BAVARIA, NEW JERSEY

The Nettesheim plays host to the legendary motorcycles of Germany.

December 1 2021 KEVIN CAMERONThe Nettesheim plays host to the legendary motorcycles of Germany.

December 1 2021 KEVIN CAMERONBAVARIA, NEW JERSEY

The COLLECTOR

The Nettesheim plays host to the legendary motorcycles of Germany.

KEVIN CAMERON

I initially had no idea that anything like the Nettesheim BMW Museum existed in the United States. Peter Nettesheim, driven by enthusiasm for BMW motorcycles and by a powerful engagement with history, has accumulated and restored roughly 100 classic machines from that marque, including the oldest known BMW, an R32 from one of two original batches produced in November of 1923.

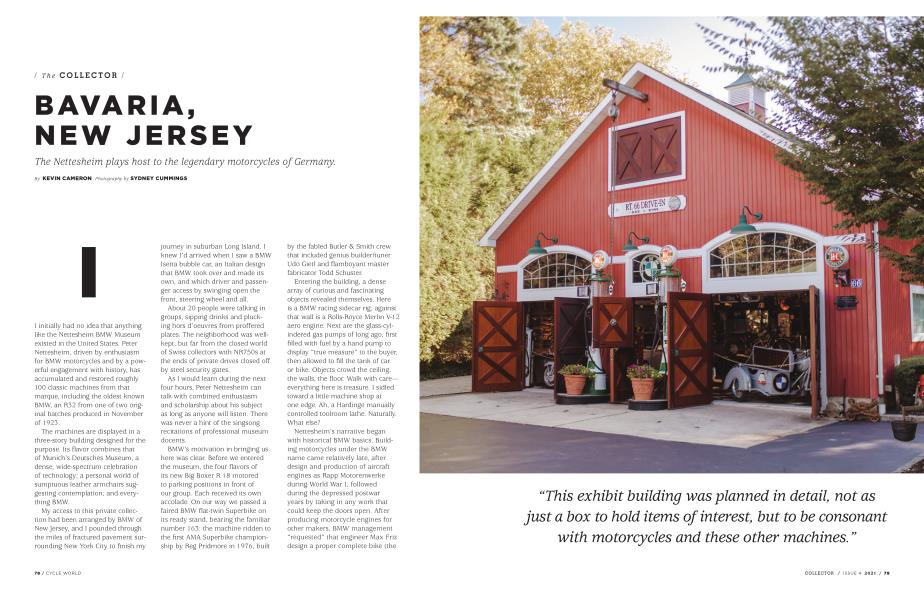

The machines are displayed in a three-story building designed for the purpose. Its flavor combines that of Munich’s Deutsches Museum, a dense, wide-spectrum celebration of technology; a personal world of sumptuous leather armchairs suggesting contemplation; and everything BMW.

My access to this private collection had been arranged by BMW of New Jersey, and I pounded through the miles of fractured pavement surrounding New York City to finish my

journey in suburban Long Island. I knew I’d arrived when I saw a BMW Isetta bubble car, an Italian design that BMW took over and made its own, and which driver and passenger access by swinging open the front, steering wheel and all.

About 20 people were talking in groups, sipping drinks and plucking hors d’oeuvres from proffered plates. The neighborhood was wellkept, but far from the closed world of Swiss collectors with NR750s at the ends of private drives closed off by steel security gates.

As I would learn during the next four hours, Peter Nettesheim can talk with combined enthusiasm and scholarship about his subject as long as anyone will listen. There was never a hint of the singsong recitations of professional museum docents.

BMW’s motivation in bringing us here was clear. Before we entered the museum, the four flavors of its new Big Boxer R 18 motored to parking positions in front of our group. Each received its own accolade. On our way we passed a faired BMW flat-twin Superbike on its ready stand, bearing the familiar number 163: the machine ridden to the first AMA Superbike championship by Reg Pridmore in 1 976, built

by the fabled Butler &. Smith crew that included genius builder/tuner Udo Gietl and flamboyant master fabricator Todd Schuster.

Entering the building, a dense array of curious and fascinating objects revealed themselves. Here is a BMW racing sidecar rig; against that wall is a Rolls-Royce Merlin V-l 2 aero engine. Next are the glass-cylindered gas pumps of long ago, first filled with fuel by a hand pump to display “true measure” to the buyer, then allowed to fill the tank of car or bike. Objects crowd the ceiling, the walls, the floor. Walk with care— everything here is treasure. I sidled toward a little machine shop at one edge. Ah, a Hardinge manually controlled toolroom lathe. Naturally. What else?

