AMERICAN TRIALS PRIMER

MICHAEL BISHOP

DENIS MURPHY

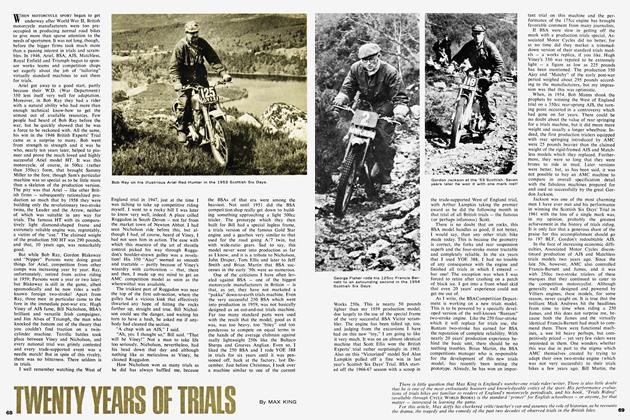

IF WE WERE ASKED to speculate about the reasons for the current growth of observed trials competition in the U. S., we would reply that it can be attributed to the growth of motorcycling sports in general, and we don’t dodge into this niche because it is quick or convenient; interest in competitive motorcycling has grown tremendously. Understandably, not everyone who rides a motorcycle for fun is interested in making the commitment to speed competition. Well, then, what else is there that tests a rider’s ability and the worthiness of his machine? Why trials, of course.

Trials, alternately called English trials and observed trials, demands its very own brand and degree of commitment. The risks to the human anatomy and to machinery are not as great as they are in the speed sports. The personal triumphs and the frustrations, however, are another matter. The trials rider isn’t permitted the luxury of blaming his performance on a bad start, or lack of horsepower, or interference from another rider. In most trials events he is never pressed for time, nor is he required to overstress his bike, nor is he bothered with wheel-to-wheel contests. His arch rival is the rider he himself was last week.

Trials courses are characterized by variety — from one section to another, from one course to another and from one week to the next, depending on the weather. But, in one sense, good courses are consistent — they are always terrible things to ride, and the name of the game is skill.

A great deal has been written about trials riding, but very little has been published in this country because of the previous lack of interest. For this article, we have been able to rely a great deal on first-hand experience gained through several years of active trials riding, and we present our case from machine selection and preparation, through riding technique, to planning and laying out a trials course. And, if we generate a bit of interest among our readers through the telling, so much the better.

MACHINE SELECTION AND PREPARATION

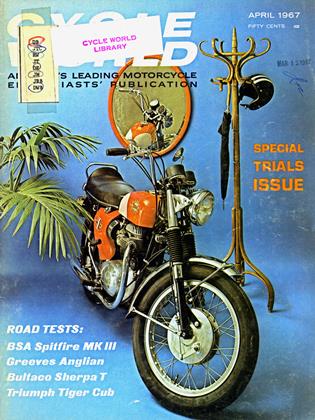

Currently, there are some half-dozen trials models available in this country, and as might be imagined, they encompass features that are desirable for the duty for which they are intended. It would be a simple matter at this point for us to say that you should try each one and decide for yourself; but we would first have to assume that you were prepared to spend from $600 to $900 for a special one-purpose machine. Instead, let’s pursue a more reasonable line, analyzing the makeup of a good trials mount, that will equip the would-be trials rider with a set of guidelines which will enable him to evaluate any motorcycle with regard to its potential trials worthiness.

Chassis geometry is as good a place as any to start. A trialer should have a noticeably steep head angle to permit the front wheel to be turned from lock to lock with only a minimal center-of-gravity shift. All this means is that the height of the motorcycle, measured from the top of the fuel tank, say, should not be significantly greater with the wheel in the straight-ahead position than it is when the front wheel is turned to either right or left lock, nor should the steering head move significantly from side to side. The reasoning behind this matter becomes obvious when we consider an undesirable extreme — shallow head angle. With shallow head angle, the up and down and side-toside movement of the motorcycle is very noticeable, both visually and in steering “feel,” with the bike seeming unstable at any position other than one of the two locks. When the bike is being ridden, this condition causes the bike to “flop” in the direction it is being turned and, consequently, destroys steering precision. A further consideration for steering is that steering lock should be extreme, on the order of 150 to 160 degrees from lock to lock.

