AGO

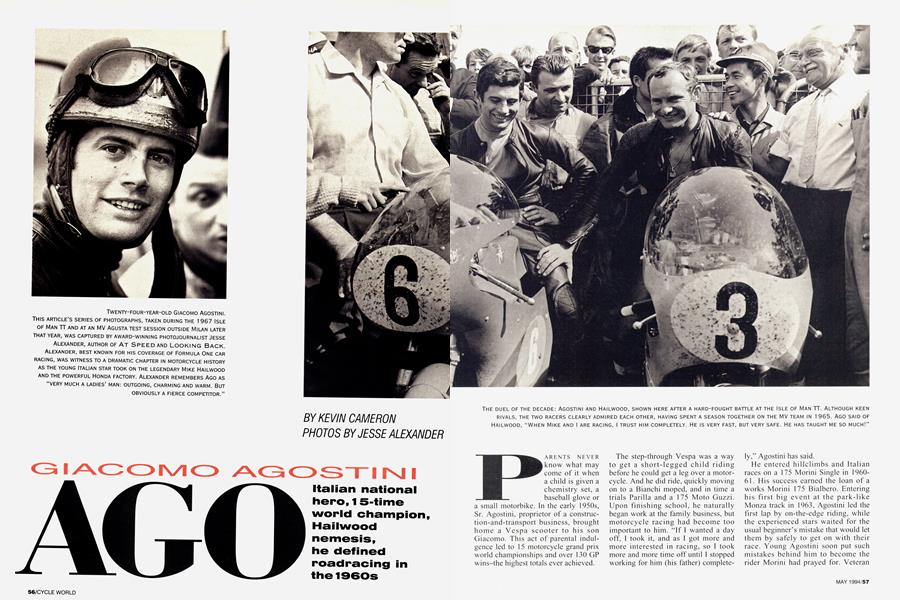

GIACOMO AGOSTINI

Italian national hero, 15-time world champion, Hailwood nemesis, he defined roadracing in the l960s

KEVIN CAMERON

PARENTS NEVER know what may come of it when a child is given a chemistry set, a baseball glove or a small motorbike. In the early 1950s, Sr. Agostini, proprietor of a construction-and-transport business, brought home a Vespa scooter to his son Giacomo. This act of parental indulgence led to 15 motorcycle grand prix world championships and over 130 GP wins-the highest totals ever achieved.

The step-through Vespa was a way to get a short-legged child riding before he could get a leg over a motorcycle. And he did ride, quickly moving on to a Bianchi moped, and in time a trials Parilia and a 175 Moto Guzzi. Upon finishing school, he naturally began work at the family business, but motorcycle racing had become too important to him. “If 1 wanted a day off, I took it, and as 1 got more and more interested in racing, so I took more and more time off until I stopped working for him (his father) completely,” Agostini has said.

He entered hillclimbs and Italian races on a 175 Morini Single in 196061. His success earned the loan of a works Morini 175 Bialbero. Entering his first big event at the park-like Monza track in 1963, Agostini led the first lap by on-the-edge riding, while the experienced stars waited for the usual beginner’s mistake that would let them by safely to get on with their race. Young Agostini soon put such mistakes behind him to become the rider Morini had prayed for. Veteran Tarquinio Provini on the Morini 250 had nearly taken the championship from Honda in 1963. Morini signed Agostini for the 1964 season, and he did not disappoint them, taking the Italian 250 title from the great Provini, now on the Benelli Four.

Eraldo Ferracci, today the U.S.-based team manager who took Ducati and Doug Polen to two World Superbike titles, was then a Benelli factory rider. Asked about young Ago, he replied, “In those days, he was animal.”

The major Italian factories had agreed at the end of 1957 to quit racing, for the availability of low-priced cars like the Fiat 500/600 had killed bike sales. Unlike the others, MV Agusta didn’t depend on motorcycles for survival; its major business was helicopters. Count Domenico Agusta, a son of the aircraft company's original founder, was a motor sportsman able to indulge his taste grandly. To win 500 and 350cc world championships, Agusta had imported foreign riders-Les Graham, John Surtees, Gary Hocking, and most recently, Mike Hailwood. When Agostini flashed into prominence, Count Agusta reached out and seized him.

