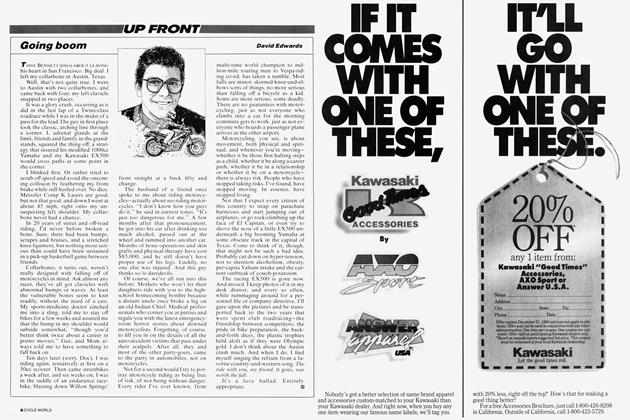

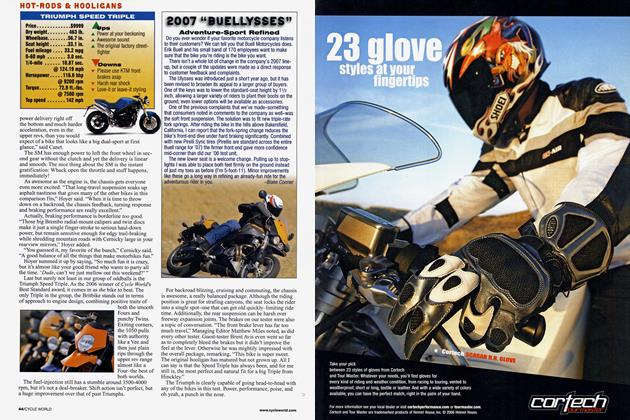

ROBERTS REPLICA

THE EDITOR BUILDS A GENUINE STREET-TRACKER

I CAN'T PINPOINT THE EXACT MOMENT I fell in love with flat-track racing.

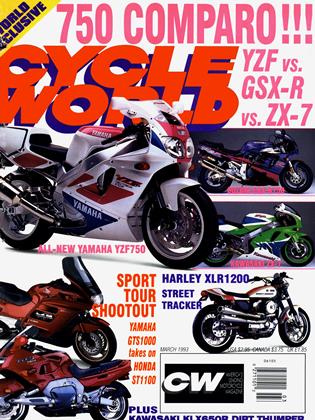

Perhaps it was the amateur contests my dad took me to when I was a kid. Perhaps it was devouring the exploits of Nixon, Mann, Romero, et al on the pages of a monthly magazine. Perhaps it was watching Kenny Roberts corner so hard at the Astrodome TT that his Yamaha’s engine cases dug furrows in the dirt. Perhaps it was cheering at San Jose as Jay Springsteen and Ricky Graham on a pair of Harley XRs traded the lead 30 times in a 25lap race. Perhaps it was watching Bubba Shobert on the RS750 Honda come boiling out of Turn Four at the Sacramento Mile in the most perfect feet-up power slide, calmly glancing over his shoulder to check out the competition.

Or perhaps it’s the machinery itself. There’s no more honest a motorcycle than a flat-track bike: all engine and wheels tied together by a minimum of metal, so dedicated to light weight there’s not even a front fender. And the sound. Whether it’s the syncopated bazooka-booms of an XR-750 or the air-ripping barks of the now-obsolete Triumph, BSA and Yamaha parallelTwins, flat-trackers have always been ecstasy for the ears.

So, how could I help but buy an outto-pasture Champion-framed Yamaha 750, then turn it into a minimalist streetbike? After all, this was the same kind of machine that in 1973 Kenny Roberts rode to his first Grand National Championship. Racebike history can be hard to trace, but this particular model seems to be one of the first Champion-Yamaha collaborations, and may have been ridden by Canadian racer Yvon DuHamel, among others, before being relegated to the back of a garage.

