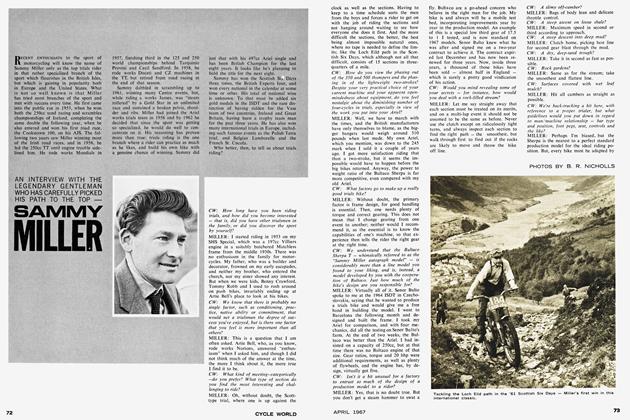

TWENTY YEARS OF TRIALS

MAX KING

WHEN MOTORCYCLE SPORT began to get underway after World War II, British motorcycle manufacturers were too preoccupied in producing normal road bikes to give more than sparse attention to the needs of sportsmen. It was not long, though, before the bigger firms took much more than a passing interest in trials and scrambles. In 1946, Ariel, BSA, AJS, Matchless, Royal Enfield and Triumph began to sponsor works teams and competition shops set eagerly about the job of “tailoring” virtually standard machines to suit them for trials.

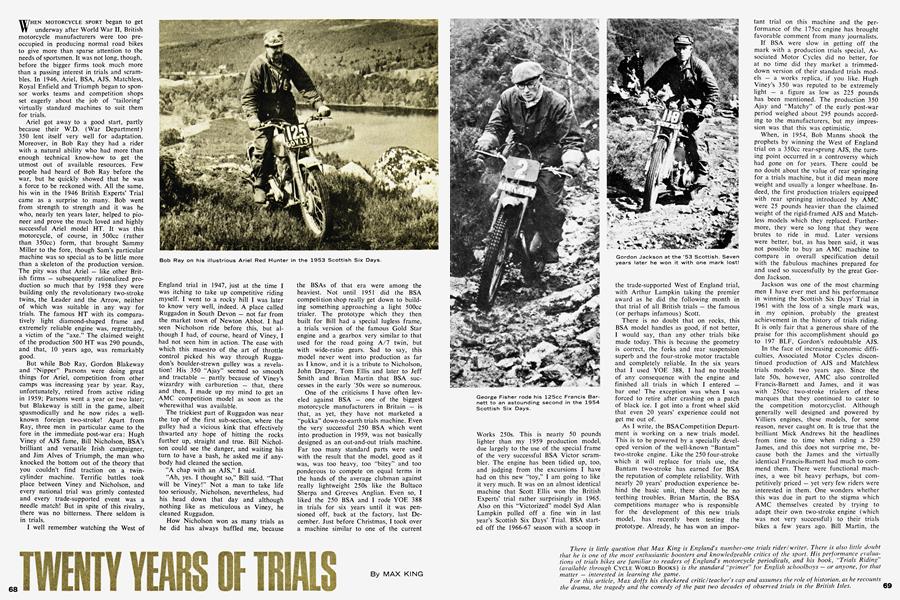

Ariel got away to a good start, partly because their W.D. (War Department) 350 lent itself very well for adaptation. Moreover, in Bob Ray they had a rider with a natural ability who had more than enough technical know-how to get the utmost out of available resources. Few people had heard of Bob Ray before the war, but he quickly showed that he was a force to be reckoned with. All the same, his win in the 1946 British Experts’ Trial came as a surprise to many. Bob went from strength to strength and it was he who, nearly ten years later, helped to pioneer and prove the much loved and highly successful Ariel model HT. It was this motorcycle, of course, in 500cc (rather than 350cc) form, that brought Sammy Miller to the fore, though Sam’s particular machine was so special as to be little more than a skeleton of the production version. The pity was that Ariel — like other British firms — subsequently rationalized production so much that by 1958 they were building only the revolutionary two-stroke twins, the Leader and the Arrow, neither of which was suitable in any way for trials. The famous HT with its comparatively light diamond-shaped frame and extremely reliable engine was, regrettably, a victim of the “axe.” The claimed weight of the production 500 HT was 290 pounds, and that, 10 years ago, was remarkably good.