Nettesheim’s narrative began with historical BMW basics. Building motorcycles under the BMW name came relatively late, after design and production of aircraft engines as Rapp Motorenwerke during World War I, followed during the depressed postwar years by taking in any work that could keep the doors open. After producing motorcycle engines for other makers, BMW management “requested” that engineer Max Friz design a proper complete bike (the first BMW auto would not appear until 1927). As can happen when an engineer from one discipline (aircraft engines, in Friz’s case) designs for another, the result was a completely fresh look. The wood-and-fabric aircraft of the First World War would have been shaken to bits by the vibration of existing single-cylinder bike engines, so Friz chose the self-balancing architecture of a flat opposed twin, long called a “boxer,” with two crankpins at 180 degrees. He eliminated the problems resulting from traditional chain drives by unit construction, meaning engine and gearbox share a single assembly, and using Cardan shaft drive to send power to the rear wheel. Friz was critically aware of the need of engine cooling, as aircraft piston engines seldom operate at less than 50 percent power. Thus, he mounted his engine with its cylinders projecting left and right into clear air, its flow unobstructed by any other parts.

“This exhibit building was planned in detail, not as just a box to hold items of interest, but to be consonant with motorcycles and these other machines. ”

These were the virtues of BMW’s original R32 of 1 923, and of all subsequent flat-twin BMWs. Friz thereafter returned to his central interest—aircraft engine design.

Now followed anecdotes and explanations that would continue through a catered tent lunch and not cease until the end of our visit. When one of us exclaimed at the attractive finish on a strange bed-forward BMW in-factory transporter truck, Nettesheim noted that painting skills are widely available— just in this immediate community, he said, there are six painters who do quite good work.

But harder-to-fmd skills are needed to make sense of machines that time has altered through loss of parts or deterioration. For emphasis, he started its engine.

As I turned to a battered-looking BMW R75 military sidecar rig, I realized that smoke was drifting past it. The bike stood on what had been the cross-ties of a rail line, the rails pried up and missing. This was a detailed diorama of the end of the European war in 1945—so detailed, it included smoke.

Nettesheim told a story on himself. Having completed the mechanical restoration of one of the prewar twins, he was disappointed to see oil leaking from the felt seal around its gearbox output shaft.

“I went back and made sure of concentricity,” he said. “I checked again to be sure the felt was under the proper pressure. Still, the leakage continued. I didn’t know what more I could do.”

Then, on one of his European foraging expeditions, he put his problem to an experienced and knowledgeable older authority.

“You idiot,” his informant said. “Of course it leaks! Those gearboxes were never intended to be lubricated with oil. They were packed with grease!”

Up on a high shelf is a complex machine made entirely of brass. Nettesheim explained that this was a model of Nikolaus Otto’s first internal combustion engine. Scanning the room more systematically now,

I began to see all kinds of fascinating goodies tucked here and therefor example, raw unmachined castings for early BMW engines.

How have so many sought-after classics come here? The answer came in the form of another story. Nettesheim learned that a certain person had an R32 to sell in parts. He phoned, saying he’d come to look but that he had to know the asking price range. Arriving and liking what he saw, he was quoted the high limit. As he prepared to return to the airport, the seller said, “Perhaps you would care to consider the rest of the parts?” This was a BMW fancier who placed greatest value on the finished object. But to Nettesheim every part was familiar, and in an adjacent room he recognized enough parts to build at least one more R32. The deal was done.

Supported from the ceiling on four chains was a substantial BMW marine engine from the 1920s, an overhead-cam four-cylinder M4A12, its cylinders cast in blocks of two.

Its story made clear the strong trust between Nettesheim in the US and BMW in Germany. BMW had four such engines, one of which was on display. Would Herr Nettesheim care to display one of the three held in storage? Terms were for the lifetime of the recipient. In the past, Nettesheim had lent BMW the oldest R32 for display at the EICMA show, and perhaps elsewhere.

This exhibit building was planned in detail, not as just a box to hold items of interest, but to be consonant with motorcycles and these other machines. The floors above are supported by welded steel columns in truss form. A vehicle elevator able to lift cars cantilevers from one wall. The metal stairways suggest a steamship’s machinery spaces.

