The Hour Record

DAVID DIXON

LONG DISTANCE record breaking is like bashing one's head against a wall — it's lovely when it stops. At latest, this particular record had to stop at one hour with, preferably, 120 or more miles tucked away between start and finish.

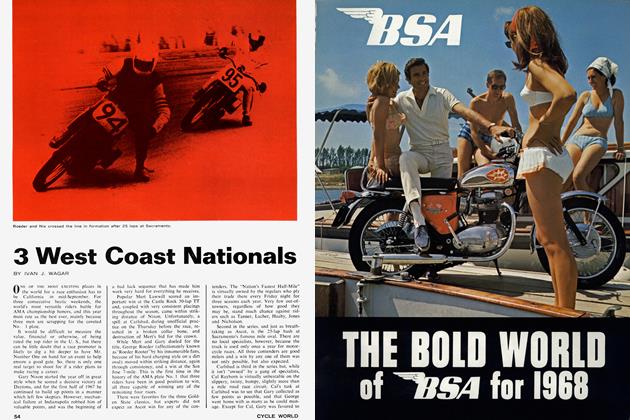

It was Paul Dunstall's idea. The 750 cc world one-hour record had stood since 1961 to Englishman George Catlin, who had put 111.046 miles into 60 minutes at Montlhery, France, in the course of a 24-hour bid with a BMW R69S and a team of riders. The absolute one-hour record stands to Mike Hailwood (499 MV Agusta), who achieved 144 mph at Daytona in 1964.

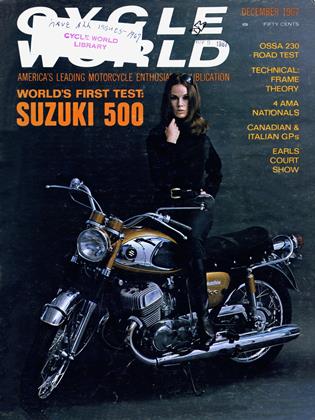

Last fall, Dunstall made two unsuccessful attempts. The first one, in pouring rain at Monza, saw Griff Jenkins reach within seven minutes of the hour at an average of 125 mph when distortion from the water thrown back from the front wheel caused the cylinder block to crack.

A few weeks later, at Earls Court, Paul asked me to ride a second Dominator, on which to partner Griff. This time, with two bikes, the London customizing specialist was taking no chances. I was to try to average approximately 120 mph, which should be well within the bike's capabilities (though I had reservations about it being within mine). Then Griff would go out and knock heck out of whatever I achieved, though he might blow the engine in his effort, in which case the record would be down to Dixon.

Sitting on the bus on my way to London Airport one frosty December morn, I saw a little news flash on the back page: "Two Britishers hurt near Turin, Italy, when a van capsized on their way to Monza race track." I could hardly get through the airport mob to the departure lounge quickly enough. There was Paul, calm and urbane as ever, with his music-composer brother, Ernie, and Paul's Italian agent, Italo Berigliano.

No time for niceties, the flight had been called. Thrusting the paper under Paul's nose, I gabbled, "Ring me if the bikes are okay and I'll fly out later." Dumbstruck for once, Paul and Italo headed for Italy, while Ernie and I returned to London. Those who think a blind around a highspeed, steeply banked bowl is no problem at all should be quickly disillusioned. At Monza, it's murder! The track has sunk badly in places on the banking, and the repairs have been worse, if anything, than the original damage. Even walking or driving slowly around, one can see, and feel, the undulations. At 130-140 mph, they heave the bike into the air, bottom the suspension, squash the tires, and play havoc with the rider's kidneys, teeth, head, arms and legs, so that he scarcely knows whether he is standing on his head or his toes.

The van was a write-off. Both bikes and rider were bent, and the project was shelved, permanently, I thought, until one day, last August, that quiet voice casually remarked, "Ready, then? We go in four weeks' time."