But while Bob Ray, Gordon Blakeway and “Nipper” Parsons were doing great things for Ariel, competition from other camps was increasing year by year. Ray, unfortunately, retired from active riding in 1959; Parsons went a year or two later; but Blakeway is still in the game, albeit spasmodically and he now rides a wellknown foreign two-stroke! Apart from Ray, three men in particular came to the fore in the immediate post-war era: Hugh Viney of AJS fame, Bill Nicholson, BSA’s brilliant and versatile Irish campaigner, and Jim Alves of Triumph, the man who knocked the bottom out of the theory that you couldn’t find traction on a twincylinder machine. Terrific battles took place between Viney and Nicholson, and every national trial was grimly contested and every trade-supported event was a needle match! But in spite of this rivalry, there was no bitterness. There seldom is in trials.

I well remember watching the West of England trial in 1947, just at the time I was itching to take up competitive riding myself. I went to a rocky hill I was later to know very well, indeed. A place called Ruggadon in South Devon — not far from the market town of Newton Abbot. I had seen Nicholson ride before this, but although I had, of course, heard of Viney, I had not seen him in action. The ease with which this maestro of the art of throttle control picked his way through Ruggadon’s boulder-strewn gulley was a revelation! His 350 “Ajay” seemed so smooth and tractable — partly because of Viney’s wizardry with carburetion — that, there and then, I made up my mind to get an AMC competition model as soon as the wherewithal was available.

The trickiest part of Ruggadon was near the top of the first sub-section, where the gulley had a vicious kink that effectively thwarted any hope of hitting the rocks further up, straight and true. Bill Nicholson could see the danger, and waiting his turn to have a bash, he asked me if anybody had cleaned the section.

“A chap with an AJS,” I said.

“Ah, yes. I thought so,” Bill said. “That will be Viney!” Not a man to take life too seriously, Nicholson, nevertheless, had his head down that day and although nothing like as meticulous as Viney, he cleaned Ruggadon.

How Nicholson won as many trials as he did has always baffled me, because the BSAs of that era were among the heaviest. Not until 1951 did the BSA competi tion shop really get down to building something approaching a light 500cc trialer. The prototype which they then built for Bill had a special lugless frame, a trials version of the famous Gold Star engine and a gearbox very similar to that used for the road going A/7 twin, but with wide-ratio gears. Sad to say, this model never went into production as far as I know, and it is a tribute to Nicholson, John Draper, Tom Ellis and later to Jeff Smith and Brian Martin that BSA successes in the early ’50s were so numerous.

One of the criticisms I have often leveled against BSA — one of the biggest motorcycle manufacturers in Britain — is that, as yet, they have not marketed a “pukka” down-to-earth trials machine. Even the very successful 250 BSA which went into production in 1959, was not basically designed as an out-and-out trials machine. Far too many standard parts were used with the result that the model, good as it was, was too heavy, too “bitey” and too ponderous to compete on equal terms in the hands of the average clubman against really lightweight 250s like the Bultaco Sherpa and Greeves Anglian. Even so, I liked the 250 BSA and I rode YOE 388 in trials for six years until it was pensioned off, back at the factory, last December. Just before Christmas, I took over a machine similar to one of the current Works 250s. This is nearly 50 pounds lighter than my 1959 production model, due largely to the use of the special frame of the very successful BSA Victor scrambler. The engine has been tidied up, too, and judging from the excursions I have had on this new “toy,” I am going to like it very much. It was on an almost identical machine that Scott Ellis won the British Experts’ trial rather surprisingly in 1965. Also on this “Victorized” model Syd Alan Lampkin pulled off a fine win in last year’s Scottish Six Days’ Trial. BSA started off the 1966-67 season with a scoop in the trade-supported West of England trial, with Arthur Lampkin taking the premier award as he did the following month in that trial of all British trials — the famous (or perhaps infamous) Scott.