Because high-speed stability is not a consideration for a trialer, wheelbase can and should be relatively short to afford the bike a short turning radius and good traction potential. Suspension should have long travel and be soft; short, stiff suspension tends to respond to all surface irregularities with a resultant choppiness that both destroys steering precision and disrupts the rider’s concentration. Typically, tires on a trialer will be knobby or designed specifically for trials. They should be inflated to a very low pressure — four to ten psi — and should have sufficient side-wall strength to retain their shape at low pressure.

Low weight is as important to a trialer as it is to a scrambler or road racer. It may be argued that it is even more important, because the speed — or lack of it — in trials does not impart the inherent stability gained from inertia and wheel rotation, and at a slow rate of progress, a heavy motorcycle is cumbersome and reluctant to do much more than lie down. While it can be controlled and herded along, the effort required to manage a heavy bike is tiring and would be better spent coping with the uncivilized aspects of the course. There is no firm rule for weight, but an average-sized rider would do well to work toward a motorcycle wet weight of around 200 pounds for a 250class machine. There is little question that a principal factor in the popularity of the two-cycle engine for trials is the low weight inherent in this scheme. In addition, the greatest concentration of weight in a two-cycle relative to a four-cycle, is at the bottom, which further enhances the handling of a trialer in that it provides a lower c.g. with a resultant reduction in top hamper — top weight which seems to grow to unmanageable proportions as the bike is leaned increasingly to either side of the vertical axis. Other factors affecting top hamper, or top heaviness, are fuel tank size and weight; seat size, weight and height; fender type; the presence or absence of an oil tank; exhaust system, or any other bits mounted high on the bike. When the components affecting top hamper are correct, they offer the rider an additional benefit in that the bike will have a comfortably narrow riding position, the legs can be kept parallel and knee grip can be obtained.

TRACT ABILITY

At first glance, it might appear that the engine of a potential trialer deserves little more concern than whether or not it runs. Granted, we are not looking for groundshaking power output like that sought for a scrambler. In fact, this would more often than not prove detrimental to trials riding because it is invariably accompanied by “pipey-ness” or “cammy-ness” which make power application anything but predictable. A good trials engine should be in a fairly soft state of tune. That is, compression ratio should be low or at least moderate; carburetor choke size should be small, so that intake velocity will be high enough at low revs to permit the engine to pull smoothly with slight changes in throttle opening (an engine that requires constant “clutching” and “cleaning out” is a hindrance); the flywheel should be heavy and, consequently, flywheel effect should be pronounced, so that the engine will run contentedly from one widely spaced beat to the next at low revs; the exhaust system should be fairly restrictive, both to soften the state of tune and to quiet the exhaust as much as possible — a loud, penetrating exhaust note is one of the most effective concentration destroyers imaginable; and, finally, the overall gear ratio for bottom gear should be quite low — about 20:1 for a 350 or 500, 24 to 28:1 for a 200 or 250 and 30 to 32:1 for a 100 or 125.

The ideal transmission arrangement, occasionally referred to as “trials layout,” will have first and second gears spaced closely, with third a bit distant and fourth gear noticeably “tall.” Fortunately for the trialsman, many dual-purpose, sports, and trail bikes come with widely spaced gearing that closely approximates good trials layout. The most important consideration, however, is the overall ratio for low gear, and this can usually be simply attained through the use of a good rear-wheel accessory sprocket of the desired size or with an alternate countershaft sprocket which some motorcycle manufacturers offer for their products.

RIDER COMFORT

For a frame of reference for rider comfort we’ll start with the standing position — the attitude in which a trialsman spends most of his time. It is the basis for good trials form and merits prime consideration for selection and preparation of a trialer.

Generally, the standing position, with the motorcycle on level ground, should be neutral; the rider’s weight should be mostly on the pegs and only a small percentage of it on the handlebars. He very definitely should not have to hold himself forward with the handlebars, and this will be the case with most machines not tailored for trials. The cause and cure, happily, are simple; you must hold yourself forward because the pegs are too low and too far forward. Relocating the pegs up and back several inches, about 45 degrees from the original position, will usually correct the problem. In addition to correcting the standing position to be more comfortable with this modification, you will have gained two very important control characteristics: you have raised your c.g. relative to that of the bike, and have thus increased your moment — or advantage. By this we mean that your movements from side to side will have a desirably greater effect on the vertical attitude of the bike. In short, you now have more leverage to enable you to make the bike do what you want. Secondly, you have increased your traction control potential by placing the pegs nearer to the rear axle. Thus, when you hike out over the rear wheel, the transfer of weight will be more pronounced than it would have with the pegs in the original position. Also, with the pegs in their new position, when you lean forward to hold the front end down on steep climbs or unweight the rear wheel to permit it to break traction when you are in danger of running out of power and bogging the engine, you will get an honest transfer of weight, where before you were more than likely unweighting the front end by pulling on the bars to bring yourself forward.

