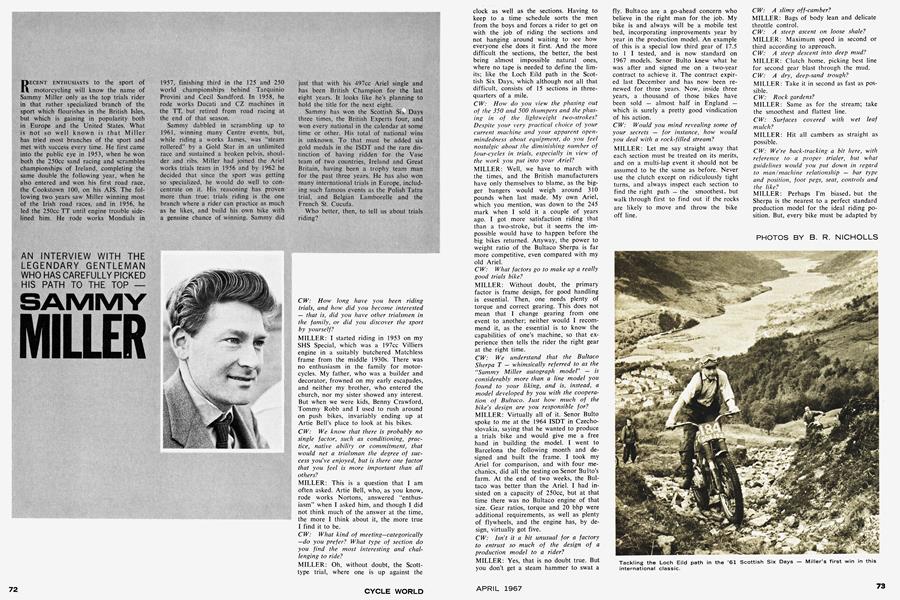

SAMMY MILLER

AN INTERVIEW WITH THE LEGENDARY GENTLEMAN WHO HAS CAREFULLY PICKED HIS PATH TO THE TOP —

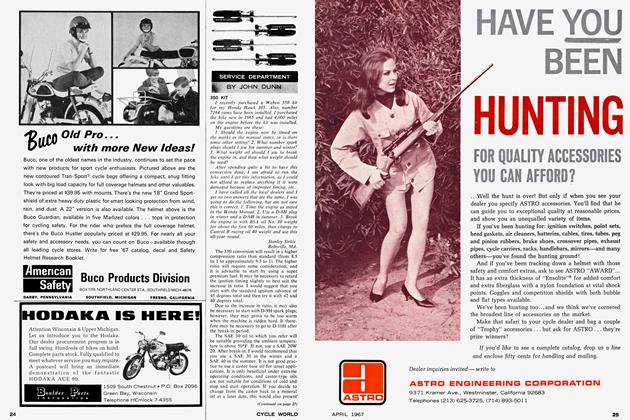

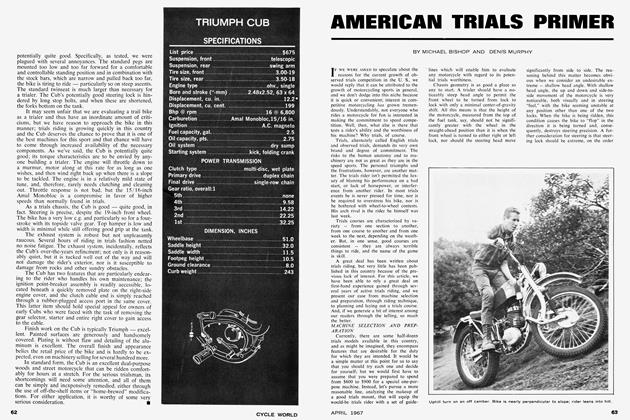

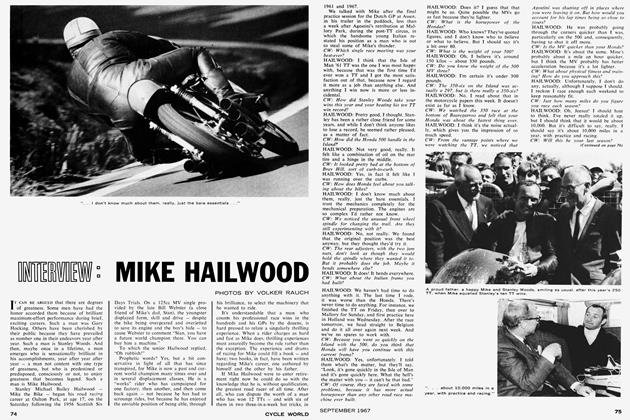

RECENT ENTHUSIASTS to the sport of motorcycling will know the name of Sammy Miller only as the top trials rider in that rather specialized branch of the sport which flourishes in the British Isles, but which is gaining in popularity both in Europe and the United States. What is not so well known is that Miller has tried most branches of the sport and met with success every time. He first came into the public eye in 1953, when he won both the 250cc sand racing and scrambles championships of Ireland, completing the same double the following year, when he also entered and won his first road race, the Cookstown 100, on his AJS. The following two years saw Miller winning most of the Irish road races, and in 1956, he led the 250cc TT until engine trouble sidelined him. He rode works Mondials in 1957, finishing third in the 125 and 250 world championships behind Tarquinio Provini and Cecil Sandford. In 1958, he rode works Ducati and CZ machines in the TT, but retired from road racing at the end of that season.

Sammy dabbled in scrambling up to 1961, winning many Centre events, but, while riding a works James, was “steam rollered” by a Gold Star in an unlimited race and sustained a broken pelvis, shoulder and ribs. Miller had joined the Ariel works trials team in 1956 and by 1962 he decided that since the sport was getting so specialized, he would do well to concentrate on it. His reasoning has proven more than true; trials riding is the one branch where a rider can practice as much as he likes, and build his own bike with a genuine chance of winning. Sammy did just that with his 497cc Ariel single and has been British Champion for the last eight years. It looks like he's planning to hold the title for the next eight.