There is no doubt that on rocks, this BSA model handles as good, if not better, I would say, than any other trials bike made today. This is because the geometry is correct, the forks and rear suspension superb and the four-stroke motor tractable and completely reliable. In the six years that I used YOE 388, I had no trouble of any consequence with the engine and finished all trials in which I entered — bar one! The exception was when I was forced to retire after crashing on a patch of black ice. I got into a front wheel skid that even 20 years’ experience could not get me out of.

As I write, the BSACompetition Department is working on a new trials model. This is to be powered by a specially developed version of the well-known “Bantam” two-stroke engine. Like the 250 four-stroke which it will replace for trials use, the Bantam two-stroke has earned for BSA the reputation of complete reliability. With nearly 20 years’ production experience behind the basic unit, there should be no teething troubles. Brian Martin, the BSA competitions manager who is responsible for the development of this new trials model, has recently been testing the prototype. Already, he has won an important trial on this machine and the performance of the 175cc engine has brought favorable comment from many journalists.

If BSA were slow in getting off the mark with a production trials special, Associated Motor Cycles did no better, for at no time did they market a trimmeddown version of their standard trials models — a works replica, if you like. Hugh Viney’s 350 was reputed to be extremely light — a figure as low as 225 pounds has been mentioned. The production 350 Ajay and “Matchy” of the early post-war period weighed about 295 pounds according to the manufacturers, but my impression was that this was optimistic.

When, in 1954, Bob Manns shook the prophets by winning the West of England trial on a 350cc rear-sprung AJS, the turning point occurred in a controversy which had gone on for years. There could be no doubt about the value of rear springing for a trials machine, but it did mean more weight and usually a longer wheelbase. Indeed, the first production trialers equipped with rear springing introduced by AMC were 25 pounds heavier than the claimed weight of the rigid-framed AJS and Matchless models which they replaced. Furthermore, they were so long that they were brutes to ride in mud. Later versions were better, but, as has been said, it was not possible to buy an AMC machine to compare in overall specification detail with the fabulous machines prepared for and used so successfully by the great Gordon Jackson.

Jackson was one of the most charming men I have ever met and his performance in winning the Scottish Six Days’ Trial in 1961 with the loss of a single mark was, in my opinion, probably the greatest achievement in the history of trials riding. It is only fair that a generous share of the praise for this accomplishment should go to 197 BLF, Gordon’s redoubtable AJS.

In the face of increasing economic difficulties, Associated Motor Cycles discontinued production of AJS and Matchless trials models two years ago. Since the late 50s, however, AMC also controlled Francis-Barnett and James, and it was with 250cc two-stroke trialers of these marques that they continued to cater to the competition motorcyclist. Although generally well designed and powered by Villiers engines, these models, for some reason, never caught on. It is true that the brilliant Mick Andrews hit the headlines from time to time when riding a 250 James, and this does not surprise me, because both the James and the virtually identical Francis-Barnett had much to commend them. There were functional machines, a wee bit heavy perhaps, but competitively priced — yet very few riders were interested in them. One wonders whether this was due in part to the stigma which AMC themselves created by trying to adapt their own two-stroke engine (which was not very successful) to their trials bikes a few years ago. Bill Martin, the one-time Devonshire ace, was the only man I knew who could ride an AMCpowered trials model with consistent success, but even he found his James a bit of a handful — ’though he was too loyal to admit it!

There is little question that Max King is England’s number-one trials rider/writer. There is also little doubt that he is one of the most enthusiastic boosters and knowledgeable critics of the sport. His performance evaluations of trials bikes are familiar to readers of England’s motorcycle periodicals, and his book, “Trials Riding” (available through CYCLE WORLD BOOKS) is the standard “primer” for English schoolboys — or anyone, for that matter — interested in learning the game.

