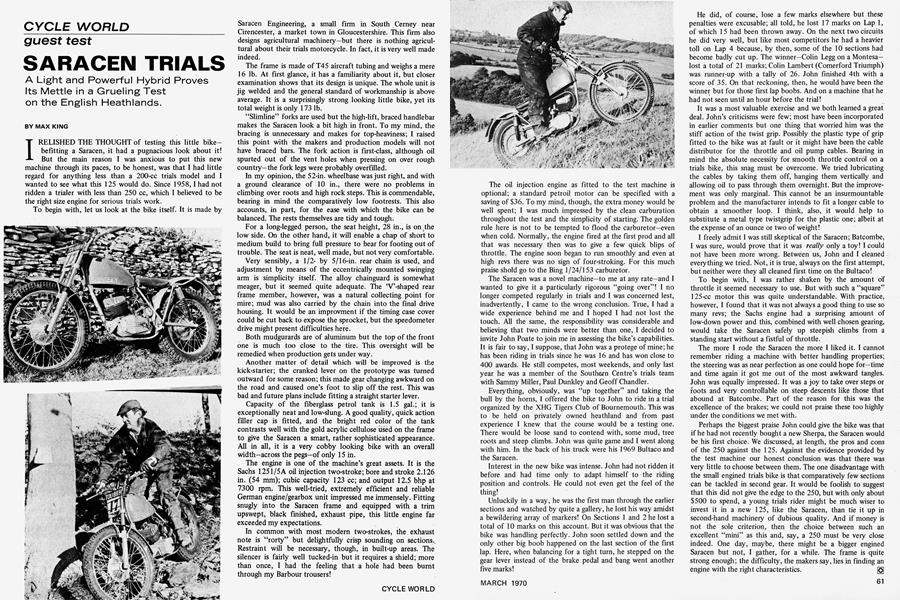

SARACEN TRIALS

CYCLE WORLD GUEST TEST

A Light and Powerful Hybrid Proves Its Mettle in a Grueling Test on the English Heathlands.

MAX KING

I RELISHED THE THOUGHT of testing this little bike— befitting a Saracen, it had a pugnacious look about it! But the main reason I was anxious to put this new

machine through its paces, to be honest, was that I had little regard for anything less than a 200-cc trials model and I wanted to see what this 125 would do. Since 1958, I had not ridden a trialer with less than 250 cc, which I believed to be the right size engine for serious trials work.

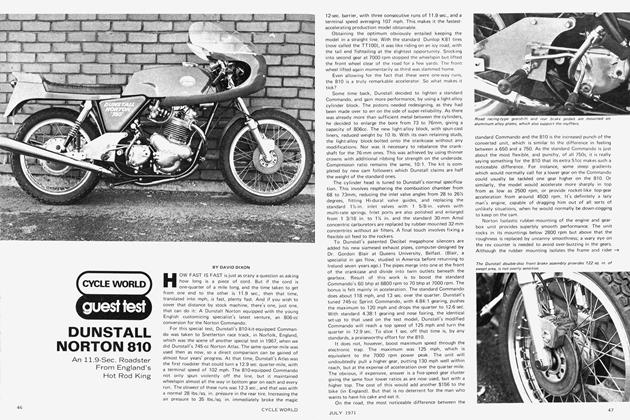

To begin with, let us look at the bike itself. It is made by Saracen Engineering, a small firm in South Cerney near Cirencester, a market town in Gloucestershire. This firm also designs agricultural machinery—but there is nothing agricultural about their trials motorcycle. In fact, it is very well made indeed.

The frame is made of T45 aircraft tubing and weighs a mere 16 lb. At first glance, it has a familiarity about it, but closer examination shows that its design is unique. The whole unit is jig welded and the general standard of workmanship is above average. It is a surprisingly strong looking little bike, yet its total weight is only 173 lb.

“Slimline” forks are used but the high-lift, braced handlebar makes the Saracen look a bit high in front. To my mind, the bracing is unnecessary and makes for top-heaviness; I raised this point with the makers and production models will not have braced bars. The fork action is first-class, although oil spurted out of the vent holes when pressing on over rough country—the fork legs were probably overfilled.

In my opinion, the 52-in. wheelbase was just right, and with a ground clearance of 10 in., there were no problems in climbing over roots and high rock steps. This is commendable, bearing in mind the comparatively low footrests. This also accounts, in part, for the ease with which the bike can be balanced. The rests themselves are tidy and tough.

For a long-legged person, the seat height, 28 in., is on the low side. On the other hand, it will enable a chap of short to medium build to bring full pressure to bear for footing out of trouble. The seat is neat, well made, but not very comfortable.

