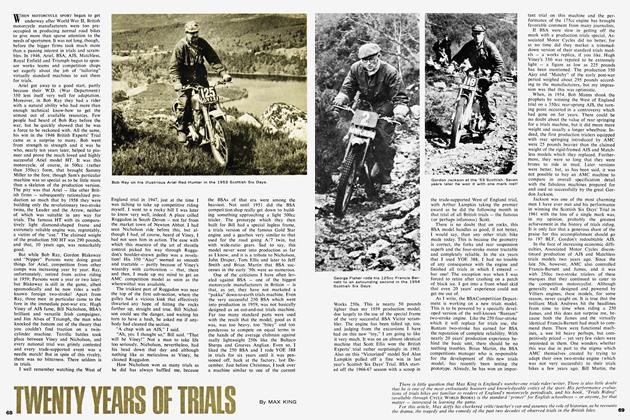

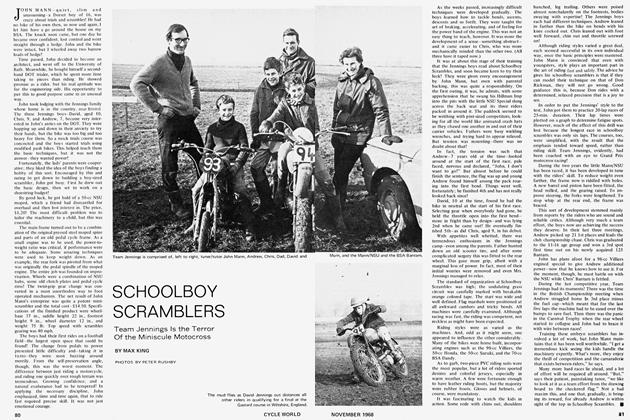

Scottish Six Days

MAX KING

LONG BEFORE my first experience of this Highland classic I had heard a lot of talk about the 'Spirit of the Scottish,' but it didn't mean much at the time. When enthusiasts talk about their favorite sports, they get carried away, so I took it all with a pinch of salt!

As things turned out, what I had been told was absolutely true. The Spirit of the Scottish is not a myth; it's real. There is a cameraderie about this trial which must be experienced to be believed. This exists among competitorsand among all involved, including organizers and the Scots themselves. The Highlanders welcome the Six Days' Trial. To them it marks the beginning of the tourist season.

Fort William during the Scottish is akin to Douglas during the Isle of Man TT races-on a much smaller scale. The whole town is taken over by chaps dressed in Barbour suits. There is a general hubbub. Odd looking motorcycles with fat rear tires and high, wide handlebars are everywhere.

Town Hall Brae, one of the observed sections, is in the center of Fort William and is approached from a market square. This section is used at least twice during the trial, and the populace turns out to enjoy the fun.

This is the Spirit of the Scottish in a tangible form, but there is much more to it than that! To understand what it is all about, the place to go is the headquarters hotel about 8:30 o'clock each evening during trials week. Here, with their mates, wives and girl friends, the riders relive their experiences of the day's run. What it amounts to is a sort of involuntary process of putting themselves right with the world-of coming to terms with their consciences! As results' time approaches, excitement grows. Then there comes a mad rush to see the huge board on which each rider's score appears, section by section, day by day. There are the looks of anguish and delight when the truth is known. There are times when some do not believe the board, because they are convinced they've been robbed.

This is the moment when riders decide whether to lodge official protests. On the whole, this step is not taken lightly. For one thing, the procedure is quite formal. The terms of protest must be stated in writing, and supported by witnesses who may be called to give evidence.

There are some, even among the top flight, who will protest only if forced to in the interest of the firms whose machinery they ride.

While the conviviality is going on among the riders in the bar, the organizers are hard at it. Throughout the day, traveling marshals have been ferrying back results books from the observers on the sections. By the end of the day's run the scores on the earlier hills will have been plotted. Even if things go smoothly, nothing can be finalized until the last books are in. Even so, more than once this year, the organization was so efficient that results were ready to publish by 7 p.m. But, on Tuesday, things were chaotic, and official results were not generally available until breakfast on Wednesday. The reason for this is a story in itself. This will come later!

For as long as is necessary, the Stewards are on hand to settle points of procedure. They meet formally to consider protests, hear witnesses and reach a verdict. Tom Melville is under constant pressure. To him come all the administrative problems-the queries and complaints from one quarter or another. But Melville's temperament is such that he remains calm throughout all this buffeting.

Plotting the route is a mammoth task. This is done long before the trial begins, and the man who has shouldered the responsibility for the job, for some years, is John Graham. It is doubtful if any clerk of the course for any sporting event in the world could be faced with a more complex job.

The total length of this year's event was about 730 miles, and there were approximately 162 observed sections in groups numbering between 1 and 15. For example, at Gordon Hill, on Thursday's run to the barren and romantic Moidart Peninsular, there was just one section. At the renowned Devil's Staircase there were three, at Bay Hill two, and so on. The next day, along the mountainous Loch Eilde Path, there were no less than 15 sections, with only short breaks between. The daily mileage varied between 67 and 159, a lot of it over rough country, including drovers' tracks on which virtually the only form of vehicular transport could be a trials motorcycle.