For this article, Max doffs his checkered critic/teacher’s cap and assumes the role of historian, as he recounts the drama, the tragedy and the comedy of the past two decades of observed trials in the British Isles.

It was quite a different story in the early fifties. Indeed, between 1950 and 1957, Francis-Barnett and James were easily the most popular lightweights in Britain! I had my first real taste of success in one-day trials when I bought a Model “60” Francis-Bamett Falcon in 1952. The following year I changed it for the improved Model 62, and when I had graduated from this machine I kept it in trim for my son, Rob to take over when he was old enough. Only recently did it leave my ownership and since the young rider who bought it has, himself, graduated to a BSA (strangely enough the actual machine on which my son subsequently became an “expert”), I am sorely tempted to buy back the Fanny-B for old time’s sake.

Weighing just 200 pounds and powered by a Villiers 7E high-compression engine with four speed gearbox, this model, in its day, was a delightful little bike. All it really needed was a little more power, a spring frame and more robust forks. In time improved suspension came, but up went the weight, and with no increase in power, performance and handling were affected. I was lucky I was able to get hold of a very light “one-off” ex-Works model, circa 1955. Two years later I was offered a factory “fettled” version of the last trials model to be built by Francis & Barnett, Ltd., before they were taken over by AMC. I accepted the offer, but I would have been wiser to have stuck to the earlier machine; it was much better.

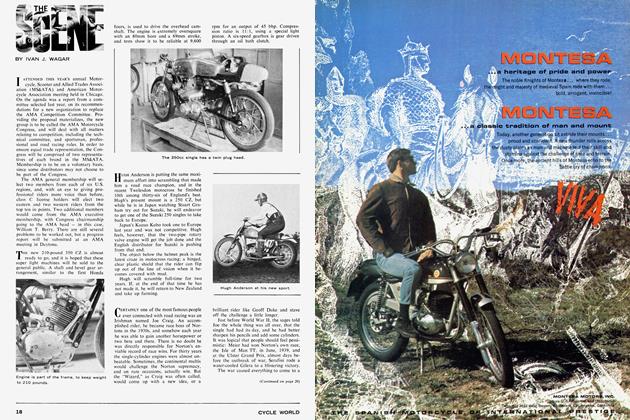

It would be wrong to leave this note about Francis-Barnett and James trailers without mentioning the men who brought fame to these marques. George Fisher, perhaps more than anyone else, was the rider who really put paid to the myth that a lightweight two-stroke was a toy rather than a trials winning “tool.” Fisher’s remarkable run of success in Nationals on 125, 197 and 201cc Francis Barnetts helped to pave the way for the domination which, from the late ’50s right up to the present day, the two-stroke has maintained in trials. Among George’s many fine achievements, the most remarkable were his two runnerup awards in the “Scottish” in 1954 (on a 125!) and 1955. I had the anguish (being an “F-B” man at the time) of seeing Fisher virtually throw the 1955 Scottish into Jeff Smith’s lap by what looked like a quite unnecessary “dab” on the tight right-hander leading to the “Devil’s Staircase.” An attack of nerves, maybe, but whatever the cause, it cost poor George Fisher the trial.

Other riders who will always be associated with Francis-Barnett are Arthur Shutt and Brian Martin who, like Fisher, did great things on 125s. Two of the pioneers were Ernie Smith the then competitions “gaffer” and burly Jack Botting. Of James fame were “Professor” Bill Lomas (who was also a top-flight road racer), Bill Martin and Bryan Povey, both of whom won the West of England trial on 201cc James Commando models.