Very sensibly, a 1/2by 5/16-in. rear chain is used, and adjustment by means of the eccentrically mounted swinging arm is simplicity itself. The alloy chainguard is somewhat meager, but it seemed quite adequate. The ‘V’-shaped rear frame member, however, was a natural collecting point for mire; mud was also carried by the chain into the final drive housing. It would be an improvment if the timing case cover could be cut back to expose the sprocket, but the speedometer drive might present difficulties here.

Both mudgurards are of aluminum but the top of the front one is much too close to the tire. This oversight will be remedied when production gets under way.

Another matter of detail which will be improved is the kick-starter; the cranked lever on the prototype was turned outward for some reason; this made gear changing awkward on the road and caused one’s foot to slip off the rest. This was bad and future plans include fitting a straight starter lever.

Capacity of the fiberglass petrol tank is 1.5 gal.; it is exceptionally neat and low-slung. A good quality, quick action filler cap is fitted, and the bright red color of the tank contrasts well with the gold acrylic cellulose used on the frame to give the Saracen a smart, rather sophisticated appearance. All in all, it is a very cobby looking bike with an overall width—across the pegs—of only 15 in.

The engine is one of the machine’s great assets. It is the Sachs 1251/5A oil injection two-stroke; bore and stroke 2.126 in. (54 mm); cubic capacity 123 cc; and output 12.5 bhp at 7300 rpm. This well-tried, extremely efficient and reliable German engine/gearbox unit impressed me immensely. Fitting snugly into the Saracen frame and equipped with a trim upswept, black finished, exhaust pipe, this little engine far exceeded my expectations.

In common with most modern two-strokes, the exhaust note is “rorty” but delightfully crisp sounding on sections.. Restraint will be necessary, though, in built-up areas. The silencer is fairly well tucked-in but it requires a shield; more than once, I had the feeling that a hole had been burnt through my Barbour trousers!

The oil injection engine as fitted to the test machine is optional; a standard petroil motor can be specified with a saving of $36. To my mind, though, the extra money would be well spent; I was much impressed by the clean carburation throughout the test and the simplicity of starting. The golden rule here is not to be tempted to flood the carburetor—even when cold. Normally, the engine fired at the first prod and all that was necessary then was to give a few quick blips of throttle. The engine soon began to run smoothly and even at high revs there was no sign of four-stroking. For this much praise shold go to the Bing 1/24/153 carburetor.

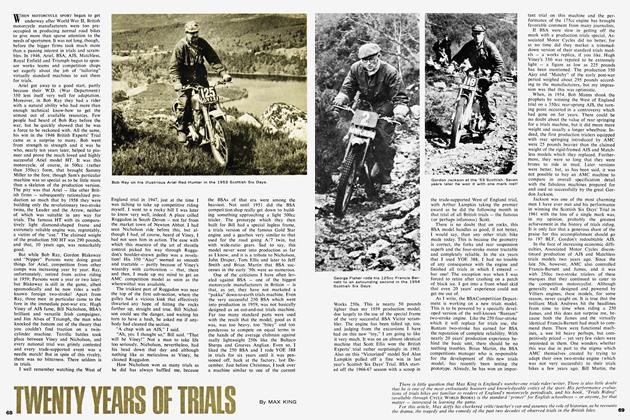

The Saracen was a novel machine—to me at any rate—and I wanted to give it a particularly rigorous “going over”! I no longer competed regularly in trials and I was concerned lest, inadvertently, I came to the wrong conclusion. True, I had a wide experience behind me and I hoped I had not lost the touch. All the same, the responsibility was considerable and believing that two minds were better than one, I decided to invite John Poate to join me in assessing the bike’s capabilities. It is fair to say, I suppose, that John was a protege of mine; he has been riding in trials since he was 16 and has won close to 400 awards. He still competes, most weekends, and only last year he was a member of the Southern Centre’s trials team with Sammy Miller, Paul Dunkley and Geoff Chandler.

Everything, obviously, was “up together” and taking the bull by the horns, I offered the bike to John to ride in a trial organized by the XHG Tigers Club of Bournemouth. This was to be held on privately owned heathland and from past experience I knew that the course would be a testing one. There would be loose sand to contend with, some mud, tree roots and steep climbs. John was quite game and I went along with him. In the back of his truck were his 1969 Bultaco and the Saracen.

Interest in the new bike was intense. John had not ridden it before and had time only to adapt himself to the riding position and controls. He could not even get the feel of the thing!