Route marking, Dave Fisher told me, began quite often at 4 a.m., and the job was not finished until each day's markers were removed. The signs used are the normal type made of stout cardboard. They are marked "Straight On" (black letters on white base), or by a large R (red on white), or an L (blue on white), meaning for riders to turn right or to turn left. The sections themselves are numbered consecutively on yellow painted cardboard. At strategic points, yellow stars, one on each side of the track, define the course. If a rider does not pass between the stars, or if he knocks one down, he is liable to a penalty of five marks.

Observers and marshals all work under the clerk of the course. There is one observer to each section and it is his job to record, in the appropriate column of his book, the rider's number and his performance on that section. This is done by placing an X under the heading Clean, Dab, Foot, or Stop.

Each evening there is a briefing of observers and marshals by the clerk. Marshals are stationed at important junctions to make sure both that riders take the correct routes, and to avoid holding up normal traffic. This year at the foot of Glen Ogle, riders who had tackled the hill and made the steep descent back to the highway, were confined to a passage, defined by markers, about one yard from the hedge for a distance of about 200 yards to keep the road clear of mud! When the backmarker had gone through, the mud within the markers was swept away. This is a classic example of the trouble the clerk of the course takes to maintain public relations. Unfortunately, even alter the very careful planning that goes into the route and the precision with which the route marking is done, things sometimes go wrong. This year, there was much criticism about Tuesday's route. It was more a case of the unpredictable coupled with inexperience on the part of first-timers in the trial.

There had been a delay of up to 90 mm. at a very difficult section called Leitir Bo Fionn, high above Kmlochleven. From there, riders made for Blackwater and then across moorland to Greaguianeach, Guanach Gorge and down to Spean Bridge. Trying to make up lost time, several riders, mainly newcomers, bogged down in the moor beyond Blackwater. In some cases, machines sank to the level of the fuel tanks. Many riders became com pletely exhausted and 21 were stranded until well into the night. Some struggled on, covering only a few hundred yards at a time, ultimately to take shelter in a shepherd's hut to await rescue. The competitors recovered after food, warmth and a good long sleep. To the old hands, there was no real problem. Sammy Miller and Don Smith had about 30 mm. in hand, but fastest time of the day across the moor was set by Mick Andrews and his Ossa!