Another manufacturer with a fine postwar record is Triumph. As I mentioned earlier, it had been the common belief that a twin-cylinder machine with its smooth torque was not suited to trials. The idea was that it would be difficult to control in mud and that grip would be hard to find. In truth, relatively few riders really mastered the technique of riding a twin, but one man who did was Somerset’s Jimmy Alves. Jim and his Triumph Trophy are almost legendary, and what a joy it was to watch the master in action. Alves could almost make that delightfully quiet engine talk! His throttle control was sheer perfection, and although Jim did not boast quite as many outright wins as Nicholson and Viney, in his day he was one of the three finest trials men in the game. In the Triumph team of the 1949 to 1958 era with Alves were Peter Hammond and the “evergreen” John Giles.

I was so impressed with the Triumph Trophy as a dual-purpose machine that in 1950 I bought one. Frankly, I could not master it in mud and did not distinguish myself in one-day sporting trials. I found it ideal, however, for long distance events like the Land’s End and the Exeter — two of the Motor Cycling Club’s annual classics. Thanks to the Trophy, I never won less than a first class award in these trials, and on three occasions I was a member of the winning Motorcycle team. Yes, the Triumph Trophy is a machine I shall remember with the utmost satisfaction. Later models — from about 1955 onwards — were equipped with springframes. They were longer and heavier, but even today the model of this name is used with distinction, particularly as an enduro machine.

(Continued on page 90)

When production of the 500cc Trophy TR5 ceased in 1957, Triumph turned to their 199cc Cub for trials. This machine, the T-20C, weighed about 200 pounds. In 1962, it was available in works replica form; it handled well and was very peppy. Alves used a Cub very successfully but not, I felt, with the same deftness of the Trophy. All the same, this model sold extremely well, partly because it was competitively priced. Riders of the Trials Cub whose names will go down in the annals are Artie Ratcliffe, Ray Sayer and young Gordon Farley the recent winner of the National Vic Brittain Trial. It is sad that a firm with such a fine record should now have ceased to produce a trials machine. Triumph’s long run of successes in the International Six Days’ Trial must in itself be an achievement of which they are justly proud.

The name Norton has not yet featured in this story, yet it was this firm who, in 1948, made the first serious attempt to market a “cut-down” trials iron. This was the renowned Norton 500T which, the makers claimed, turned the scales at only 289 pounds. True, it had a rigid frame, but weight was kept down also by the use of a light alloy head and barrel for the 490cc engine and for items like the fork bridge and speedometer head case. The gas tank was narrow and its capacity was only two gallons. In detailed layout this machine was far in advance of any comparable model of the day and it became a great favorite among the trials fraternity. What a pity that such a fine machine was taken out of production in 1954 and was never marketed with a spring frame. Two very well known members of the Norton trials team were Geoff Duke (yes, he once won a National trial) and Jeff Smith, who at that time was still in his teens.

Royal Enfield, was a firm I admired very much, both for the quality of their bikes and for their courage in pinning their faith in rear springing for trials machines long before other manufacturers were prepared to accept the idea. In the early ’50s, Johnny Brittain was one of the top six trials riders in Great Britain and his machine was a 350cc rear sprung Royal Enfield. In 1952, at the tender age of 21. Brittain put up a brilliant performance to win the British Experts’ trial by two marks over Hugh Viney. The scores, I remember, were 27 and 29 and how proud of his elder son Johnny’s father, Vic, must have been, for Vic Brittain was one of the pre-war “greats” in the trials world and the winner himself of the British Experts’ trophy in 1936 and again in 1939, when he tied with Jack Williams of Norton fame.

Enfield was the first firm to market what they described as a factory replica trials model. This machine, a 350, had a special frame and was renowned for its slow speed pulling and mechanical quietness. The biggest drawback was its weight, but among the “big bangers” it sold well until it was superseded by the trials 250 model which had the short-stroke Enfield Crusader engine. This bike, too, was popular, but it did not equal the 350 except, of course, on the score of weight.

John Brittain did well on the 250, but as business commitments grew, his appearances became less and less. Consequently, by the early '60s Johnny had faded out of the big-time trials scene. Also in the Enfield team were Pat Brittain (John’s younger brother), Peter Stirland and Peter Fletcher, who continues to have a bash in his light-hearted way on a lightened 500 special. Last year, in a barn in West Dorset, I came across an ex-Brittain 350 Royal Enfield in a fair state of preservation; it could have been bought for a song but, fool that I am, I did not bite. One day I must look in that bam again.