Sammy has won the Scottish Six Days three times, the British Experts four, and won every national in the calendar at some time or other. His total of national wins is unknown. To that must be added six gold medals in the ISDT and the rare distinction of having ridden for the Vase team of two countries, Ireland and Great Britain, having been a trophy team man for the past three years. He has also won many international trials in Europe, including such famous events as the Polish Tatra trial, and Belgian Lamborelle and the French St. Cucufa.

Who better, then, to tell us about trials riding?

CW: How long have you been riding trials, and how did you become interested — that is, did you have other trialsmen in the family, or did you discover the sport by yourself?

MILLER: I started riding in 1953 on my SHS Special, which was a 197cc Villiers engine in a suitably butchered Matchless frame from the middle 1930s. There was no enthusiasm in the family for motorcycles. My father, who was a builder and decorator, frowned on my early escapades, and neither my brother, who entered the church, nor my sister showed any interest. But when we were kids, Benny Crawford, Tommy Robb and I used to rush around on push bikes, invariably ending up at Artie Bell’s place to look at his bikes.

CW: We know that there is probably no single factor, such as conditioning, practice, native ability or commitment, that would net a trialsman the degree of success you’ve enjoyed, but is there one factor that you feel is more important than all others?

MILLER: This is a question that I am often asked. Artie Bell, who, as you know, rode works Nortons, answered “enthusiasm” when I asked him, and though I did not think much of the answer at the time, the more I think about it, the more true I find it to be.

CW : What kind of meeting—categorically —do you prefer? What type of section do you find the most interesting and challenging to ride?

