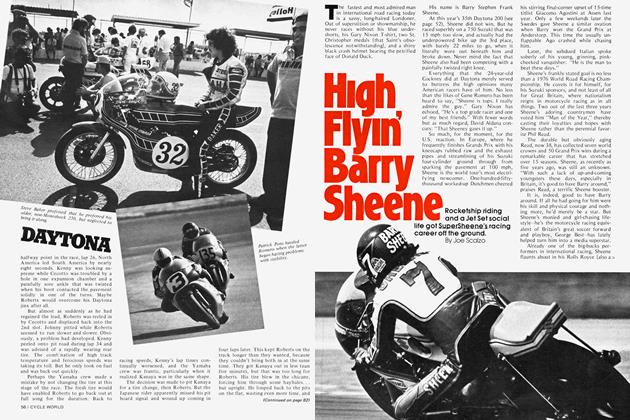

ASCOT'S BAD BOY

Joe Scalzo

When Flattrack Racing was Harley vs BSA, Rules vs Racers and Show No Mercy, Al Gunter Was the Man To Watch.

Ascot's special brand of brakeless and spectacular racing can't possibly have been as fierce as I remember it.

During 1960. '61 and ’62 Ascot combatants took no exception to being thought of as the most fanatical risk-takers in racing.

The BSA contingent, in particular, reveled in it. Adding to the show, they shared two objectives. One was the destruction of the Harley-Davidson crowd. The other was the liberation of professional racing from the hidebound rules that shaped it.

Albert Gunter was the ablest rebel among them. Gunter’s career as motorcycle racer was sporadic, but spanned a quarter of a century. Like his life, which ended in suicide in 1976. his career was both brilliant and disastrous. His most notable flat track accomplishments took place in the late fifties and beginning sixties, deceptively barren years when there were far fewer racers and races than today. Even if one argues that Gunter had fewer opportunities to win than present day racers, his six career victories in National championship meets, three of them at Ascot, aren’t sufficient to number him among the American Motorcyclist Association's significant winners. He managed to finish among the AMA’s top ten point scorers just eight times. Away from Ascot he rarely amounted to much.

Yet no one racing now has an equivalent reputation. Albert Gunter was acclaimed as racing’s best mind and its most resourceful cheater. No one certainly not Gunter, who was eccentrically secretive, kept a documented record of everything he did during the Gold Star era. What 1 always regarded as unique was the manner in which he put an air cleaner—an air cleaner, by itself, was an uncommon appendage then not behind the carburetor but, via some rather complicated plumbing, into> the rear fender. Not that I fully comprehended why Gunter put it there. Because Gunter did it, it was important. That was the convention at the time.

Gunter also appropriated credit for inventing what surely is the most identifiable piece of fiat track apparel next to the skid shoe the full-coverage crash helmet. I saw Gunter majestically w heel to Ascot’s starting line wearing the unusual hat one typically freezing Friday night in 1963, amidst a surprised reaction from the crowd as it obeyed the urging of the startled announcer, Roxy Rockwood, to “Get a look at the helmet worn by No. 3, AÍ Gunter!”

It even had a radio inside. Work on it as he might, Gunter was unable to overcome the problem of squelch, and the two-way radio in motorcycle racing became one of his lesser brainstorms, although it is still too early to dismiss it as a failure. Someone may yet do something with the concept. Another of Gunter’s apparent failures, the disc brake for road racing, eventually proved out, almost a dozen seasons after Gunter had the first discs on a Gold Star. Gunter procrastinated and vacillated and never followed through on developing the brakes. Others had to.

How Gunter, who is supposed to have won the first National on one, either at Sturgis, South Dakota, in 1954, or St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1955, came by his loyalty to the Birmingham Small Arms Ltd.’s Gold Star model, and what bred his aversion toward Triumph and especially HarleyDavidson, was a question I never heard answered. Loyalty to a chosen marque is incomprehensible in dirt track racing anymore because the one marque is HarleyDavidson.

The Gold Star did suit Gunter, though. Triumph, after all. lacked the expertise, or the will, or the budget, or the riders to wán National races. Before Gary Nixon took two in 1963, only six Nationals in nine years had been won by Triumphs. And Harley-Davidson most emphatically didn't have the technology to combat the trim, race-ready Gold Stars. The KR models from America’s only motorcycle manufacturer remained such antiques that some of Bart Markel's best engines in the middle sixties actually had “1953,” the date they’d been built, stamped on the crankcases. Everything on the factory bikes was oversized and crude, but centrally their ungainly flathead motors. How7 absurd, how laughable, were the bulbous KRs!