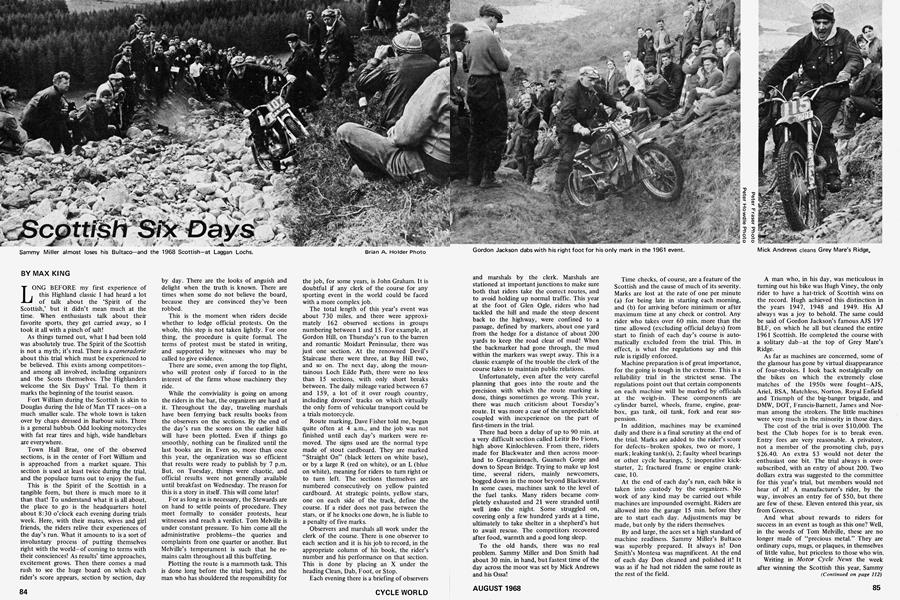

Time checks, of course, are a feature of the Scottish and the cause of much of its severity. Marks are lost at the rate of one per minute (a) for being late in starting each morning, and (b) for arriving before minimum or after maximum time at any check or control. Any rider who takes over 60 mm. more than the time allowed (excluding official delays) from start to finish of each day's course is auto matically excluded from the trial. This, in effect, is what the regulations say and this rule is rigidly enforced. Machine preparation is of great importance, for the going is tough in the extreme. This is a reliability trial in the strictest sense. The regulations point out that certain components on each machine will be marked by officials at the weigh-in. These components are cylinder barrel, wheels, frame, engine, gear box, gas tank, oil tank, fork and rear sus pension. In addition, machines may be examined daily and there is a final scrutiny at the end of the trial. Marks are added to the rider's score for defects-broken spokes, two or more, 1 mark; leaking tank(s), 2; faulty wheel bearings or other cycle bearings, 5; inoperative kickstarter, 2; fractured frame or engine crank case, 10. At the end of each day's run, each bike is taken into custody by the organizers. No work of any kind may be carried out while machines are impounded overnight. Riders are allowed into the garage 15 mm. before they are to start each day. Adjustments may be made, but only by the riders themselves. By and large, the aces set a high standard of machine readiness. Sammy Miller's Bultaco was superbly prepared. It always is! Don Smith's Montesa was magnificent. At the end of each day Don cleaned and polished it! It was as if he had not ridden the same route as the rest of the field.

A man who, in his day, was meticulous in turning out his bike was Hugh Viney, the only rider to have a hat-trick of Scottish wins on the record. Hugh achieved this distinction in the years 1947, 1948 and 1949. His AJ always was a joy to behold. The same could be said of Gordon Jackson's famous AJS 197 BLF, on which he all but cleaned the entire 1961 Scottish. He completed the course with a solitary dab-at the top of Grey Mare's Ridge.

As far as machines are concerned, some of the glamour has gone by virtual disappearance of four-strokes. I look back nostalgically on the bikes on which the extremely close matches of the 1950s were fought-AJS, Ariel, BSA, Matchless, Norton, Royal Enfield and Triumph of the big-banger brigade, and DMW, DOT, Francis-Barnett, James and Nor man among the strokers. The little machines were very much in the minority in those days. The cost of the trial is over $10,000. The best the Club hopes for is to break even. Entry fees are very reasonable. A privateer, not a member of the promoting club, pays $26.40. An extra $3 would not deter the enthusiast one bit. The trial always is over subscribed, with an entry of about 200. Two dollars extra was suggested to the committee for this year's trial, but members would not hear of it! A manufacturer's rider, by the way, involves an entry fee of $50, but there are few of these. Eleven entered this year, six from Greeves.

And what about rewards to riders for success in an event as tough as this one? Well, in the words of Tom Melville, these are no longer made of "precious metal." They are ordinary cups, mugs, or plaques, in themselves of little value, but priceless to those who win. Writing in Motor Cycle News the week after winning the Scottish this year, Sammy Miller made a strongly worded bid for cash prizes. This is what he said: "I hope 1969 will be the end of the amateur era. if the famous Alean golf tournament can put up $72,000 prize money, surely someone can chip in $6000 or $7000 for the International Scottish Six Days. If anybody put up good cash prizes for a 500-cc class or any other capacity, I would have a go."

(Continued on page 112)

Few riders are in Sammy's class. Maybe some such as Gordon Farley and Mick Andrews, with good Scottish records, would see it in the same light. It would be interesting to know. Somehow, I would be reluctant to support such a fundamental change of policy. Perhaps new ideas for this great trial would help increase its prestige, but I doubt if the organizers, with their characteristic reserve, will take kindly to Sam's suggestion.

As far as machinery goes, this must be suitable for the job. Once I saw a team of Metropolitan policemen try to get 500 Speed Twins to the top of Grey Mare's Ridge and it wasn't funny! It does not matter too much about engine size. The 125 Puchs and Suzukis, for instance, were quite impressive this year, and a 60-cc Heldun finished the course. These little machines coped well and were, on the whole, amazingly reliable. Peter Gaunt and Ray Sayer on works 128-cc Suzukis were 14th and 22nd, while Mick Bowers on a 175 BS A Bantam was 10th. Dave Rowland on a similar machine was runner-up in 1967.

My advice to anyone who is thinking of doing the Scottish is to watch it first to see what is involved, to sense the drama of the sort of battle that was waged during the early part of this year's trial, between Sammy Miller and Gordon Farley, to watch the tactics of the wily Miller, to admire the tenacity of the man.

This "Sporting Holiday in the Highlands," to quote the caption on the book of rules, is not reserved for men only. Women can and often do compete. Indeed, there is a prize for the best performance by a lady competitor. Olga Kevelos has ridden in the Scottish off and on for 20 years. In the foreward of this year's official program, she wrote: "It was in 1948 that I essayed to ride in my first Scottish. It was only my second trial and I had mercifully very little idea of what lay in front of me. Norman Hooton and the James team were my mentors and when I arrived at Fort William, where the trial then started, my head was spinning with the hair-raising stories they had told me by way of encouragement. Of the boulders as big as elephants, the death defying 1000-foot descents, the bottomless bogs and the trackless wastes marked with the whitened bones of old competitors and the dreadful orgies that took place at night.

"Of course, I took no notice, but as it happened, it all turned out to be perfectly true! And I enjoyed it all so much that I've been going back for more practically every year since."

The Spirit of the Scottish? Well, now you know what it is all about! ■