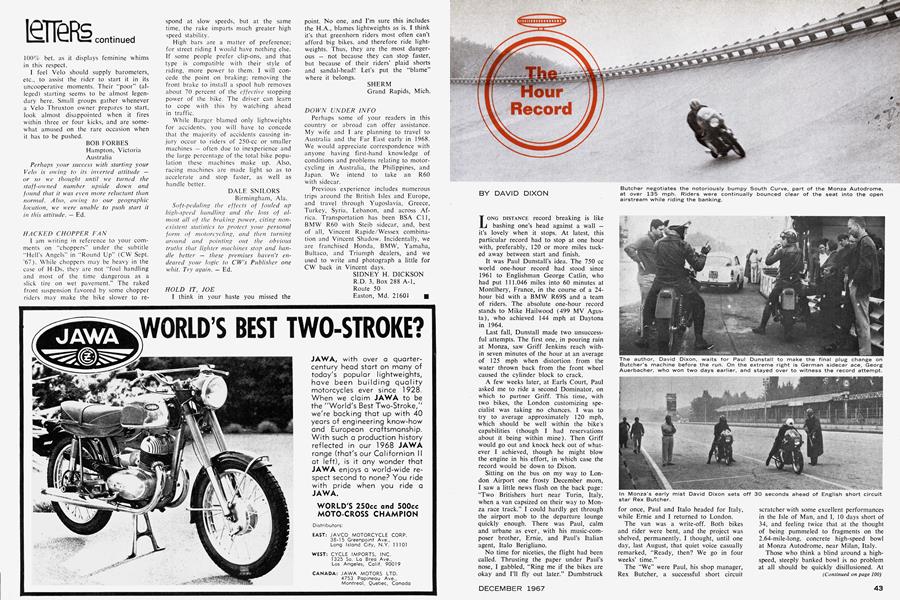

The "We" were Paul, his shop manager, Rex Butcher, a successful short circuit scratcher with some excellent performances in the Isle of Man, and I, 10 days short of 34, and feeling twice that at the thought of being pummeled to fragments on the 2.64-mile-long, concrete high-speed bowl at Monza Autodrome, near Milan, Italy.

(Continued on page 100)

Tucking the head under the screen is just asking for a Cassius Clay — sorry, Muhammed Ali — uppercut as the tank clobbers the rider's chin. As the bike flies down into a hollow, the rider's head flies up into the 130-mph draft and buffeting threatens to tear it off — that and the whiplash effect of hitting another succession of fiendish, spine-jarring bumps.

Even if the rider felt so inclined, he must not, cannot shut off, for the throttle is hard against the stop, and the hand clamped round it is hanging on for dear life itself.

Anyway, our group came for a record, not a Sunday jaunt, and the aches, pains and discomfort would have to wait.

Concentration required for record attempts is every bit as intense as in road racing, because saving time is just as important — even more so, for lost moments cannot be recovered at the next corner — and there is a definite "line" to be followed. I found in practice that on the yellow guide line, or two feet above it, gave the least agony. The ideal, the shortest possible path, was close in around the bottom where Rex tried to go, sometimes successfully. But my first big attack nearly finished me, as I lacked Rex's friction steering damper which he'd fitted, in addition to the hydraulic one, and the ensuing thisaway-thataway-straighten-up-youson-of-a-gun oscillation had me halfway up the banking before I'd recovered control. So I settled for the lazy way out and stuck to my own groove.

Oddly enough, the one thing which did not worry Rex, nor me, was diving into the banked turns at full rattle, about 144 mph for Rex, and 137 mph for me. Both turns are of very wide radius, their combined lengths forming almost half the track length, but they are also completely blind, so a rider cannot see around them. Of course the track was booked exclusively for the two of us, but supposing that deaf old Italian who lumbered off with that tractor and trailer 10 minutes before we started out was sweeping up leaves, and decided to take a short cut? My patron saint has been pretty good so far, but for this occasion, another couple were co-opted, just in case.