All the splendid things ever did was win and win. From 1954 to 1963, they won 91 out of 123 National meets. Not until 1963 and Dick Mann, who was a particular friend of Gunter’s, did anyone but a Harley-Davidson loyalist get to be champion of the U.S.

Mann and Gunter, along with Neil Keen, who was another influential constituent of the BSA Wrecking Crew, all commited apostasy during one HarleyDavidson-dominated year or another, briefly renouncing Birmingham for Milwaukee. They were as conspicuously unsuccessful at this as Joe Leonard, a threetime American champion, was when he temporarily went to Triumph after becoming disenchanted with Harley-Davidson's factory team.

Factory team is a term that is dangerous because it evokes 1979 images of team riders outfitted in matching leathers, reclining in easy chairs while skilled, uniformed tuners sweat over preparation of the race bikes, each factory racer guaranteed no part of such hardship, just as he is guaranteed all prize money, bonuses and a monthly salary. In Leonard’s day a HarleyDavidson factory racer often was his own tuner, earned no salary, and got little more than a KR model and the spare parts it took to continue racing it. Bart Markel, who won more Nationals than any other champion, frequently had to pay for his own tires.

Penurious as Harley-Davidson was, its generosity and the attention it paid its racers was positively overwhelming compared to BSA, whose U.S. importers’ lack of support and disinterest in the exploits of Gunter, Mann, Keen and the few others rebellious and stubborn enough to war with Harley-Davidson was at moments comical. A story, perhaps apocryphal, tells how Mann, a couple of days after he and Sammy Tanner pasted Milwaukee and gave BSA an outrageous one—two finish at the vaunted mile track of Springfield, lllinois, blew up his engine at some half-mile race in Kansas. He telephoned BSA’s west coast distributor expecting replacement parts to be air-freighted in. But the sly response was that because the engine he had broken in Kansas was undoubtedly the same one he had raced at Springfield, hé had surely done the original damage to it there. And since Illinois was geographically closer to the east coast then the west, Mann must call BSA's east coast headquarters if he expected help (the east coast subsequently said no. too).

continued on page l84

continued from page 178

Whenever this sort of thing happenedtoo frequently, Harley-Davidson was able to tempt BSA's most menacing campaigners to its camp: Mann in 1958, the garrulous Keen in 1962. and I can't recall the year the team got Gunter. For various reasons, all three promptly quit and got back on Gold Stars again, and both of Gunter’s compatriots returned their unwanted Harley-Davidsons. What Albert Gunter did with his, though, was quintessential—and darkly comic—Albert Gunter. He sold it.

A sharecropper's son who hitch-hiked away from his father's Louisiana shack at 14, and had been on his own ever since. Gunter experienced his most statistically satisfying, but gallingly frustrating, season as a regular on the 1957 Grand National tour. It began with his great run at the season title. It was highlighted by his scoring a totally incomprehensible victory at the TT steeplechase at Peoria without knowing how to steeplechase. But i£ finished with Gunter still seven miserable points shy of displacing Harley-Davidson.

Then there were the rules. It’s safe to say AÍ Gunter didn't like rules. Sometimes it’s ' easy to see w'hy.

One of the chief technical inspectors for the American Motorcyclist (nee Motorcycle) Association in California was Earl Flanders, a likable man who nonetheless pursued rule enforcement with all the zeal of the obsessed police inspector out of Les Miserables. Here is a remarkable example. In the rulebook was an incomprehensible statute proclaiming it a foul to shift gear for a corner and use engine compression to; check speed. So Flanders and his equally driven lieutenants once spent an afternoon under a baking sun on the roof of the old Sacramento fairgrounds with fieldglasses trying to focus on the faraway feet of racers (whose speeding, slewing cycles not only were separated from the rooftop by a distance of almost a mile, but by dust, smoke and traffic). They hoped to catch them making criminal dabs at gearshift levers. The grotesque strategy failed. All Flanders caught was sunburn. “We couldn’t see a damn thing,” he recalls.

All of them were fortunate not to have» tumbled down off the roof trying.