We were not shown the restoration area, although we did get a look at some as-found elderly BMWs which start and run. Nettesheim never once uttered the word “kompressor,” yet BMW record-attempt and racing bikes of the 1930s achieved great things with the same technology, which was then expanding the performance of aircraft— supercharging. Something to look forward to on another visit?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

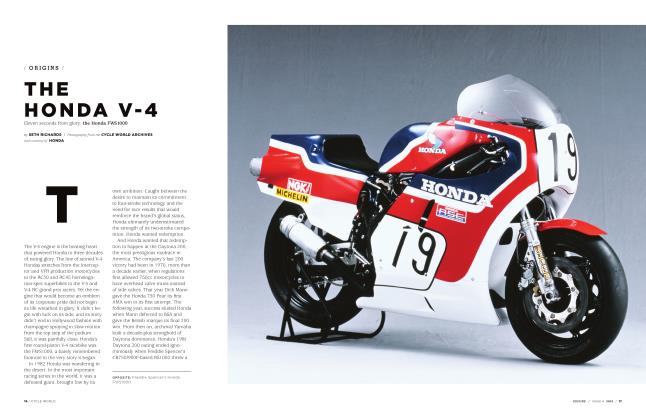

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTHE HONDA V-4

Issue 4 2021 -

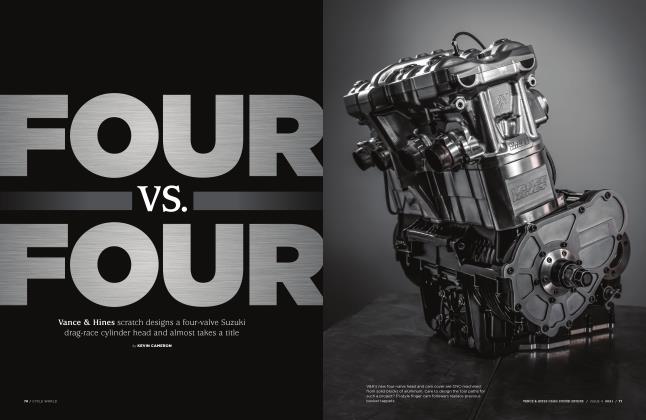

FOUR VS. FOUR

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

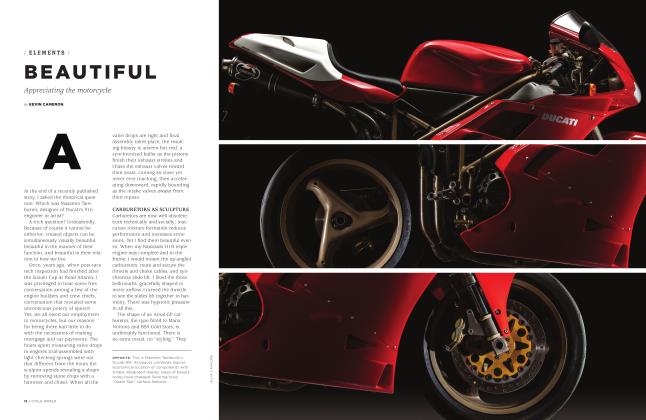

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSBEAUTIFUL

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

TDC

TDCHANDLING STRESS BY MOVING IT

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

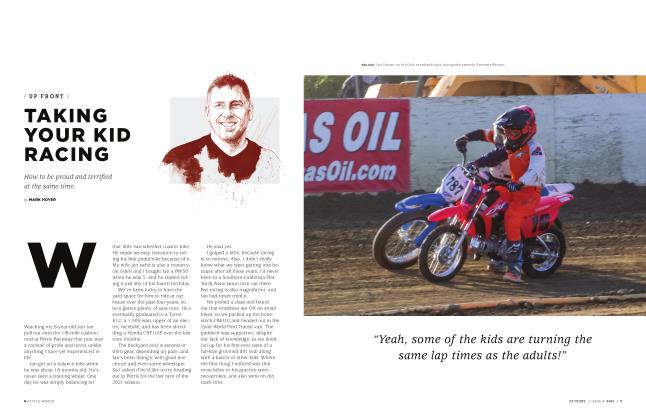

UP FRONT

UP FRONTTAKING YOUR KID RACING

Issue 4 2021 By MARK HOYER -

2022 APRILIA TUAREG 660

Issue 4 2021 By Justin Dawes