By the middle of the ’50s, a new name had crept into the list of British motorcycle manufacturers — Greeves. It was a name that in the next decade was to make a major impact on the competition world. Indeed, there was a time — only two or three years ago, in fact — when the bulk of the machines entered for any one-day trial were Greeves. “The ubiquitous Greeves” was a term that became very hackneyed. With its unorthodox frame construction employing a main beam of girder section cast from aluminum alloy and with leading link forks of special design, embodying bonded rubber in torsion bushes, the Greeves was one of the lightest rear sprung trialers of the day. Early models were powered by Villiers 197cc Mark 9/E engines. But in 1959, when Villiers produced their Mark 31A unit, Greeves, quick to see the growing popularity of the 250, marketed the 24TAS Scottish Trials model, which turned out to be one of the most successful machines in a long and illustrious line.

For my money, though, Greeves hit the jackpot with their model 24/TES which really was a winner. Employing a trials version of the alloy, square-barrelled 250cc engine which, reputedly, Greeves and Villiers jointly developed for scrambles, this machine combined lightness with a superb performance throughout the rev range. When, in 1964, I tested a 24/TES, I was immensely impressed with what I described as the engine’s “turbine-like power.” Indeed, the progress which Greeves had made between 1955 and 1964 was abundantly clear from the comparisons I was able to draw between my tests of one of the early 197s and the 250 24/TES. Next in line was the TFS, which boasted a suitably modified Challenger engine that again was a joint Greeves/Villiers project. Opinions on the TFS were mixed; only recently I heard this described as “the best Greeves yet,” but I could not share this view.

I would say, without hesitation, that the finest trialer made by Greeves is the current Anglian — the THS. This is a developed “edition” of the original Anglian TGS which made its debut in the Autumn of 1965 as the Essex factory’s answer to the Spanish Bultaco and it was a pretty good answer!

Greeves’ main objective in designing the Anglian was to cut down weight, and this was accomplished by quite drastic changes to the rear end and the forks in particular. The redesigned “banana” leading link forks were pounds lighter than the former type, yet they were given greater torsional stiffness and provided 35 percent more travel. By reverting to the small type front hub, two pounds were saved and steering improved. The overall result of this pruning was a 250 trials model, with most of the favored “mods” built-in, which weighed (according to the catalog) only 215 pounds.

(Continued on page 92)

I had the pleasure of testing one of the early Anglians about a year ago. Most of this test was conducted during a thaw when conditions were at their worst, but thanks to the excellent handling qualities of the Greeves, I finished a trial only four marks behind the winner, and with a bit more care I could have taken the Premier award. The fact was that, stupidly, I went the wrong side of a section “ends” card — an aberration that cost me five vital marks!

Later in the year, I tried out the current Anglian — the THS — which incorporated certain suggestions I had made and featured the new Amal “600” concentric float carburetor. This machine, in production trim, was “peppier” than the TGS, but if the internal diameter of the short exhaust tail-pipe were increased to 7/8 inch, coupled with a richer mixture setting, the performance, I have since learned, could be still further improved. I consider the Anglian THS to be the best British trials machine currently on the market and one of the two best trials models I have ever tested.

Much of the credit for the strong position Greeves now hold in the competition field is due to Bert Greeves, the firm’s chief technical director and development engineer. But another who will always be associated with Greeves is Brian Stonebridge. It was Brian who did much to put this marque on the map in the early years. The untimely death of this brilliant rider and engineer was a tragic loss to the sport of motorcycling.