Later the unenforceable gear-shifting statute was taken off the books and Flanders returned to his unending pursuit of Ascot's Gold Stars, always rumored to be illegal. So they were—defiantly so. When Gunter and his co-revolutionaries weren’t attempting to sneak past Flanders with a set of lightweight aluminum forks, they were trying other things. Anything to fool Earl. Gunter tricked Flanders the most £>ften but also was apprehended in the act, and occasionally had his illicit Gold Star grounded for the night, the most often, too. Caught, he faithfully erupted with displeasure loud as it was profane. Nothing discouraged Gunter from trying it all again, or fighting back in any way he could.

' One year at Tulare the machines of the top three finishers, one of whom was Gunter, were impounded for engine inspection. Something about enlarged cylinder bores.

I have it on good authority that before Gunter would allow his engine to be opened up and any eyes but his own to £robe its polished, finely machined innards. he telephoned (collect) the residence of the executive director in Columbus, Ohio, demanding that the outrage at Tulare be halted. It was midnight in .California, meaning it was three o’clock in the morning in Ohio, but any satisfaction Gunter took from rousing the most important member of the AMA management "(who gave Gunter a piece of his mind) from a sound sleep, was spoiled by the director’s refusal to heed Gunter’s orders. The inspection continued, the inspectors twisting off bolts, Gunter cursing. Just as the cylinder head came free, Gunter made a lunge and covered the exposed piston with a rag. Nobody was permitted so much as a blink at its shiny, domed top. The "ruckus he raised notwithstanding, Gunter's engine proved to be legal after all. The disappointment was total.

Flanders remembers Gunter kindly. “He and the others became pioneers in getting the liberal equipment rules that we have todav. I respected Albert, and I think ■he secretly liked me. He really w'as a rebel.” And Flanders recalls all of the Gold Star era nostalgically.

Gunter's wasn’t there to be part of it. because its owner was either at the beginning or nearing the end of another of his futile bouts at retirement, but all of Ascot’s Gold Stars, properly enough, received an appreciative send-off in one of their last appearances. It happened in 1969, the year of the questionable change in the AMA’s engine formula that doomed both the Gold Stars and their enduring enemies, the KR Harley-Davidsons. An instant before the Friday night pack dropped clutches and everyone went roaring and grappling into a last, crowning, there-isno-Saturday extravaganza, over the RA. came a ringing, poignant “Farewell to the BSA Gold Stars!” from the perceptive Announcer, Roxy Rockwood.

Now entering his second decade of broadcasting motorcycle races, and still at the top of his form, Rockwood had a wonderful feel and passion for the early Ascot races. Sometimes I believed he was as responsible for the tensely serious Friday night atmosphere as Gunter and the rest of the BSA Wrecking Crew (whom Rockwood named) were.

It came as a towering surprise to me. then, when I first became acquainted with Albert, to discover that he had a colossal dislike of Rockwood. He found Rockwood’s weekly dosages of Ascot statistics and lore irrelevant and boring. Rockwood’s doggedness in pursuing, and obvious pleasure in relaying over the P.A., the latest gossip from the pits was. to Gunter, not informative but unrestrained nosiness—a disquieting and logical extension of Rockwood’s sinister workaday occupation as policeman. That was the source of the problem. Policemen always came first on the formidable list of things Gunter despised. Quite often the most innocuous remark the well-intended Rockwood made was enough to set him off.

The Friday night following the indelible Sunday afternoon at Lincoln. Illinois, in 1962, where a violent crash bludgeoned Carroll Resweber into premature retirement and killed a popular Louisiana veteran named Jack Ghoulson, Rockwood requested that the Ascot grandstands rise for a moment’s respectful silence for Ghoulson. Gunter flew into a rage about it, a regular tirade. Using logic that was as difficult for me to comprehend then as it is now. he expressed the opinion that Rockwood was desecrating the memory of Ghoulson, one of his heroes.

Now' that I knew Gunter a little better. I was as aware of his awful problem as everyone else who w'as familiar with him was—he w'as a dedicated and profound misanthrope. Perhaps the most self-revealing remark he ever made was about wanting to go live in a cave somewhere, a hermit not forced to have social intercourse with anyone. Therefore I was astonished to hear him own up to having a hero.

