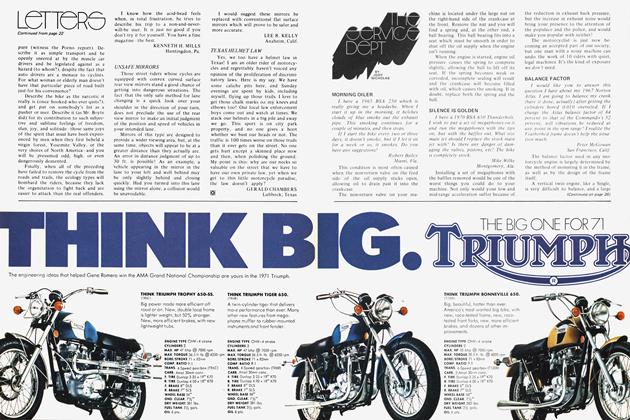

DUNSTALL NORTON 810

CYCLE WORLD guest test

An 11.9-Sec. Roadster From England's Hot Rod King

DAVID DIXON

HOW FAST IS FAST is just as crazy a question as asking how long is a piece of cord. But if the cord is one-quarter of a mile long, and the time taken to get from one end to the other is 11.9 sec., then that time, translated into mph, is fast, plenty fast. And if you wish to cover that distance by stock machine, there's one, just one, that can do it: A Dunstall Norton equipped with the young English customizing specialist's latest venture, an 806-cc conversion for the Norton Commando.

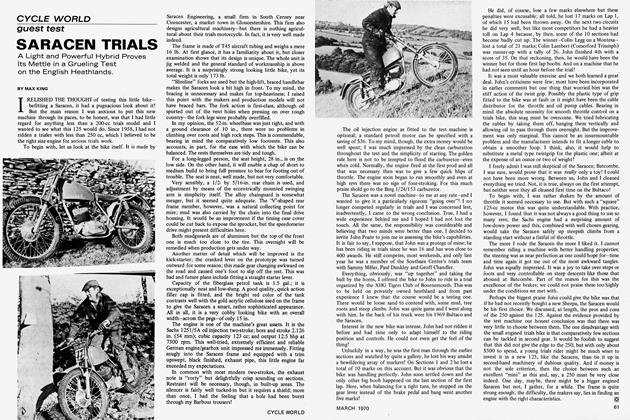

For this special test, Dunstall's 810-kit-equipped Commando was taken to Snetterton race track, in Norfolk, England, which was the scene of another special test in 1967, when we did Dunstall s 745-cc Norton Atlas. The same quarter-mile was used then as now, so a direct comparison can be gained of almost four years' progress. At that time, Dunstall's Atlas was the first roadster that could turn a 12.9 sec. quarter-mile, with a terminal speed of 102 mph. The 810-equipped Commando not only spun violently off the line, but it maintained wheelspin almost all the way in bottom gear on each and every run. The slowest of these runs was 12.3 sec., and that was with a normal 28 lbs./sq. in. pressure in the rear tire. Increasing the air pressure to 35 lbs./sq. in. immediately broke the magic 12-sec. barrier, with three consecutive runs of 11.9 sec., and a terminal speed averaging 107 mph. This makes it the fastestaccelerating production model obtainable.

Obtaining the optimum obviously entailed keeping the model in a straight line. With the standard Dunlop K81 tires (now called the TT100), it was like riding on an icy road, with the tail end fishtailing at the slightest opportunity. Snicking into second gear at 7000 rpm stopped the wheelspin but lifted the front wheel clear of the road for a few yards. The front wheel lifted again momentarily as third was slammed home.

Even allowing for the fact that these were one-way runs, the 810 is a truly remarkable accelerator. So what makes it tick?