Unluckily in a way, he was the first man through the earlier sections and watched by quite a gallery, he lost his way amidst a bewildering array of markers! On Sections 1 and 2 he lost a total of 10 marks on this account. But it was obvious that the bike was handling perfectly. John soon settled down and the only other big boob happened on the last section of the first lap. Here, when balancing for a tight turn, he stepped on the gear léver instead of the brake pedal and bang went another five marks!

He did, of course, lose a few marks elsewhere but these penalties were excusable; all told, he lost 17 marks on Lap 1, of which 15 had been thrown away. On the next two circuits he did very well, but like most competitors he had a heavier toll on Lap 4 because, by then, some of the 10 sections had become badly cut up. The winner—Colin Legg on a Montesa— lost a total of 21 marks; Colin Lambert (Comerford Triumph) was runner-up with a tally of 26. John finished 4th with a score of 35. On that reckoning, then, he would have been the winner but for those first lap boobs. And on a machine that he had not seen until an hour before the trial!

It was a most valuable exercise and we both learned a great deal. John’s criticisms were few; most have been incorporated in earlier comments but one thing that worried him was the stiff action of the twist grip. Possibly the plastic type of grip fitted to the bike was at fault or it might have been the cable distributor for the throttle and oil pump cables. Bearing in mind the absolute necessity for smooth throttle control on a trials bike, this snag must be overcome. We tried lubricating the cables by taking them off, hanging them vertically and allowing oil to pass through them overnight. But the improvement was only marginal. This cannot be an insurmountable problem and the manufacturer intends to fit a longer cable to obtain a smoother loop. I think, also, it would help to substitute a metal type twistgrip for the plastic one; albeit at the expense of an ounce or two of weight!

I freely admit I was still skeptical of the Saracen; Batcombe, I was sure, would prove that it was really only a toy! I could not have been more wrong. Between us, John and I cleaned everything we tried. Not, it is true, always on the first attempt, but neither were they all cleaned first time on the Bultaco!

To begin with, I was rather shaken by the amount of throttle it seemed necessary to use. But with such a “square” 125-cc motor this was quite understandable. With practice, however, I found that it was not always a good thing to use so many revs; the Sachs engine had a surprising amount of low-down power and this, combined with well chosen gearing, would take the Saracen safely up steepish climbs from a standing start without a fistful of throttle.

The more I rode the Saracen the more I liked it. I cannot remember riding a machine with better handling properties; the steering was as near perfection as one could hope for—time and time again it got me out of the most awkward tangles. John was equally impressed. It was a joy to take over steps or roots and very controllable on steep descents like those that abound at Batcombe. Part of the reason for this was the excellence of the brakes; we could not praise these too highly under the conditions we met with.

Perhaps the biggest praise John could give the bike was that if he had not recently bought a new Sherpa, the Saracen would be his first choice. We discussed, at length, the pros and cons of the 250 against the 125. Against the evidence provided by the test machine our honest conclusion was that there was very little to choose between them. The one disadvantage with the small engined trials bike is that comparatively few sections can be tackled in second gear. It would be foolish to suggest that this did not give the edge to the 250, but with only about $500 to spend, a young trials rider might be much wiser to invest it in a new 125, like the Saracen, than tie it up in second-hand machinery of dubious quality. And if money is not the sole criterion, then the choice between such an excellent “mini” as this and, say, a 250 must be very close indeed. One day, maybe, there might be a bigger engined Saracen but not, I gather, for a while. The frame is quite strong enough; the difficulty, the makers say, lies in finding an engine with the right characteristics.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

March 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1970 -

Features

FeaturesDoes Your Club Owe Income Tax?

March 1970 By Robert O. Fee -

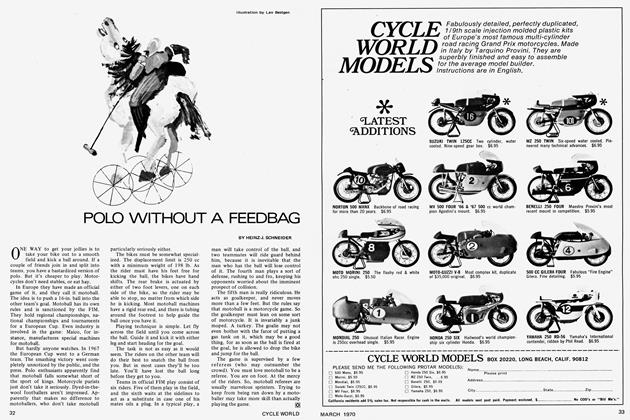

Competition

CompetitionPolo Without A Feedbag

March 1970 By Heinz-J. Schneider -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

March 1970 By John Dunn