The only racers other than the deceased Ghoulson I had heard him say anything remotely complimentary about had been Dick Mann, whom Gunter praised profusely and repeatedly; a protege of Mann’s named Jimmy Plain, later badly hurt at Selma; and for whatever bizarre reason the old barnstormer and trick rider Putt Mossman. Just how foolish it feels to form a facile impression of another human being and then discover it was quite faulty came to me late last year when I had the opportunity of examining the contents of a cardboard box of belongings that amounted to Gunter’s last effects. The box was overflowing with remembrances of other racers! There were photographs of the BSA Wrecking Crew'; of a Harley-Davidson youth named Ronnie Emick who is completely forgotten now, but w ho in 1960 was considered a prodigy, and whose demise at 18 during a race won by Gunter plunged all of Ascot into mourning; some picaresque and highly personal letters from the old Harley-Davidson champion Joe Leonard; an idolatrous newspaper story about Gunter whose author, bewilderingly, was Rockwood; and the most unexpected photo of all. shot at Sacramento in either 1960 or 1961, of Harley-Davidson’s nonpareil Carroll Resweber.

I still cannot think of anyone I would have thought less likely to win Gunter’s approbation than Resweber. Not only was he of the Harley-Davidson faith, but at Ascot Resweber amounted to that rarest of things; a valid and unyielding threat to the Gold Stars. Along with Bart Markel, he w'as the only one. What I have neglected to mention until now was that Ascot w'as the only half-mile in America that was poison to Harley-Davidson. Not only was it impossible for one of them to defeat a Gold Star at Ascot, but unless track conditions were abnormal, it was not possible for a KR to look anything but ridiculous in the vain attempt. Oh. a Harley-Davidson might win the novice main event, and some terrifyingly reckless amateur aboard a Harley-Davidson —Marshall (Earthquake) Lamm, say—might tank-slap to a victory in the amateur main (although the Gold Star influence was felt regularly in that rugged division, too), but in the expert feature, against the lithe, quick BSA Singles. any KR was certain to root and> wallow and look like nothing so much as one of those gluttonous mammals HarleyDavidsons have long been nicknamed. Seldom could Troy Lee, Johnny Gibson or even the dedicated brawler Don Hawley win; and the only out-of-state racer on a Harley-Davidson ever to accomplish a victory had been Bart Markel, who was in searing form during the inaugural weeks of 1960.

Then Resweber. the greatest Number 1, journeyed west in July, bringing w'ith him a KR like none we had ever seen. It appeared to be lower, smaller, and even more nimble than the Gold Star. Resw'eber had craft and finesse. Cannily scrutinizing the Gold Stars, he stuck his delicate, undersized Harley into a widening lead with less than four miles of the Eight Mile National to go. Abruptly Gunter’s No. 3 appeared from nowhere and went past Resweber as if he were a nobody. Seeing the gap between Gunter and himself widening, and the distance between himself and Stuart Morley, who was riding Dick Bultman’s BSA, a sister Gold Star to Gunter’s, closing, Resweber uncharacteristically did it all wrong in the tightening north turn. Down he went in an uninjured but mortified heap.

Gunter appeared to force Markel into an almost identical error two years later, while scoring the second, and best, of his three Eight Mile National wins. By most accounts Gunter won this race off the track. The commotion began when his black Ford Ranchero with his immaculate Gold Star (if it wasn’t immaculate, Albert wouldn’t come) in its bed was seen arriving so tardily that Ascot’s back pit gate was shutting and he almost missed registration. Once inside the grounds Gunter wouldn’t permit Markel or anyone a close look at the Gold Star—I seem to recall he’d brought w ith him a hard-faced Polynesian, supposedly a black belt karate man, to see to that. Gunter’s lateness, gossip spreading across the pits had it. had come about because all afternoon he’d been preening his Gold Star. He had it hot.

Still Gunter refused to talk to Markel. or to acknowledge his presence in any way. Markel was outwardly unmoved by the snub, and established a speed record winning his qualifying heat. A Harley-Davidson making an Ascot record! Gunter, in the same heat, almost had to run over the top of Markel’s teammate, traveling companion. and blocker, Tony Murguia.