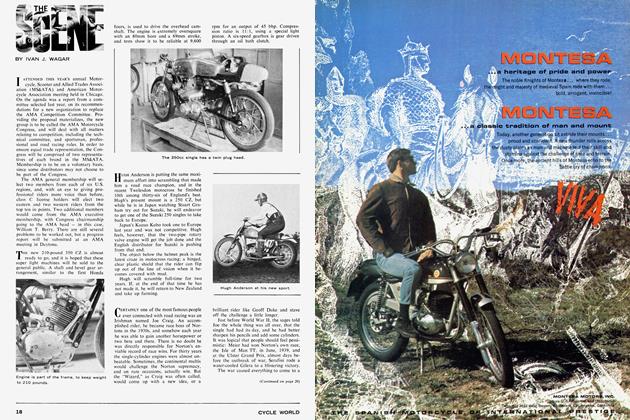

MILLER: Oh, without doubt, the Scotttype trial, where one is up against the clock as well as the sections. Having to keep to a time schedule sorts the men from the boys and forces a rider to get on with the job of riding the sections and not hanging around waiting to see how everyone else does it first. And the more difficult the sections, the better, the best being almost impossible natural ones, where no tape is needed to define the limits; like the Loch Eild path in the Scottish Six Days, which although not all that difficult, consists of 15 sections in threequarters of a mile.

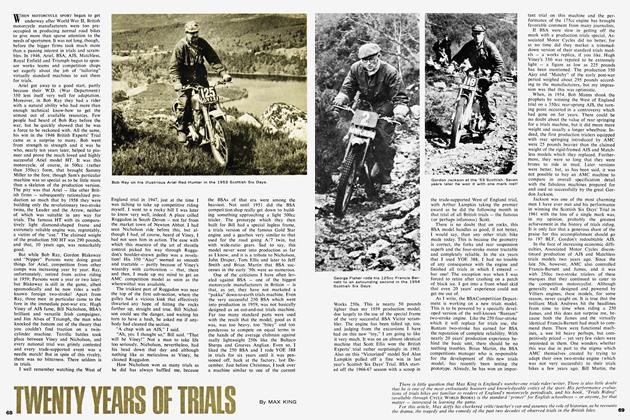

CW : How do you view the phasing out of the 350 and 500 thumpers and the phasing in of the lightweight two-strokes? Despite your very practical choice of your current machine and your apparent openmindedness about equipment, do you feel nostalgic about the diminishing number of four-cycles in trials, especially in view of the work you put into your Ariel?

MILLER: Well, we have to march with the times, and the British manufacturers have only themselves to blame, as the bigger bangers would weigh around 310 pounds when last made. My own Ariel, which you mention, was down to the 245 mark when I sold it a couple of years ago. I got more satisfaction riding that than a two-stroke, but it seems the impossible would have to happen before the big bikes returned. Anyway, the power to weight ratio of the Bultaco Sherpa is far more competitive, even compared with my old Ariel.

CW: What factors go to make up a really good trials bike?

MILLER: Without doubt, the primary factor is frame design, for good handling is essential. Then, one needs plenty of torque and correct gearing. This does not mean that I change gearing from one event to another; neither would I recommend it, as the essential is to know the capabilities of one’s machine, so that experience then tells the rider the right gear at the right time.

CW: We understand that the Bultaco Sherpa T — whimsically referred to as the “Sammy Miller autograph model” — is considerably more than a line model you found to your liking, and is, instead, a model developed by you with the cooperation of Bultaco. Just how much of the bike’s design are you responsible for?

MILLER: Virtually all of it. Señor Bulto spoke to me at the 1964 ISDT in Czechoslovakia, saying that he wanted to produce a trials bike and would give me a free hand in building the model. I went to Barcelona the following month and designed and built the frame. I took my Ariel for comparison, and with four mechanics, did all the testing on Señor Bulto’s farm. At the end of two weeks, the Bultaco was better than the Ariel. I had insisted on a capacity of 250cc, but at that time there was no Bultaco engine of that size. Gear ratios, torque and 20 bhp were additional requirements, as well as plenty of flywheels, and the engine has, by design, virtually got five.

CW: Isn’t it a bit unusual for a factory to entrust so much of the design of a production model to a rider?

MILLER: Yes, that is no doubt true. But you don’t get a steam hammer to swat a fly. Bultaco are a go-ahead concern who believe in the right man for the job. My bike is and always will be a mobile test bed, incorporating improvements year by year in the production model. An example of this is a special low third gear of 17.5 to 1 I tested, and is now standard on 1967 models. Señor Bulto knew what he was after and signed me on a two-year contract to achieve it. The contract expired last December and has now been renewed for three years. Now, inside three years, a thousand of those bikes have been sold — almost half in England — which is surely a pretty good vindication of his action.