Let’s now explore what might well be called the “Great Handlebar Controversy.” This is the motorcyclist’s sacred cow — a matter in which even the slightest suggestion from the closest of comrades constitutes an infringement of personal freedom. Trials, like all the other forms of motorcycle sport, is not without its handlebar mystique, and like the other forms it, too, has its ground rules that the tyro would do well to follow before attempting to apply his personal preferences.

First, trials handlebars should be relatively flat, not rising much more than an inch or so from the steering head, and they should be almost perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bike. Logically, more than traditionally, trials bars are somewhat long, and the reason is quite simple: because we are using a flat, straight bar that pulls us forward and nearly in line with the steering axis, we find that a conventional bar width would cause us to “bottom” our hands on the tank. Therefore, we select a wider bar — about one handspan on either end — that will permit maximum steering lock without smashing a hand against the fuel tank. A further benefit is gained in that we will have increased steering leverage with the wider bars.

The controls of a trialer can do much to make your ride pleasant or unpleasant, but we shall concern ourselves with the positive side of the issue and determine what is necessary to make trials riding pleasant.

The clutch is going to see about as much duty as anything else in trials. Therefore, the lever should require only a moderate amount of pressure to disengage the clutch because it will be used as frequently, and as deftly, as the throttle. Pressure, of course, should be light to keep the rider from wearing out his left hand and not cause clutch control to be confused with bar control. Ideally, the clutch control should be able to be operated with the first two fingers and should be adjusted so that it is fully disengaged when it rests comfortably atop the third and fourth fingers, which should never leave the handgrip. Like clutch control, front brake control should be independent of handlebar’s steering function.

The throttle control should be the normal half-turn type adjusted with no more than about 1 /32-inch of slack. The reason for staying away from a quick-turn throttle is obvious: surprises are unwelcome in this game.

With regard to foot controls, there is only one point to be kept in mind: they should be operative without moving either foot from the pegs. This is particularly obvious for the rear brake, but possibly not so for the gear selector. That the gear selector is given little consideration is amply evidenced by some of the trials bikes we have tested that have required the gear changing foot to be moved forward to engage the selector arm. It is perhaps a debatable point that gear changes should be simply accomplished, since they are so rarely desired, once underway in a section. But, we find that they are invariably needed — theory be hanged — at the most inopportune times when energy must be concentrated on keeping the bike within the boundaries of a very difficult section. Gear changes in these moments should not be unnecessarily complicated by a double-shuffle routine to bring the rider into the area where the end of the selector might lie.

Our final point concerning the placement of foot controls might seem a bit odd; but until you have ridden trials for a time, it’s unlikely that you will encounter the situation that dictates that your starter lever be accessible to you while you are moving either forward or backward with both feet on the pegs. It is easily imaginable that it would be necessary — at some rare moment — to restart your engine after you are underway, with your feet on the pegs and without losing forward direction. But — and this is for the truly serious trialsman — we know of an instance in which a trials rider inadvertently killed his engine on a steep and slimy ascent, slid back down without touching foot to ground, restarted his engine and ascended once more to “clean” the section without so much as a dab!

The matter of seat or saddle comfort for a trialer involves characteristics that differ greatly from those found in other types of motorcycles. A trials seat should be small, both in width and height, and because it will get very little use, it need not be amply padded. Also, it should be mounted low enough that when the rider is sitting on it, both of his feet are firmly on the ground with the knees slightly bent so that he can find the greatest amount of grip when footing. It’s much better to lose three marks for footing than to lose five for stopping, when you can’t paddle your way through a section because the seat is too tall.

RIDING TRIALS

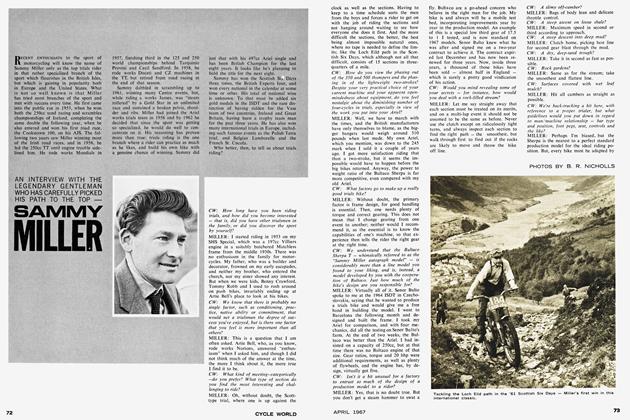

Now we come, finally, to an explanation of what the standing position is all about. The standing position offers infinitely more control than does a sitting position for several reasons. Weight transfer for traction and balance is more easily accomplished; the rider’s movements have a greater effect on the attitude of the machine because of his increased moment; the bike rolls more freely over obstacles because it doesn’t have to displace all of the rider’s weight, as it would if he were sitting on the seat; and it is less tiring to the rider to permit the machine to move about beneath him, rather than accompanying it with each and every move.

The riding problems facing a trialsman are widely varied but generally composed of one or several elements. Let’s, then, take a look at the fundamental problems and see how each should be handled.

Ascents. Climbs should always be carefully assessed before being attempted with regard to traction surface and the nature of the hill (cuts, ledges, turns, etc.). Climbs should be tackled in as high a gear and with as much speed as possible. Make certain that your approach is neat — clean, in control, and in a straight line — because if you start your climb a little out of shape, it’s unlikely that you will be able to recover, but instead will probably find yourself in increasing trouble as you progress.

Descents. As with ascents, descents should be carefully assessed before being attempted, with particular attention paid to the outrun (turns, bumps, ditches, etc.). Front brake control plays a major role in negotiating downhills; most of the weight will be transferred to the front wheel, making the unladen rear wheel prone to locking when the rear brake is applied. This frequently results in a dead engine and a rear end that is trying to get to the bottom before the front. Much of the difficulty can be eliminated from descending by the use of a compression release, found on most trials bikes or easily fitted to engines that are not so equipped. If your downhill progress is interrupted by a turn, front brake pressure should be released during the turn and then reapplied after the turn has been completed. Rocks. Pick a path, then be aggressive and purposeful — but temperate. Assault the larger ones head-on, moving back to lighten the front wheel as it contacts the rock, and then forward to unweight the rear wheel as it passes over.

Mud. The key to riding mud, particularly when it is deep, is momentum. Mud must be entered with as much speed as is possible, because it offers virtually no traction and will, in fact, resist the front wheel. What little traction there is can be further increased by pulling as high a gear as possible.

Leaf Mulch. Like mud, leaf mulch — particularly when it is wet — offers little traction and must therefore be ridden with momentum. Be careful with turns, however, because this surface offers very little side resistance to a tire.

Sand. Not nearly so treacherous as mud and leaf mulch, sand is very quickly mastered. Traction is considerably improved, yet momentum is still essential. Sand offers moderate steering potential but the reaction will be delayed.

Streams. Rocky streams should be ridden with great care; the tops of rocks are usually slippery and optical diffraction has them turning up much sooner than expected. Sandy streams offer few problems because the stream bottom compacts and provides good traction. Watch out for occasional rocks, however.