Agostini’s freshman year on a 500 was the ultimate racing education. For tutor, Mike Hailwood: for equipment, the multi-cylinder MVs. His world expanded from Italy to the grand racing venues of Europe and the world. Hailwood showed him the good line in practice, then switched places to critique Ago’s moves. It worked. Giacomo Agostini won his first GP that year, the 350 event at the German Nurburgring.

Learning was probably cult for to Agostini, ride not the diffiMVs who had mastered the narrow power of the Morini. To make power despite limited revs, Singles were tuned to use intake and exhaust resonances, effective only over a narrow speed band. By contrast, the MV Fours made power through high rpm, and could be tuned more mildly. Hailwood described their having a “delightfully smooth and seemingly endless flow of power.” Veteran tuner Nobby Clark points out that the MVs were, however, much less forgiving than the Singles. A Single could slide in control, but the MV-Fours would bite you.

Thus, Ago’s early career was unique. Instead of scratching his way to success against a horde of identically equipped rivals, he learned out front, on machines that usually provided comfortable superiority. Countless racing miles let Agostini perfect smoothness and economy of action. Professional flying has been characterized as “years of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror,” but grand prix racing in the 1960s, with its bad weather, oily surfaces and unprotected guardrails, provided moments in plenty.

There were other contrasts. 1960s GP racing existed on two planes. On top were stars like Agostini and Hailwood, traveling in luxury. Below were the privateers. Today’s GP paddock is filled with giant motor homes and transporters, but then it was a gypsy encampment. Privateers lived in small trailers, sharing space with machines and fuel. Wives and girlfriends washed and hung out clothes wTile riders schemed for meager starting money. Now, machines of top and bottom finishers are much the same, differing mainly in use of exotic materials and computers. In the 1960s, after the 5()0cc MV and Honda Fours howied past, the rest of the field droned by on Singles, 20 miles an hour down on top speed.

Despite this, Ago soon had his hands full. Hailwood was hired away by Honda after 1965 to ride the new Four. In the 500 class, Honda desperately lacked what MV had: experience. Hailwood’s Honda was not only unreliable, it was downright unstable. Agostini took the title from his mentor of the year before in alternating hardfought races and Honda DNFs. At the Dutch TT in particular, Hailwood prevailed by 5 seconds, but was so exhausted at the end that he had to be assisted to the podium. Ago repeated the following year. His weapon was the compact and handy three-cylinder MV 500 that the autocratic Count Agusta had ordered built over his engineers’ objections. Then Honda switched to auto racing.

The years rolled by and Ago and his MVs amassed world titles. In 1971, New Zealander Ginger Molloy livened things up by finishing second to Ago on a private Kawasaki two-stroke Hl-R-a portent of the future. Japanese development in the smaller classes was furious, as engines went from Twins to Fours, Fives and even Sixes. For MV, still secure at the top, no such effort had ever been necessary. Sound engineering combined with conservative preparation and Agostini’s fast, secure riding had always been enough.

At the end of 1972, Yamaha introduced its two-stroke, reed-valve OW20 GP Four. The brilliant Jarno Saarinen, who had challenged the 350 MV with Yamaha’s two-stroke 350 Twins in 1971, now brought factory two-stroke power to 500cc racing. For the moment, the MV remained the more powerful machine, but the motocross-stimulated suspension development undertaken by Yamaha made its bikes faster into and through turns, while the MV accelerated harder and had a top-speed margin.

Amore lenge from to Phil important Agostini Read, former chalcame Yamaha factory star. Read, a tough, experienced rider and an ambitious, highly competitive person, was hired by MV to team with Agostini. Too much was happening at once. Domcnieo Agusta, the force behind the team, had died in Milan in early 1971. Meanwhile, Gruppo Agusta had designed the A129 Mangusta anti-tank helicopter, and the Italian government wanted and took a 51 percent interest in the company. Without Agusta, the racing team shrank in importance. Just as intensive development was essential to counter the Japanese challenge, it became politically and financially impossible.

Phil Read knew factory racing politics. As the Yamaha improved, Ago became critical of the MVs, but Read understood the uses of action-and silence. After a professional lifetime with MV, Giacomo Agostini felt himself losing ground. Read, a hard man who had thrived on interpersonal rivalry, pushed on to become 500cc world champion in 1973 and ’74.