The apology I heard Gunter delivering to the irate Murguia afterward, and which I noticed Markel listening to as well, seemed genuine. It also was couched in innuendo. Everything Gunter did that exciting night, including arriving late, seemed to be calculated to put Markel off balance. There was a curious theory, advanced I think by Neil Keen, that Markel could be psyched out. I know that all of those old acquaintances of Gunter’s who once held him in high esteem, but today are mistrustful of his reputation and view him as a racer who has been over-propagandized, and who are convinced that his^ last-second arrival at this particular National wasn’t intentional, but purely be-, cause Gunter had procrastinated about getting his Gold Star ready, will find that* fanciful. They also are aware of w hat happened later. Markel made a mysterious, stuttering start and Gunter, ordinarily mediocre from the standing start, got a tre* mendously proficient one. Gunter led^ every lap of the Eight Mile National, while Markel finally crashed and fell off chasings him.

“Gunter was never, ever, friendly to me,” Markel told me with bemusement years later. Their lives touched on twxS future occasions, both of them memorable.

At Sacramento later in 1962 I observed” Markel’s Llarley-Davidson encroaching on the portion of the narrow corner groove already occupied by Gunter’s Gold Star. 1^; was the last lap of a National that Gunter, until getting crowded, seemed to be win-» ning. Markel won.

At Tulare in 1966. Markel was on the verge of collecting his third seasonal championship for Harley-Davidson. Gunter, by rude comparison, was not quite two years recovered from his accident at Dodge City, when he swerved off the track and his head, made contact with a slab of concrete. His irascibility had worsened, and his interestin racing subsequently slackened. He had degenerated into a rather pitiable hasbeen racing not a BSA, but a Matchless, one that was immaculate in the Albert Gunter tradition. Markel, in the Tulare pits, noticed it and dared a closer look at it.

“Go on. get the hell out of here.” yelled Gunter angrily. When his order went smilingly unheeded by Markel, he summarily directed his black belt body guard, still with Gunter after all the years, to give Markel a good beating. The right of Gunter’s karatist to continue wearing his black belt was up for serious debate afterward. Markel, the old Golden Gloves finalist, promptly knocked him down once or, depending upon who is spinning the tale, twice.

The axiom that big egos make big money is subscribed to by many in racing, but it certainly never applied to Gunter, whose ego may have been the largest one of them all. Not that he ever lacked opportunities. Worthwhile offers of employment came Gunter's way when he was at the top of his powers and long after he wasn’t. Whatever jobs his racing reputation earned him, his misanthropy lost him. Dan Gurney, through the seasons one of the most hardened of Ascot devotees (Gurney, in 1959. was the kind individual who informed me of the only place I should spend my Friday nights), gave Gunter a post on his fledgling All American Racers championship race car team. Gunter had long wanted the opportunity to design, and perhaps pilot, race cars, and this was a particularly outstanding one. Of course he spoiled it. But like so many of the other things Albert Gunter ever spoiled (going out of his way. in his last, bitter years, to insult and alienate just about anyone and everyone who had been remotely close to him) he did so in such a gross, overstated manner, that it was far more comic than sad. After skeptically examining a set of blueprints drawn up by the top performance engineer at Ford Motor Co., Gunter contemptuously tossed the blueprints away and thunderously called the engineer a fool, that anyone so incompetent as he didn’t deserve to be employed anywhere. The explosion finished Gunter at Ford, and was one of the many things to finish him with Gurney and cost him his position^ at All American Racers.

Repudiating racing. Gunter in early 1976, as he was coming out of the hospital, gave me an earthy description of how valueless everything he had done WTÍS. He railed bitterly against his ego. which he blamed for leading him into racing. His^ bitterness became savage when he spoke of how little financial gain he or any of his era's principals, including Dick Mann and Harley-Davidson compeers Resweber and Markel, ever derived. 1 told him no one who ever saw him make a Gold Star go could forget it. and he fulminated that it*, didn’t deserve remembrance.

Roxy Rockw;ood remembered. Two months after Gunter's passing I was at San Jose for the National and just as the program opened the familiar voice asked the crowd for a minute of standing silence in tribute to the late Albert Gunter.

An involuntary smile which implied no disrespect for the memory of Gunter., flashed onto my face. Suddenly in my mind I wTis picturing another occasion, now more than a decade and a half in the past, and another well-intended request for quiet from Rock wood, and what Gunter's unimaginably abusive reaction to if had been. How' easy it was to envision what Albert’s behavior, were he only with us at that moment, might have been. How' loudly he would have cursed. How furious he would have become!