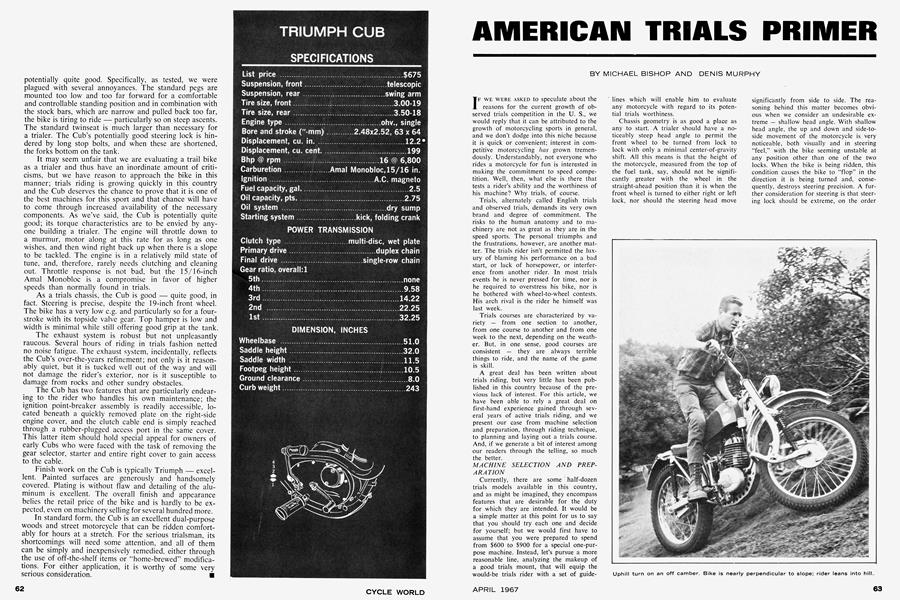

Off Cambers. All this amounts to is riding perpendicular to the fall-line of a slope. To properly accomplish this we must break ourselves of a bad and common habit — keeping the machine perpendicular to the horizon. Instead, the machine should be kept perpendicular, or nearly so, to the fall-line. This means that the rider will be uphill of the bike, which at first seems unsound. When the machine is kept straight up, the rear wheel tends to slide downhill and the front wheel will seem to hang on; but this is only because we are forcing it to do so. With the machine leaned out from the hill, the rear wheel tends to hang on and the front wheel attempts to roll downhill. We know, however, that the front wheel can be controlled, so we are in effect making a simple tradeoff that will allow us to negotiate an off-camber path.

SECTION AND COURSE LAYOUT

Planning and laying out a trials course can be almost as much fun as riding the course. A really good trials course will have one distinguishing characteristic — variety. Ideally, it will progress up and down, in and out of mudholes, crisscrossing sandy washes and streams, and skirt off-camber hills and knolls. The course should utilize natural obstacles as far as possible, and it should go somewhere, such as in a large loop of several miles. Extremely tight “circus-act” sections can be employed but should not be overdone. If possible, complex sections, made up of several observed sub-sections, should be employed, because they allow the rider to relax and regroup his resources after negotiating a particularly difficult section before he must tackle the next. Observed sections should be linked with easy trails or roads that will permit riders to increase their speed and blow off steam while not being psychologically hampered by the critical eye of a section observer.

After a specific section has been laid out, and before it is marked, it should be tested by several riders involved with course planning to determine if the section can be ridden cleanly. It may take numerous attempts on particularly tough sections, and if it becomes apparent after a time that the section is impossible, it should be modified or even discarded. Observed sections should not be easy, but neither should they be so tough that they cause competitors to lose interest in them because they know they can’t be ridden cleanly.

The side boundaries of observed sections should be marked with either lime or tape, and tape is preferred. Section widths should be reasonable for all size motorcycles, and particularly difficult sections should allow even greater latitude so that each rider can pick his own path — within reason, of course. Transition roads and trails between observed sections should be marked with ribbon, lime or cards. Approaches to observed sections should be clearly marked to permit riders to prepare for what’s ahead. Also, markers announcing that an observed section begins, and ends, should be unquestionably clear.

One of the most difficult aspects encountered in staging a good trials is having enough observers. It is frequently possible to find more than enough “bodies,” but this isn’t really sufficient; they must be knowledgeable and trained. Fortunately, observers can be trained in a very short time. They should have a thorough understanding of the sport and must, of course, know what to look for — prods or dabs, footing, staying within the boundaries, stopping — and should never assume that a local ace will “clean” their section, no matter how easy it may be. Observers should be well cared for. They shouldn’t be expected to handle a section alone, but should be paired with another observer so they can spell each other. They should be provided with food, hot or cold drinks, and other rewards like small trophies, such as one association gives to its observers.

Different grading systems have been used from time to time, and the best of these is the widely used 1-3-5 — one mark lost for a prod or dab, three marks lost for two or more dabs (footing), and five marks lost for going out of bounds, stopping, falling, or refusing or failing to ride a section. A rider who negotiates a section without putting either foot down, without stopping and within the boundaries of the course, loses no marks and has “cleaned” the section.

At the end of the meeting, after all of the observers’ cards have been collected and the scores recorded, the rider with the least marks lost is declared the winner. In the event any two or more competitors have tied, the tie can be decided either on the basis of most number of sections ridden clean, or one section can be ridden as a tie-breaker.

In this treatise on observed trials, we have endeavored to present a broad case that is sufficiently informative to provide you with the basic knowledge for participating in the sporty but not one so confining that you feel you have no latitude. One of the greatest appeals that observed trials holds for the rider is that it is a very personal sport — from selecting and preparing your machine to bettering your performance every time you compete.