CW: Would you mind revealing some of your secrets — for instance, how would you deal with a rock-filled stream?

MILLER: Let me say straight away that each section must be treated on its merits, and on a multi-lap event it should not be assumed to be the same as before. Never use the clutch except on ridiculously tight turns, and always inspect each section to find the right path — the smoothest, but walk through first to find out if the rocks are likely to move and throw the bike off line.

CW: A slimy off-camber?

MILLER: Bags of body lean and delicate throttle control.

CW: A steep ascent on loose shale?

MILLER: Maximum speed in second or third according to approach.

CW: A steep descent into deep mud?

MILLER: Clutch home, picking best line for second gear blast through the mud.

CW: A dry, deep-sand trough?

MILLER: Take it in second as fast as possible.

CW: Rock gardens?

MILLER: Same as for the stream; take the smoothest and flattest line.

CW: Surfaces covered with wet leaf mulch?

MILLER: Hit all cambers as straight as possible.

CW: We’re back-tracking a bit here, with reference to a proper trialer, but what guidelines would you put down in regard to man/machine relationship — bar type and position, foot pegs, seat, controls and the like?

MILLER: Perhaps I’m biased, but the Sherpa is the nearest to a perfect standard production model for the ideal riding position. But, every bike must be adapted by the rider to suit his own taste so “personalize” it.

CW: Do you feel that it’s possible for a novice to get an accurate picture of trials, and for that matter, his own potential in the game, with what we call a “play scooter,” that is, a trail bike or a sport model that has been set up to do a passable job of off-the-road riding, or do you feel that only a really proper trialer would tell the entire story?

MILLER: In Europe we do not have trail bikes, but from what I have seen of them in magazines, they appear to be ideal to start on, and there seems to be no reason why one should not be entered in a trial. If clubs do not already do it, I suggest that they have a separate class in events for trail bikes as an experiment.

CW: Is a trialer necessarily a one-purpose mount — arranged solely for the slow and skillful go — or can it double as a play bike and still be a good trialer?

MILLER: This is linked in a way with the last question. As a general rule let’s say that a trailer would not necessarily make a good trials bike, but a trials bike would be an exceptionally good trailer. Don’t run away with the idea that a trials bike is arranged “solely for the slow and skillful go.” A rider really has to get cracking in a trial like the Scott to average over 20 mph.

CW: Would you recommend a good, allround riding kit — one suitable for cold wet climate, as well as generally warmer weather with occasional nasty days in mind?

MILLER: Well, Belstaff have produced an excellent lightweight trials suit and will shortly be selling the Sammy Miller riding boot. Need I say more?

CW: Who do you think are the two best trials prospects in England at the moment?

MILLER: Without doubt, Mick Andrews and Alan Lampkin.

CW: Do you think trials schools help a rider?

MILLER: Well, the Royal Air Force have asked me to run a three-day course for the past three years so I think that speaks for itself. The first two days are spent on instruction, and the third day as a trial. I have also run courses in Belgium and Germany, which was attended by Gustav Franke, without doubt, the best of the European riders. Class size is usually between 30 and 40. If someone would like to pay the expenses, I’ll run a school in California and use a Sherpa straight from the stock of the local agent. Then you and the pupils can judge for yourself.

CW: If there is no British Trophy or Vase team, will you ride in the ISDT this year?

MILLER: No. As it is run at the moment, it is a waste of time rushing around for six days to win a gold medal along with dozens of other riders. The 1965 event was a classic, and winning a gold then meant something. But now, the only thing to achieve is top of the bonus points.

CW: If you were approached for advice by a novice to trials — someone with his first or second bike who had sufficient hours of off-the-road riding to understand the fundamentals of riding on cobby ground — what would you offer as ground rules for playing the trials game?

MILLER: Keep fit. Personally, I neither smoke nor drink, though trials organizers have nearly driven me to drink, as I have won over 30 beer tankards. Concentration and practice1 with tip-top machine preparation. Ride as much as possible over as big a variety of terrain as possible. In England, it is possible to ride every Sunday except Armistice Sunday, and during the winter, two rides a week are possible. Dedication is the best word.