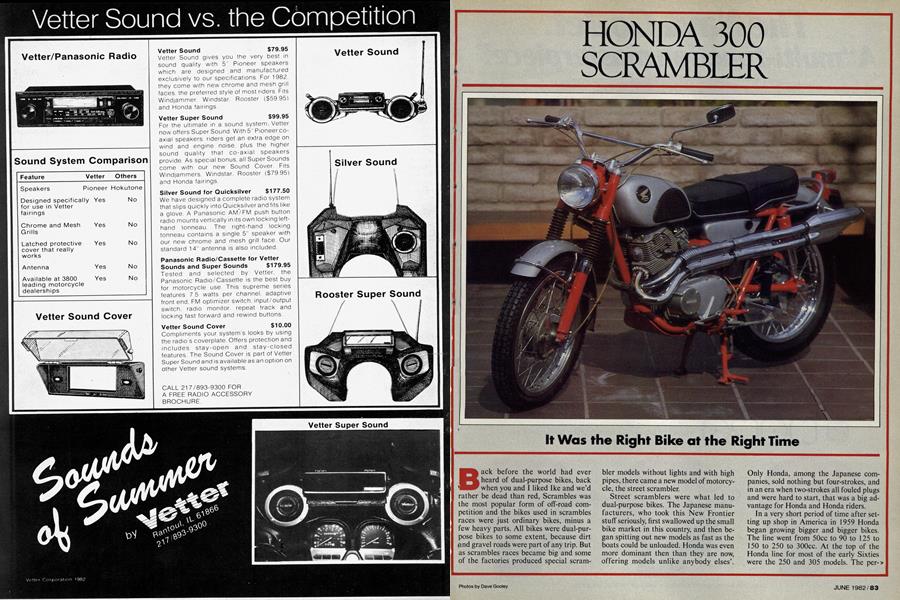

HONDA 300 SCRAMBLER

It Was the Right Bike at the Right Time

Back before the world had ever heard of dual-purpose bikes, back when you and I liked Ike and we’d rather be dead than red, Scrambles was the most popular form of off-road competition and the bikes used in scrambles races were just ordinary bikes, minus a few heavy parts. All bikes were dual-purpose bikes to some extent, because dirt and gravel roads were part of any trip. But as scrambles races became big and some of the factories produced special scrambler models without lights and with high pipes, there came a new model of motorcycle, the street scrambler.

Street scramblers were what led to dual-purpose bikes. The Japanese manufacturers, who took this New Frontier stuff seriously, first swallowed up the small bike market in this country, and then began spitting out new models as fast as the boats could be unloaded. Honda was even more dominant then than they are now, offering models unlike anybody elses’.

Only Honda, among the Japanese companies, sold nothing but four-strokes, and in an era when two-strokes all fouled plugs and were hard to start, that was a big advantage for Honda and Honda riders.

In a very short period of time after setting up shop in America in 1959 Honda began growing bigger and bigger bikes. The line went from 50cc to 90 to 125 to 150 to 250 to 300cc. At the top of the Honda line for most of the early Sixties were the 250 and 305 models. The performance versions of these, the CB models, were the bikes that established Honda’s high performance image, with acceleration and speed that matched lots of bigger displacement machines.

Honda’s model designations at the time were not simple. Letters designated the types of bikes, and numbers that didn’t correspond to engine size were attached to identify particular models. For instance,

the standard model 250 touring bike was the C72, the C being the letter for all Honda street machines, and the 72 used for the 250. When a sporting model of the street bike was introduced, it became the CB72, and when a street scrambler was introduced in 1961 it was the CL72. All these letter designations were added to the

creating model 77, the as C77, the CB77 300 or and 305 CL77. was called,

These big Hondas were like no other motorcycle seen in the early Sixties. They had two cylinder four-stroke engines, with a single overhead camshaft mounted atop the slightly inclined engine. The horizontally-split aluminum crankcase housed a 180° roller bearing crankshaft for the export models, and a 360° crank for domestic models. The 180° cranks on the U.S. models were supposed to be smoother running at high engine speeds. Bore and stroke of the 250 were 54mm; the 305 got a larger 60mm bore and kept the 54mm stroke. Two big Keihin carbs kept the high-revving engine fed with fuel and air.

While these engines were not like the other Japanese engines of their day, they did bear some resemblance to NSU motorcycle engines made a decade before. They also started a trend that Honda engines today continue: they had a high redline. When fast big bore machines would spin to maybe 6000 or 7000 rpm, and twostroke Twins would peak at 8000 rpm, the Hondas developed maximum power at 9200 rpm and would rev to 10,000 rpm. These were also peaky engines, not developing much power below 6000 rpm, but running cleanly at all speeds.