To transform the Yamaha from racebike to road-ready, I enlisted the ser-

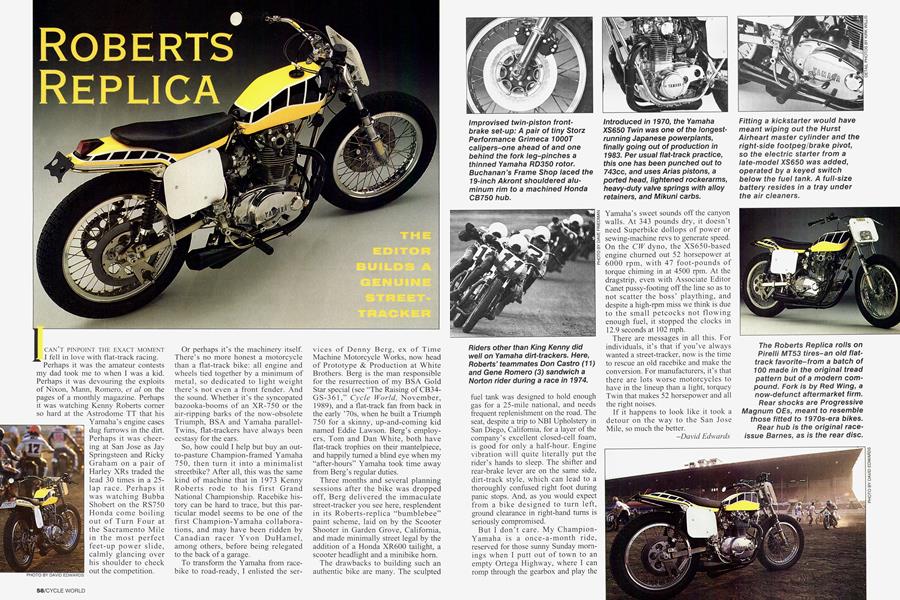

vices of Denny Berg, ex of Time Machine Motorcycle Works, now head of Prototype & Production at White Brothers. Berg is the man responsible for the resurrection of my BSA Gold Star special (see “The Raising of CB34GS-361,” Cycle World, November, 1989), and a flat-track fan from back in the early ’70s, when he built a Triumph 750 for a skinny, up-and-coming kid named Eddie Lawson. Berg’s employers, Tom and Dan White, both have flat-track trophies on their mantelpiece, and happily turned a blind eye when my “after-hours” Yamaha took time away from Berg’s regular duties. The drawbacks to building such an authentic bike are many. The sculpted fuel tank was designed to hold enough gas for a 25-mile national, and needs frequent replenishment on the road. The seat, despite a trip to NBI Upholstery in San Diego, California, for a layer of the company’s excellent closed-cell foam, is good for only a half-hour. Engine vibration will quite literally put the rider’s hands to sleep. The shifter and rear-brake lever are on the same side, dirt-track style, which can lead to a thoroughly confused right foot during panic stops. And, as you would expect from a bike designed to turn left, ground clearance in right-hand turns is seriously compromised.

Three months and several planning sessions after the bike was dropped off, Berg delivered the immaculate street-tracker you see here, resplendent in its Roberts-replica “bumblebee” paint scheme, laid on by the Scooter Shooter in Garden Grove, California, and made minimally street legal by the addition of a Honda XR600 tailight, a scooter headlight and a minibike horn.

But I don’t care. My ChampionYamaha is a once-a-month ride, reserved for those sunny Sunday mornings when I putt out of town to an empty Ortega Highway, where I can romp through the gearbox and play the

Yamaha’s sweet sounds off the canyon walls. At 343 pounds dry, it doesn’t need Superbike dollops of power or sewing-machine revs to generate speed, On the CW dyno, the XS650-based engine churned out 52 horsepower at 6000 rpm, with 47 foot-pounds of torque chiming in at 4500 rpm. At the dragstrip, even with Associate Editor Canet pussy-footing off the line so as to not scatter the boss’ plaything, and despite a high-rpm miss we think is due to the small petcocks not flowing enough fuel, it stopped the clocks in 12.9 seconds at 102 mph.

There are messages in all this. For individuals, it’s that if you’ve always wanted a street-tracker, now is the time to rescue an old racebike and make the conversion. For manufacturers, it’s that there are lots worse motorcycles to have in the lineup than a light, torquey Twin that makes 52 horsepower and all the right noises.

If it happens to look like it took a detour on the way to the San Jose Mile, so much the better.

-David Edwards