The Dunstall Chronicles

UP FRONT

David Edwards

BUYING A HOUSE IS A TERRIBLE THING. Not only does it take up every last drop of savings-account money-funds that rightfully should be used for the procurement of 1970 Indian Enfields and 1956 Gilera Bicilindrica 300s—it forces other, equally traumatic sacrifices.

In my case, first to be offered up was my 1991 Sportster 1200. It should bring enough to buy a decent refrigerator, a washer/dryer combo and some living room furniture. A dubious trade, I know, but a man needs to keep his skivvies clean, his Bass ales chilled and have a place to prop his feet while flipping between Letterman and Leno.

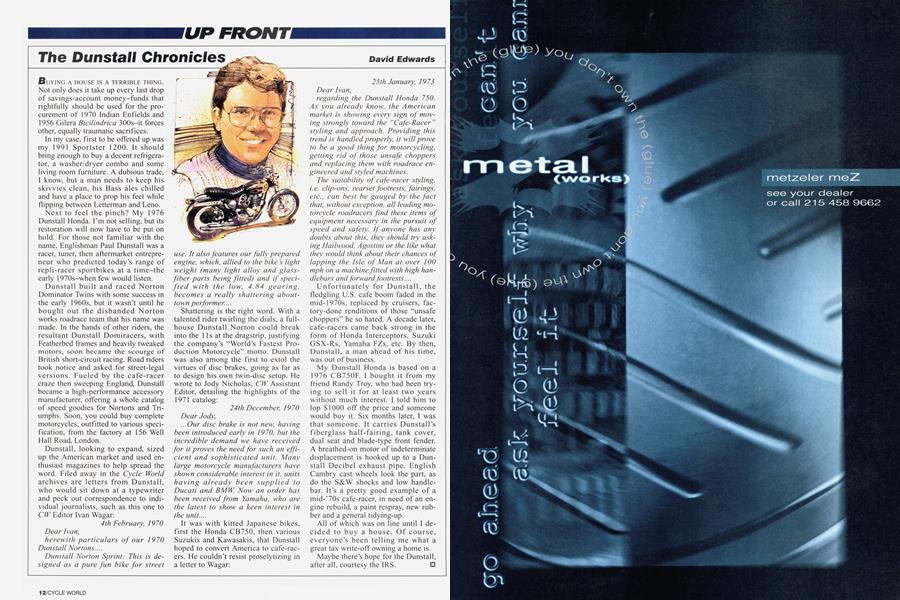

Next to feel the pinch? My 1976 Dunstall Honda. I’m not selling, but its restoration will now have to be put on hold. For those not familiar with the name, Englishman Paul Dunstall was a racer, tuner, then aftermarket entrepreneur who predicted today’s range of repli-racer sportbikes at a time-the early 1970s-when few would listen.

Dunstall built and raced Norton Dominator Twins with some success in the early 1960s, but it wasn’t until he bought out the disbanded Norton works roadrace team that his name was made. In the hands of other riders, the resultant Dunstall Domiracers, with Featherbed frames and heavily tweaked motors, soon became the scourge of British short-circuit racing. Road riders took notice and asked for street-legal versions. Fueled by the cafe-racer craze then sweeping England, Dunstall became a high-performance accessory manufacturer, offering a whole catalog of speed goodies for Nortons and Triumphs. Soon, you could buy complete motorcycles, outfitted to various specification, from the factory at 156 Well Hall Road, London.

Dunstall, looking to expand, sized up the American market and used enthusiast magazines to help spread the word. Filed away in the Cycle World archives are letters from Dunstall, who would sit down at a typewriter and peck out correspondence to individual journalists, such as this one to CW Editor Ivan Wagar:

4th February, 1970

Dear Ivan,

herewith particulars of our 1970 Duns tall Nortons....

Dunstall Norton Sprint: This is designed as a pure fun bike for street use. It also features our fully prepared engine, which, allied to the bike s light weight (many light alloy and glassfiber parts being fitted) and if specified with the low, 4.84 gearing, becomes a really shattering abouttown performer....

Shattering is the right word. With a talented rider twirling the dials, a fullhouse Dunstall Norton could break into the 1 Is at the dragstrip, justifying the company’s “World’s Fastest Production Motorcycle” motto. Dunstall was also among the first to extol the virtues of disc brakes, going as far as to design his own twin-disc setup. He wrote to Jody Nicholas, CW Assistant Editor, detailing the highlights of the 1971 catalog:

24th December, 1970

Dear Jody,

...Our disc brake is not new, having been introduced early in 1970, but the incredible demand we have received for it proves the need for such an efficient and sophisticated unit. Many large motorcycle manufacturers have shown considerable interest in it, units having already been supplied to Ducati and BMW. Now an order has been received from Yamaha, who are the latest to show a keen interest in the unit....

It was with kitted Japanese bikes, first the Honda CB750, then various Suzukis and Kawasakis, that Dunstall hoped to convert America to cafe-racers. He couldn’t resist proselytizing in a letter to Wagar:

25th January, 1973

Dear Ivan,

regarding the Dunstall Honda 750. As you already know, the American market is showing every sign of moving strongly toward the “Cafe-Racer ” styling and approach. Providing this trend is handled properly, it will prove to be a good thing for motorcycling, getting rid of those unsafe choppers and replacing them with roadrace engineered and styled machines.

The suitability of cafe-racer styling, i.e. clip-ons, rearset footrests, fairings, etc., can best be gauged by the fact that, without exception, all leading motorcycle roadracers find these items of equipment necessary in the pursuit of speed and safety. If anyone has any doubts about this, they should try> asking Hailwood, Agostini or the like what they would think about their chances of lapping the Isle of Man at over 100 mph on a machine fitted with high handlebars and forward footrests....

Unfortunately for Dunstall, the fledgling U.S. cafe boom faded in the mid-1970s, replaced by cruisers, factory-done renditions of those “unsafe choppers” he so hated. A decade later, cafe-racers came back strong in the form of Honda Interceptors, Suzuki GSX-Rs, Yamaha FZs, etc. By then, Dunstall, a man ahead of his time, was out of business.

My Dunstall Honda is based on a 1976 CB750F. I bought it from my friend Randy Troy, who had been trying to sell it for at least two years without much interest. I told him to lop $1000 off the price and someone would buy it. Six months later, I was that someone. It carries Dunstall’s fiberglass half-fairing, tank cover, dual seat and blade-type front fender. A breathed-on motor of indeterminate displacement is hooked up to a Dunstall Decibel exhaust pipe. English Cambry cast wheels look the part, as do the S&W shocks and low handlebar. It’s a pretty good example of a mid-’70s cafe-racer, in need of an engine rebuild, a paint respray, new rubber and a general tidying-up.

All of which was on line until I decided to buy a house. Of course, everyone’s been telling me what a great tax write-off owning a home is.

Maybe there’s hope for the Dunstall, after all, courtesy the 1RS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsThat Critical First Ride

May 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMaybelline

May 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupSupermotard Strikes Again

May 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupDucati's Dynamic Duo

May 1994 By Adam Smallman -

Roundup

RoundupSpy Photo Reveals Bmw's New Standard

May 1994 By Robert Hough