Some other Honda traits were changing at this time, and the Scrambler models were the first to change. Until the scramblers, Hondas didn’t use full cradle tube frames. Hondas always had stressed engines and no downtubes, a practice used on racing and street Flondas. The smaller Hondas and Dream touring models carried this one step farther and used weldedup stamped steel backbones for the frames, usually combined with pressedsteel fork legs and pivot links at the bottom of these. It wasn’t just Honda that did this, but Yamaha and Suzuki, too, and some of these models gave non-cradle frames a bad name they haven’t entirely escaped.

The CL Hondas, first the 250, then the 305, came with full cradle tube frames. A big single downtube forked into a pair of lower tubes, holding a skid plate. The rear portion of the frame had tubes running outside the chain, back to the top shock mount, where it, too, was highly visible. Frames were painted either black or red, and the red frame models in particular were very much different looking from the Dream or Super Hawk models.

Besides the difference in frames, there were the high pipes on the scramblers, wrapping around the left side of the bike, with a long row of grid-like heat shields on the side and an easily removable muffler fastened to the end of the staggered pipes. In no more time than it took to adjust the chain, a 305 Scrambler owner could pull the muffler on his bike, and if the local officials frowned on this, most Honda dealers stocked Snuff-R-Nots, small washers that could be installed in the back of the exhaust pipes to take some of the bite from the raspy blat of the scrambler’s exhaust. Then with a twist of a knob on the side of the Snuff-R-Nots the washers could be twisted open for all the noise the rider wanted.

These two features; the honest-to-God frame and the loud high pipes, were the Scrambler’s secret of success. Compared with the Super Hawk, the Scrambler was slightly slower at the dragstrip because of its less efficient exhaust. It didn’t have push-button starting or a tach, and it didn’t have a nice, big chrome-plated gas tank. Instead, it had a smaller silver painted tank with rubber knee pads on the sides and a little round Honda badge on the front of the tank.

Hondas in the Sixties were always fast bikes, but not the fastest. They hit an ideal of performance, offering enough power and speed so they could keep up with much larger bikes, but without creating any fuss. Honda 305 Scrambler riders didn’t have to carry spare plugs with them, and a couple of easy stomps on the kickstart always fired the engine, although it took a few minutes before the big carbs would work without the choke. These civilized machines could turn quarter miles in the 16-sec. bracket, while getting 50 to 60 mpg and without leaking any oil. Or having oil added to the gas tank. Whatever a motorcyclist was used to, the Honda 305s felt good. Big bike riders could appreciate the light, nimble handling and the lively engine. Riders of smaller bikes and twostrokes could thrill to the sound of the exhaust and the big-bike ride and power. The 305, especially the Scrambler, was a fullsize motorcycle, capable of being ridden anywhere, any time.

Despite the high pipes, Honda’s Scramblers and everyone else's weren’t happiest off road. There wasn’t much suspension travel, the machines were heavy, they didn’t steer particularly well, and the power was too cammy for good dirt use. They did, however, let motorcyclists buy good looking bikes and this told the manufacturers that there was a market for good off-road useable equipment.

Dual purpose bikes like Yamaha’s DT-1, Suzuki’s TS250 and Honda’s XL250 replaced the street scramblers for off-road work. Bigger street bikes were less adaptable to street scramblers, too, though the 450 and 350 Hondas were offered as street scramblers. When Honda switched to Fours, the street scramblers went away.

Thousands of Scramblers in 250 and 305 configuration were produced, but few are around as collector’s items. The bikes were too useable and too inexpensive at $720, and they quickly were turned into rat bikes, with rusty spokes and torn seats. There’s still at least one original Scrambler out there. It’s part of the Hillcrest Motors Collection in Beverly Hills, California. The owner of the collection bought the CL77 new in 1965 and has kept it just like it came, with only 6.5 mi. on the odometer. This particular bike is a 1965 model, the first year the big engine Scrambler was made. That year it was called the Scrambler 300, not the 305, and only 5700 of them made it into the country before the 305 Scrambler was introduced the next year. Then for a couple of years Honda sold nearly 30,000 of the 305 Scramblers per year until the model faded away, replaced by bigger street bikes and lighter dirt bikes.

There’s no question today’s big single cylinder dual purpose bikes and small street Twins are better machines than the 305 Scrambler. They are faster and smoother and more comfortable and more economical. But something is missing, too. Today’s Twins don’t have the excitement of loud high pipes, and the dual purpose bikes can’t humble big bikes like the old 305 could. Maybe all the bikes have gotten too equal, a problem the motorcyclist in 1965 didn’t have. Buying a 305 Scrambler really was a way to outsmart the system,