So many men have done great things on Greeves trialers that it would be an injustice to mention any but those who have earned the highest honors. First and foremost among these must be Don Smith, who is now leading the 1966-67 competition for what, unofficially, is regarded as the European Trials Championship. Don is not only a great rider — I place him second only to the mighty Miller — he is one of the nicest, most level-headed men in the game. Others who have brought fame to Greeves and to themselves are Bill Wilkinson and the Davis brothers, Tony and Malcolm.

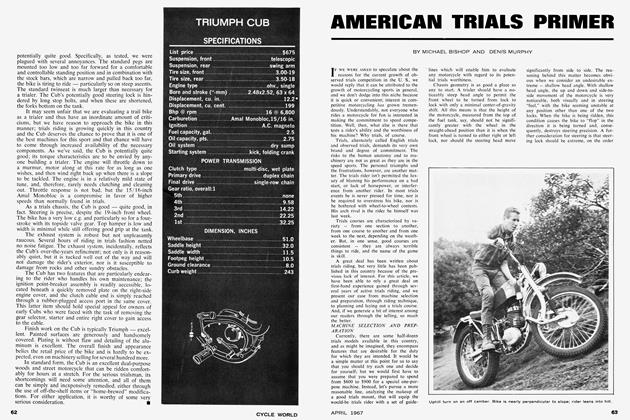

Finally, in this twenty-year review, I come to the machine which (judging from performance and handling) is in my opinion the best in the world today. I refer to the Bultaco Sherpa, the brainchild and the tool of Sammy Miller. When I tested this machine in May, 1965, I began my report by saying that this was the finest trials bike I had ever ridden. As things stand at present, this statement is still true. In terms purely of longevity, I would place the Anglian slightly ahead, because unless maintained with exceptional care, the Bultaco can be expensive to run. For some reason, the engine seems very susceptible to bearing corrosion and to oil seal failure. One tip to combat the former, which has proven effective, is to cover the air cleaner with polythene and stick a cork in the end of the exhaust pipe when washing the bike down! I understand that the latest machines are better finished and less troublesome than the earlier models, which, of course, one would expect.

Weighing only 205 pounds, the Bultaco Sherpa was the lightest 250 I had ever ridden, and the way the machine handled was a revelation. My report on the Sherpa made quite an impact and judging from one incident alone, it must, I think, have been responsible to some extent for the sudden swing to Bultaco that swept the country within a week or two of its publication. The incident I have in mind happened just before the Lyn Traders’ Trophy Trial at Whitsun, 1965. The Lyn is one of the biggest, most popular regional trials in Britain, and the secretary of the meeting telephoned me a day or two before the trial saying facetiously that he was “fed up with changing chaps entries from other machines to Bultaco.” Then he asked, “What do you want to go writing such glowing reports for?” Well, the answer, obviously, speaks for itself.

Of Sammy Miller, I have nothing but the greatest admiration. One day I look forward to writing — with Sam's cooperation — the life story of this brilliant, likeable Irishman. Miller’s brilliance does not rest with his riding; his technical knowhow is of the highest and his devotion to his profession knows no bounds. Sammy is a perfectionist in his line and nothing less than perfection will do. This is why there was that long, much publicized delay in getting the Sherpa into production. Miller had put his foot down, insisting that the “bugs” must be ironed out first. In an interview for the BBC which I had with him at this time, Sammy made no apology for the hold-up: “After all, Max,” he said, “my reputation is as much at stake as Bultaco’s . . ! ”

In this review of trials machines that have brought honor to British riders since World War II, it is perhaps ironical that I should, on the basis of present knowledge, rank a Spanish model as the tops. But this I must do, though great consolation comes from the fact that from the drawing board to the field of battle, it is Sammy Miller who has put the Bultaco Sherpa on the pedestal it occupies today.

When all is said and done, what finer recommendation could there be for any trials machine? The Sherpa is the choice of the reigning British Trials Champion, the winner of the British and Southern Experts trials of 1966 — not to mention countless International, National, Regional and Open-to-Centre trials. The Bultaco Sherpa, indeed, is the machine created and used by the man who is surely the greatest trials rider in the world today, and probably the greatest the world has even known.