One of them had the sense to warn me, after 35 minutes, that the pistons were expanding as I came off the banking, so I whipped in the clutch and coasted a few hundred yards. It's amazing how far a bike can coast from that speed. Still doing about 100 or so, I gingerly fed in the clutch, the engine fired and, rather weakly, picked up steam again. But the edge had definitely gone, and I was 200-400 rpm down on my previous 6000 maximum.

In spite of chinning the tank top harder than ever, and trying to tighten the line, my times increased by two seconds per lap, and my average slumped from about 123 mph to nearer 121 mph. The going before had been fun compared with now. This was a crisis, and failure seemed imminent, so a delicate sense of feeling suddenly became a dire necessity. All sorts of horrible noises were heard, felt, dismissed as imagination, re-heard, re-felt, and relived. Nothing else mattered now but to finish, whatever the cost.

Paul, hanging out lap time signals every lap, was worried, too. I could see him, hand cupped to ear, listening for a misfire, for any clue as to what might be the trouble. Sure enough, I could feel a misfire. Yes — definitely this time, no guessing. There was a slight falter, and revs peaked at 5600-5800, no higher.

Just after he held out the "5 minutes to go" sign, the engine died, slowly, but very definitely. There was no rattle, crash or grinding, just a gentle graceful loss of power, as if she'd had her life. Her stint was over. So was mine. A wave of numbness engulfed me as I coasted, still flat on the tank and very, very weary now, back around the banking toward the finish.

As I coasted to a halt, all hands waved me to the line. I pushed, a hand held me back till Butcher flashed past into his last lap, and I wearily pushed over to finish. Apparently, Paul's "5 minutes" sign was a few minutes adrift, and the engine expired just as the final minutes of my hour were up! It had only cost me about one lap.

As the timekeepers huddled over their watches, Rex roared in, grubby nosed, weary, but cheery as a sandboy. He knew the record was his, for he'd been lapping 2 or 3 seconds faster than I throughout, even faster when I struck trouble, and he only had to finish to claim the lot.

Then came the news — both of us had handsomely beaten the old hour figure. Rex had averaged a shattering 126.7 mph, and I'd done 119.7. And, a nice present, both of us also had belted the 10-km and 100-km figures for the class. These had stood for nearly 40 years!

Later we discovered that my cylinder head gasket had blown; it had probably started going when the engine first tightened. Rex's bike, however, had never missed a beat, had been revving throughout around the 6500 mark on the straights. This wasn't bad for fully equipped road bikes. ■

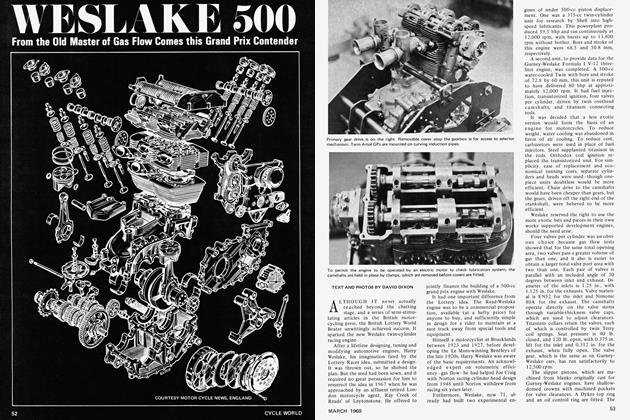

THE MACHINES 1967 745 cc Dunstall Dominators: alterations from standard — six-gallon petrol tanks, racing seats, 1968 fairings, Dunlop triangular racing tires inflated to 45 psi front and rear. THE RECORDS — 5 SEPTEMBER 1967. 10 Km: 120.785 m.p.h., Rex Butcher. Old record: 108.12 m.p.h., Jack Williams (598 Raleigh), 1929. 100 Km: 126.882 m.p.h., Rex Butcher. Old record: 107.71 m.p.h., Bert Denly (588 Norton), 1928. 1 Hour: 126.7 m.p.h., Rex Butcher. Old record: 111.046 m.p.h., George Catlin (587 BMW), 1961. Fastest lap, Rex Butcher, 129.4 m.p.h.