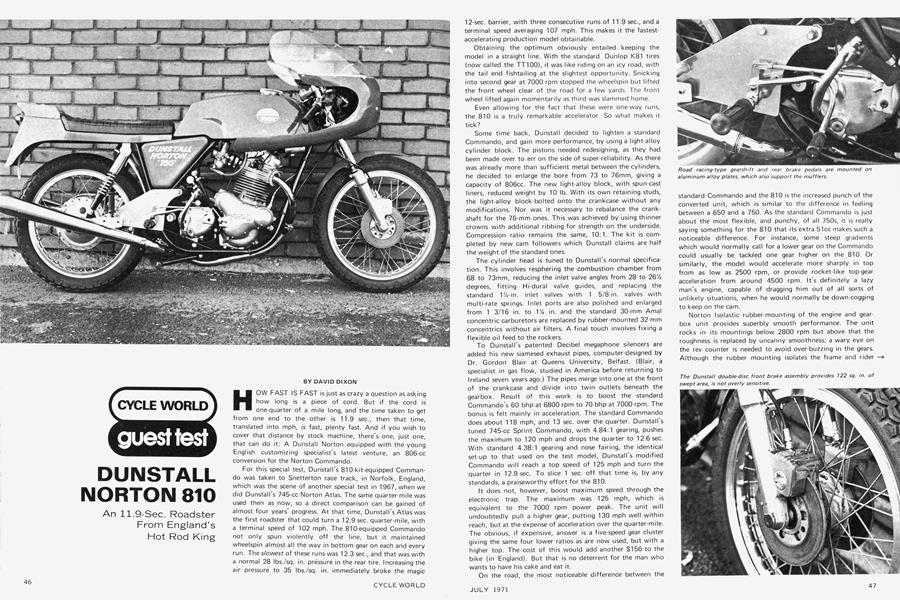

Some time back, Dunstall decided to lighten a standard Commando, and gain more performance, by using a light-alloy cylinder block. The pistons needed redesigning, as they had been made over to err on the side of super-reliability. As there was already more than sufficient metal between the cylinders, he decided to enlarge the bore from 73 to 76mm, giving a capacity of 806cc. The new light-alloy block, with spun-cast liners, reduced weight by 10 lb. With its own retaining studs, the light-alloy block-bolted onto the crankcase without any modifications. Nor was it necessary to rebalance the crankshaft for the 76-mm ones. This was achieved by using thinner crowns with additional ribbing for strength on the underside. Compression ratio remains the same, 10:1. The kit is completed by new cam followers which Dunstall claims are half the weight of the standard ones.

The cylinder head is tuned to Dunstall's normal specification. This involves resphering the combustion chamber from 68 to 73mm, reducing the inlet valve angles from 28 to 26V2 degrees, fitting Hi-dural valve guides, and replacing the standard 11/2-in. inlet valves with 1 5/8-in. valves with

multi-rate springs. Inlet ports are also polished and enlarged from 1 3/16 in. to VÁ in. and the standard 30-mm Amal concentric carburetors are replaced by rubber-mounted 32-mm concentrics without air filters. A final touch involves fixing a flexible oil feed to the rockers.

To Dunstall's patented Decibel megaphone silencers are added his new siamesed exhaust pipes, computer-designed by Dr. Gordon Blair at Queens University, Belfast. (Blair, a specialist in gas flow, studied in America before returning to Ireland seven years ago.) The pipes merge into one at the front of the crankcase and divide into twin outlets beneath the gearbox. Result of this work is to boost the standard Commando's 60 bhp at 6800 rpm to 70 bhp at 7000 rpm. The bonus is felt mainly in acceleration. The standard Commando does about 118 mph, and 13 sec. over the quarter. Dunstall's tuned 745-cc Sprint Commando, with 4.84:1 gearing, pushes the maximum to 120 mph and drops the quarter to 12.6 sec. With standard 4.38:1 gearing and nose fairing, the identical set-up to that used on the test model, Dunstall's modified Commando will reach a top speed of 125 mph and turn the quarter in 12.9 sec. To slice 1 sec. off that time is, by any standards, a praiseworthy effort for the 810.

It does not, however, boost maximum speed through the electronic trap. The maximum was 125 mph, which is equivalent to the 7000 rpm power peak. The unit will undoubtedly pull a higher gear, putting 130 mph well within reach, but at the expense of acceleration over the quarter-mile. The obvious, if expensive, answer is a five-speed gear cluster giving the same four lower ratios as are now used, but with a higher top. The cost of this would add another $156 to the bike (in England). But that is no deterrent for the man who wants to have his cake and eat it.