Was Agostini the protected, insulated figure his critics described, able to calmly win countless titles only by having the fastest machine? Or was he a real champion who rode only as fast as necessary to win, as his admirers believed? Now was the time of trial. Yamaha needed a championship-quality rider to replace Saarinen, who had been killed at Monza. The choice fell upon Agostini.

His first ride for Yamaha came at Daytona, on the completely new TZ750A. With his characteristic calm and apparent disregard for racing’s pressures, Agostini practiced competently but without distinction. In the race, he survived several challenges, often seemingly out of the results, but came through to win the 200-miler despite suffering terribly with the unusual heat.

In the GP season that followed. Ago rode well, but rapid machine development sometimes gets in the way of winning races. Read was champion, with his new MV teammate Franco Bonera second. Ago had to be content with the 350 title, won on the new liquid-cooled Yamaha Twin over MV’s new-technology, 17,000-rpm, 16-valve Four. The following year, Ago got what he wanted; Yamaha fielded a fast and reliable 50()cc two-stroke, and Agostini pushed Read down into second place.

For MV, machines 1976, running Ago under returned the great his own to Team Agostini banner. But time had run out. Without serious development, the MV Fours were now behind in all areas. The hoped-for new engines-a bulky Boxer Four and a new transversale engine with FZR-like inclined cylinders-had not materialized. The final blow was Ago’s test of a private Suzuki RG500 in mid-season; even it was clearly superior to the Italian machine. The future had ended for MV, which had failed not because the four-stroke principle had nothing more to give, but because the parent company had lost the means and will to continue the work.

Agostini formally retired the following year, but his name now had enormous value. Perhaps an entirely different career in film? Ago’s handsome features did grace more than one B movie, but this hardly comported with the dignified figure he had cut in racing. Ago tried-like Surtees and Hailwood before him—to enter car racing, but the intensity that had put Ago on the factory Morini in 1964 was no longer available to him. He found a new role as team manager with his old benefactors, Marlboro and Yamaha, after 1983.

Ago as manager did not please everyone. Eddie Lawson, among others, had differences with him. A new name, “Ago-stingy,” was coined. On the other hand, Kel Carruthers, who worked with Ago for 5 or 6 years, says the man was never other than correct in his dealings with him. He suggests that a contract is the proper basis for professional relationships, and that those who don’t write their own contracts (this often includes riders) may miss what is required of them. Still, there are too many “Ago stories” to be entirely ignored. They consistently describe a man whose eagerness for financial gain has hurt him, cutting him off from opportunity, antagonizing potential allies. Fact, or just the railings of the envious?

Agostini has advised riders, “In the years when you are riding, that is no time to think about money. Just put it in the bank and concentrate on your riding. When you retire, there will be plenty of time for investment and management.” Wise words. Better indeed, if possible, to put money out of mind and work on the crucial problem of how to go fast and finish races.

hile Team Agostini/Marlboro/ Yamaha operated out of Italy, the Kenny Roberts organization, as tightly focused on racing success as KR himself had been, came to full strength. The Roberts team eventually assumed the dominant role as the major Yamaha team in GP racing. Team Agostini/ Marlboro faded away. Today, Agostini manages Cagiva’s promising GP team, handling the business side while Kel Carruthers and Firenzo Fanali manage the engineering for riders Doug Chandler and John Kocinski.

What can we say in sum? Here is a man from a family in commerce, who rose by his own quality and by opportunities taken, to become an Italian national icon and a world sports figure. When success became easy, he enjoyed it. When a challenge was presented, as by the mighty Hailwood in 1966-67, and by the aggressive Phil Read in 1972-74, he was equal to the struggle. Yet, as we all do, he has limits. If critics suggest that money may mean too much to him, or that he always plays to the audience and the cameras like a film star, can we accept this possibility? We must, or we set the scene for our own disillusionment. We are fatally tempted to hold our heroes to impossible standards, and we shouldn’t. Anyone with direct knowledge of riders knows that the competitive, “me-first” personality that wins races, does not operate solely on the racetrack, and does not cease to exist when the helmet is zippered into its bag for the last time. It simply takes on new forms and continues its life. Giacomo Agostini, winner of more GP titles and races than any other rider before or since, is a man like other men, with a man’s contradictory and fascinating mixture of strengths and weaknesses, wisdom and foolishness.

That mixture has earned him his place in the history of motorcycling.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue