C. R. AXTELL, MASTER TUNER

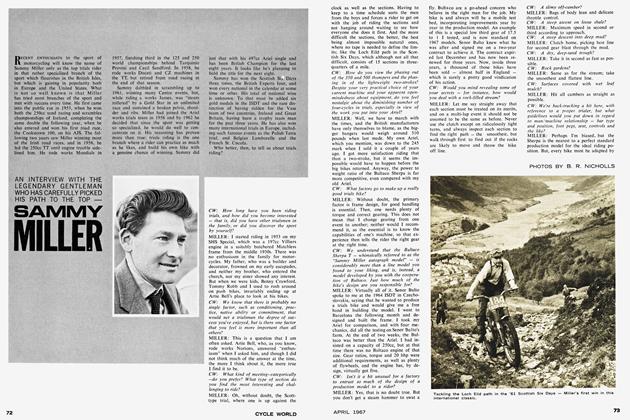

An Interview With One of America’s Leading Exponents of Flow Theory, Who, Among His Other Talents, Makes Sammy Run.

IF THERE IS ONE CATEGORY of individuals that the sporting press is interested in, it is winners. Granted, there is frequently a great deal of the human drama surrounding the also-rans, but these attendant tales invariably lack the punch — the hammer — that accompanies the stories of those who are outstanding in their respective fields. The punch, of course, is a product of their accomplishments, but we feel that the more significant side of the story is the technological advancement of the motorcycle sport for which these “doers” are responsible.

Some months ago, a germ of an idea emerged from the collective heads of the CYCLE WORLD editorial staff — an idea for a series of interview articles involving the people who are making the spoked wheels turn in this country and elsewhere. Last month we presented, without fanfare or ballyhoo, the first piece in this series — the Ekins Metisse project. We excuse our lack of trumpeted introduction by saying that we were unsure of the reception to this approach. Happily, the new game was well received; happily, because we are excited about pursuing the project; and happily, because our readers find it worthwhile and refreshing. So it is that we launch into number two of our motorcycle design series. First, however, we would offer a word of caution: Many of the points advanced in this series will be unsettling. They will up-end a great deal of “common knowledge.” This is not an unfortunate by-product of the project, but rather one of its principal goals. Also, it’s doubtful that you will find panaceas and hard and fast go-to-it answers, for this is not the intent. Instead, we must adopt an openheaded stand like that of Socrates who, when asked by the sophists what he had given the young men of Athens for truths after he had purged their heads of the widely held misconceptions of the time, replied, “Hercules was only required to clean the Aegean stables, not replenish them.”

It is more than fitting that the subject of this month’s interview, C. R. Axtell, is a bit of a machine-age Socrates. Axtell is not an answer man, but a question man. He belongs to that rare fraternity that insists upon practical truth and relies on theory only insofar as it provides a reasonable springboard.

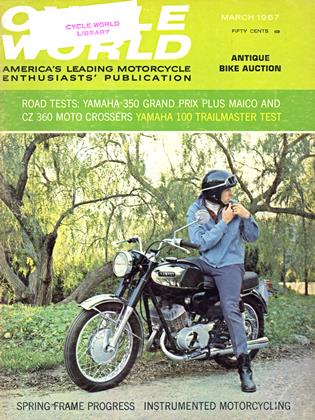

Axtell’s shop in Glendale, California, contains all of the necessary equipment — lathes, drill press, mill, grinders, and whatever — to qualify it as a builder’s emporium. But then, there is the room, situated between his two modest machine shops, where C. R. spends most of his time. The room houses two devices that are very dear to C. R.; a Zöllner dynamometer and an Axtell flow bench. This is the room where the secrets are disclosed, but only to C. R. and the paying customer. Axtell’s regard for security and confidence would make J. Edgar blush.

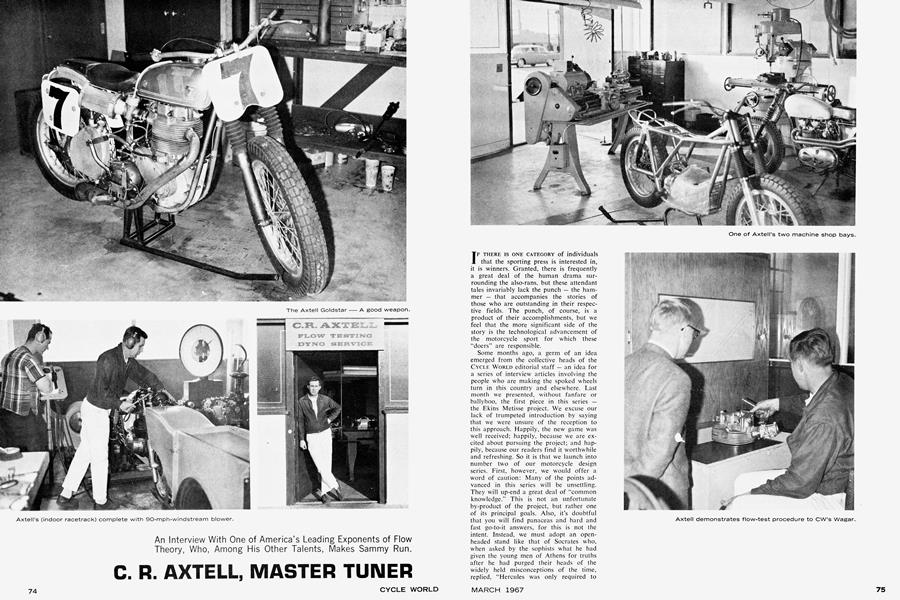

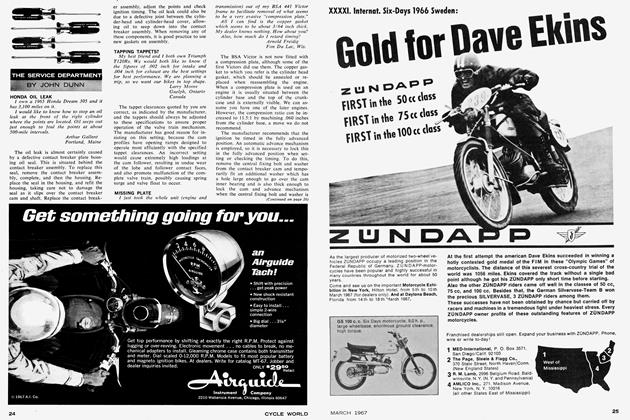

For credentials, Axtell points confidently to his activities in hot-rodding during the period preceding blowers and nitro. As the sport grew up and machinery became more expensive, C. R. lost interest and began casting about for a new unspoiled area, finding it very shortly in the then-budding field of motorcycling. That he and motorcycles have been good for each other is particularly evident when looking at the Ascot V^-mile ledger for the past four years: in four full seasons of racing-some 130 main events — Axtell’s Goldstar-based flat tracker, ridden by Sammy Tanner, has seen only a handful of retirements caused by mechanical failure. But, this is only a small part of the story. In the past four seasons, Tanner has ridden the Axtell Goldstar to numerous first places in heat races, trophy dashes and main events at Ascot Park, in addition to his wins at Heidelberg, Springfield and heat races at Sacramento, where the bike holds the lap record.

On the day we chose to interview Axtell, there was a dyno project underway. But that would have been the case for just about any day, because his dyno, which receives its input from a test motorcycle’s rear wheel sprocket, is one of the most popular pieces of proving equipment in the country. Because of the testing activity our interview was frequently interrupted by matters that required Axtell’s presence, and thus the conversation will lack continuity. However, the essentials are intact — the philosophy, motivation and inspiration of one of the most knowledgeable tuners and sharpest wits in the world of motorcycling. CW: Where shall we start discussing tuning — with parameters like compression ratio, volumetric efficiency, and like that? AXTELL: We can start and end with those two points, if you like. They’re two terms that simply turn me off. First of all, “compression ratio” is meaningless. If we’re talking about a ratio of 10:1, say, all we really know for sure is that the volume of the cylinder with the piston at tdc is 1/10 of what it is with the piston at bdc. But, now what happens when we introduce the factor of late intake valve closing? It’s hard for me to believe that we can compress a full charge when the intake valve is open two-thirds of the way up on the compression stroke. You tell me, then, what’s the significance of the present method of measuring compression ratio. It’s not a constant, it’s a variable that is altered by changes in valve timing and the ability of a port to breathe, even though the cylinder and stroke dimensions remain constant. I believe that in the near future people will be measuring compression ratio from the time the intake valve closes to top center.

And now, that other slick term — volumetric efficiency. 7'hat one really escapes me. Anyone who can talk knowledgeably about volumetric efficiency is a lot sharper than I am — or they’re kidding themselves. As far as I can determine, it’s impossible to measure; like, how do you measure the amount of fuel charge that exits through the exhaust port during overlap, even when you know how much is taken in through the carburetor on a given-size engine at a given rpm?

CW: What factors do you consider important in regard to performance? AXTELL: There are only two values that are honest and worth considering: torque and rpm. These are a builder’s products, the things the rider gets when he turns the “loud handle” on. Ideally, I tune for as broad a power band as I can possibly get. Graphically, a good torque curve will rise gradually and maintain a flat peak output level. An example of a really good torque curve is the one produced by a Triumph twin. They’re beautiful. I love ’em. They come up quick, hang on over most of the range, and then drop ever-so-slightly close to peak revs. This is probably the major reason why Triumphs are so successful in TT and desert racing. 7'hat good usable power is always there. When you need more power, you dial it in. You need a little more, you dial it in. The power is predictable — not explosive.

CW: How would you relate the power curve of an engine with its peak horsepower output on the basis of importance? AXTELL: I’d say that that would depend to some degree on application. But, if we’re talking about dirt-track engines, I’d have to go along with a fast buildup of power. The half-mile is similar to drag racing in one respect: the object of the game is to have a low elapsed time from one end of the straight to the other, and this does not mean getting down to the end of the straight 20 mph faster but a halfsecond late. It means getting there first with a comparatively low top speed — in other words, accelerating like hell all of the way, not just at the end.

CW: Then, the high specific horsepower can be a disadvantage?

AXTELL: No. Horsepower is never a disadvantage. But, without a workable power band it is certainly not advantageous.

CW : Do you feel that the power characteristics of a single are more desirable than those of a twin for dirt-track racing? AXTELL: No, not actually. There’s certainly ample evidence that the twins can do the job. Harley, Triumph and BSA have all done an equally good job of dirt-track racing. And, you know why they’re so successful? They put more time, energy and money into racing in this country than anyone else! And they’ve done more to advance racing in this country than anyone else. People like Dick O’Brien (H-D racing chief) and his boys are really serious about their work, and that’s why they’re so successful. I love ’em. They’ve really been good for the sport.

CW: Now that we’ve entered into o discussion of racing in this country, tell us what you feel about the AMA.

AXTELL: I love the AMA with reservations. AMA rules give everybody a chance. You don’t have to have thousands of dollars tied up in an exotic racer to be competitive in this country. Their rules encourage careful, patient refinement of reasonably priced production machinery and I feel that this is how it should be. The only rules that are restrictive are three number plates, two wheels and one rider. Aside from these, you have quite a bit of latitude.

CW : Do you do a lot of work with nonprofessional individual builders?

AXTELL: Yes, quite a bit. Some of this work is pretty entertaining, too. Occasionally, someone will come in with their supermodified bike with all of the good hardware attached and all of the proper things done. I put the bike on the dyno and we discover that it isn’t putting out what the manufacturer specifies for the stock version, so we start replacing the go-fast parts with the original ones, until we bring the power back up to where it was in the first place. The customer will go away thinking that maybe the people who design production bikes for a living aren’t so stupid, after all.

My favorite dyno customers are those who are sincerely interested in increasing the performance of their machinery through step-by-step refinement. When they’re finished with their equipment, they have something that doesn’t differ radically from the stock article, but puts out substantially more power over a broader band.

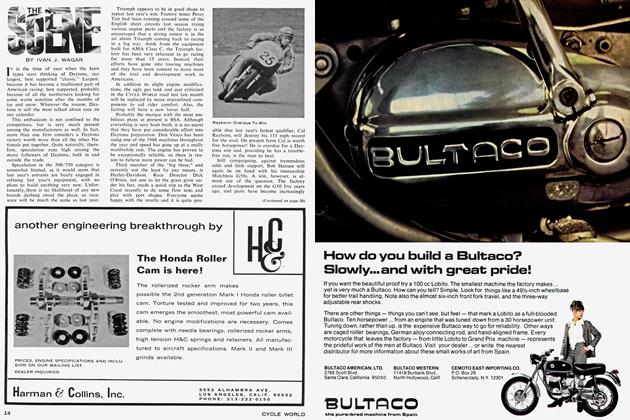

CW: It’s apparent that you rely pretty heavily on your dyno and flow bench for your tuning. Is the information gained with these always predictable, or do you still rely on race proof of your ideas? AXTELL: I place a lot of trust in these two pieces of equipment. They tell me just about everything I want to know. When I truck the Goldstar to Ascot on a Friday night, I know what it’s going to do. I don’t go there to tune. I go there to race. I know pretty well where it’s going to finish, provided Sammy doesn’t do something silly, and he hasn’t so far.

(Continued on page 81)

The more important piece of the two is the flow bench. If I were limited to only one device I’m afraid that the dyno would have to go, because all it does, really, is replace the race track. If I had a nice little track right outside the shop, I could get by without the dyno; but I don’t know of anything that would replace the flow bench. It takes the guesswork out of port design and this is the heart of tuning.

CW: What, exactly, do you learn from the flow bench?

AXTELL: First, the flow bench helps me to analyze the potential of a port. I learn what it is capable of doing. I can relate an intake port to an exhaust port and discover whether or not they are compatible. The relationship of the two is very important. The balance of intake and exhaust flow capability is critical and precise, but the importance can be illustrated by comparing a manhole cover for an intake valve to a roofing nail for an exhaust valve.

CW: What factor determines whether or not a port is as good as it should be, and how do you correct it?

AXTELL: A port is correct when it is capable of meeting the demands of the engine at maximum piston velocity. If a port is incapable of handling the flow requirements, it has to be beefed up. By that I mean it is enlarged or contoured, so that its capability meets the engine’s requirements. It’s in this area of tuning that the flow bench is invaluable. Not only will the bench tell you whether the port is good or bad, but it will also tell you precisely w'here you have to add or remove metal. It takes all of the guesswork out of the game.

CW: Isn’t is possible to have a port or an entire tract too efficient and free from restriction? We know, for instance, of a popular 500cc production scrambler that is a bear to operate with the A mal GP carburetor that it comes with, but is completely manageable wih a smaller, less efficient carburetor. How do you account for this?

AXTELL: First of all, many people feel that the GP is temperamental. Nothing could be further from the truth. The truth of the matter is that the GP is probably about as good a carburetor as you could find. I think I know the bike you’re referring to. I’ve run flow tests on the head of this engine, and its breathing trouble sure isn’t at the intake side. You might sum it up by saying that this particular engine suffers more from constipation than it does from asthma.

CW: You’re regarded by many in the motorcycle racing game as one of the exhaust system players, and particularly so with regard to megaphone tuning. How do you feel about that?

AXTELL: That’s somewhat correct. On any Thursday afternoon during the Ascot season, after I’ve buttoned up the Goldstar for Friday night, I’m an authority on exhaust systems and megaphones. On Saturday morning I know absolutely nothing about exhaust tuning and really doubt my theories. By Monday I’m starting to question the bike, and by Tuesday I completely mistrust it. By Wednesday I’m really gaining ground, and on Thursday, again, I’m an authority.

CW: Judging by all of the experimental exhaust hardware you have on hand, it would seem that you place a great deal of importance in exhaust tuning.

AXTELL: Yes, I do, and it deserves a lot of attention and effort because it is important. A well-designed megaphone on a properly refined engine, will not only yield a significant horsepower increase, but it will considerably broaden the power band. Exhaust tuning will let you do just about anything you want to with the engine’s output. I, like many others, strongly feel that exhaust tuning is the last frontier in tuning. One rather interesting point that I would like to add here is that a good megaphone, a really proper one, will destroy itself — just tear itself to pieces when it is doing its job, really doing it.

CW: Do you find exhaust tuning to be any more critical for two-strokes than fourstrokes?

AXTELL: No, not all all. I don’t find that twoand four-strokes differ much at all in their problems. They respond similarly to the same solutions. The only difference I’ve discovered is that one has its overlap at the top and the other at the bottom.

CW: Are you currently contemplating any projects involving exotic machinery? AXTELL: If you mean exotic like one-ofa-kind works stuff, the answer is no. They’re sort of interesting, all right, but I prefer to work with production pieces — the sort of thing that anyone can buy. Refining this type of equipment is much more interesting to me than playing around with something that no one else has or can get. There’s so much to be done with the stuff you can just go out and buy, that there isn’t time for the exotic iron.

CW: What are your feelings about the future? Do you have any long-range plans? AXTELL: I plan to go on doing just what I’m doing now — evaluating and refining the machines that are available to me. I could hold my own in the “down town” thing, all right. I’ve got a tight Ivy-League suit and a slip-stick for the breast pocket, and I can whip that little beauty back and forth with the best of them, dropping all of the proper terms and talking the talk, saying, “no, I don’t think that’s right,” even when I don’t know what is right. But that’s not what I’m after. I’ve got a lot of questions, more questions than answers. In fact, I don’t have many answers at all, and that’s what I love about my work.

There’s so much to learn. I really feel sorry for all of those people who already have all the answers. They wake up in the morning and don’t have any great experiments to conduct. I really feel sorry for them. ■