On the road, the most noticeable difference between the standard Commando and the 810 is the increased punch of the converted unit, which is similar to the difference in feeling between a 650 and a 750. As the standard Commando is just about the most flexible, and punchy, of all 750s, it is really saying something for the 81 0 that its extra 51cc makes such a noticeable difference. For instance, some steep gradients which would normally call for a lower gear on the Commando could usually be tackled one gear higher on the 810. Or similarly, the model would accelerate more sharply in top from as low as 2500 rpm, or provide rocket-like top-gear acceleration from around 4500 rpm. It's definitely a lazy man's engine, capable of dragging him out of all sorts of unlikely situations, when he would normally be down-cogging to keep on the cam. from vibration, it does nothing for the unit itself. This was demonstrated dramatically by a previous Commando engine's inability to rev above 6000, due to frothing of the fuel caused by excessive engine vibration. Dunstall fits his carburetors on rubber pipes but found that the length of the rubber is critical, otherwise the carbs oscillate violently on the rubber above 6000 rpm. The ideal length is with the two metal stubs, upon which the rubber is clamped, to be almost—but not quitetouching one another.

Norton Isolastic rubber-mounting of the engine and gearbox unit provides superbly smooth performance. The unit rocks in its mountings below 2800 rpm but above that the roughness is replaced by uncanny smoothness; a wary eye on the rev counter is needed to avoid over-buzzing in the gears. Although the rubber mounting isolates the frame and rider —»

Flexible though the engine is, the 81 0's gearbox is there for using, and no more delightful a gear shift is made anywhere. Light, short and crisp in movement, the gear pedal linkage is well suited for rapid cog swapping. Bottom gear, at 11.2:1, is sufficiently low for all normal uses, with a relatively big gap between bottom and second, but compensated for by three closer ratios higher up. Third is sufficiently high to better 100 mph with ease.

Moderately light and sensitive in operation, the standard Commando clutch proved completely impervious to abuse. It withstood 20 full-throttle standing-starts without any trace of overheating, and did not require adjustment at any time.

Roadholding and steering are more taut than on the standard Commando. Rear springs of heavier poundage cut out wallowing, which seems to be characteristic of previous Commandos. Front fork action was stiffer because the standard SAE 20 oil had not been replaced by a multi-grade for the cold weather encountered during the test. This stiffening of the suspension made the machine uncomfortable at normal road speeds. But on the track, the story was entirely different; the taut suspension provided racer-like roadholding and steering. The only occasion the rear end showed any tendency to fishtail was on the undulations of the 100 mph left-hander into the main (Norwich) straight, and the fishtail was virtually cured by jacking up the units to their hardest position.

By using a 3.60-19 in. Dunlop K81 front tire (now called TT100), the 40-mph front wheel shimmy characteristic of all standard Commandos sampled by this tester has been cured. The grip provided by the tires is superb, allowing the machine to be heeled over until the legs of the center stand touch down. With the stand removed, nothing touches down. On wet roads, the tires' grip is truly phenomenal and ample warning of impending slides is provided. Even when the rear tire does break away, it does so gently and the drift is easily corrected.

The riding position afforded by the rear-set footpegs and clip-on handlebars is a semi-racing crouch which is comfortable for blasting along open roads, but not so relaxing for town travel. Too much weight is thrown onto the rider's wrists, and after a time this becomes tiresome. The nose-fairing fitted to the test model provides adequate protection for the upper half of the rider's body and also deflects cold air, and some rain, away from the hands.

Dunstall's hydraulically operated twin-disc front brakes are a necessity for a machine possessing the potential of this one, especially if a passenger is carried. Only moderately light in operation, the brakes seem to have less than average power when applied gently below 30 mph. But when the lever is applied hard in conjunction with the rear, as when taking the stopping figure, the hydraulic operation of the friction pads provides effortless stopping. Although the 23 ft., 9 in. stopping distance may seem impossibly short, it was achieved with remarkably little fuss, and no front wheel locking. Nor was the rider in immediate danger of being catapulted over the top of the screen! And the brake is sufficiently sensitive to allow much more potent stopping on wet surfaces than with a conventional drum brake.

In normal conditions, fuel consumption averaged between 55 and 60 mpg (imperial gallon). This dropped to just under 50 mpg when the unit was driven hard over long distances. And hard driving also worsened oil consumption—one pint was used every 300 miles.

With its bright red finish nicely offsetting the polished chromium plating and light-alloy parts, the 810 is an eyecatching mount. That it lives up to its looks can be seen from a glance at the performance figures. But its greatest charm is its superb flexibility and top-gear performance. ¡0

DUNSTALL

NORTON 810

SPEC I FICATIONS

$1770

PERFORMANCE