BEAUTIFUL

ELEMENTS

Appreciating the motorcycle

KEVIN CAMERON

At the end of a recently published story, I asked the rhetorical question: Which was Massimo Tamburini, designer of Ducati’s 916: engineer or artist?

A trick question? Undoubtedly. Because of course it cannot be either/or; created objects can be simultaneously visually beautiful, beautiful in the manner of their function, and beautiful in their relation to how we live.

Once, years ago, when post-race tech inspection had finished after the Suzuki Cup at Road Atlanta, I was privileged to hear some free conversation among a few of the engine builders and crew chiefs, conversation that revealed some unconscious poetry of speech.

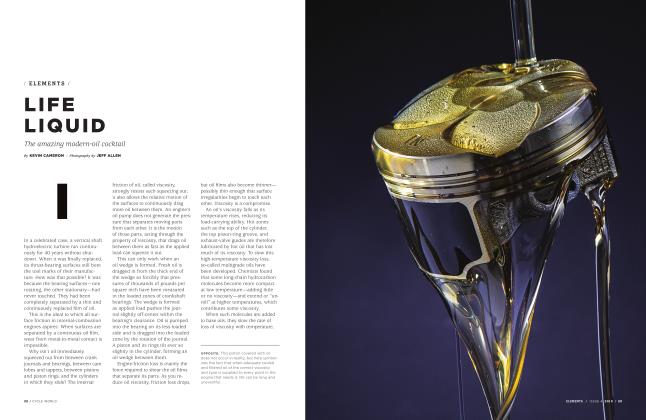

Yes, we all owed our employment to motorcycles, but our reasons for being there had little to do with the necessities of making mortgage and car payments. The hours spent measuring valve drops in engines trial-assembled with light checking springs were not that different from the hours the sculptor spends revealing a shape by removing stone chips with a hammer and chisel. When all the valve drops are right and final assembly takes place, the resulting beauty is unseen but real; a synchronized ballet as the pistons finish their exhaust strokes and chase the exhaust valves toward their seats, coming so close yet never ever touching, then accelerating downward, rapidly bounding as the intake valves awake from their repose.

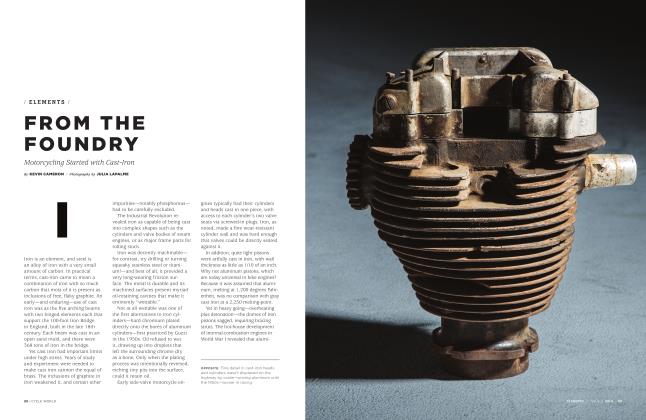

CARBURETORS AS SCULPTURE

Carburetors are now well obsolete, both technically and socially; inaccurate mixture formation reduces performance and increases emissions. Yet I find them beautiful even so. When my Kawasaki HI R triple engine was complete and in the frame, I would mount the up-angled carburetors, route and secure the throttle and choke cables, and synchronize slide lift. I liked the three bellmouths, gracefully shaped to invite airflow. I turned the throttle to see the slides lift together in harmony. There was hypnotic pleasure in all this.

The shape of an Amal GP carburetor, the type fitted to Manx Nortons and BSA Gold Stars, is undeniably functional. There is no extra metal, no “styling.” They are beautiful. Partly for what they have accomplished; how many seven-lap, 263-mile TTs, how many British short-circuit races of the 1950s and ’60s? And partly for their economical, purposeful shape, which has been part of such distinguished machines.

I loved also the “you can’t have it” exotic form of Keihin’s RS carbs, which I first saw up close on a mid’60s Honda Hawk twin that a US serviceman had brought back from Japan, and before that in pictures showing them on all those classic Honda GP bikes of that decade.

BEAUTIFUL BRAKES

From March 1972 onward, when I saw what they couldn’t do, I was done with drum brakes. But I still find attraction in their sand-cast textures, their cam-operating levers, their arrangements for cooling air. Discs are another matter altogether, as I was there to see modern practice emerge from “nice try but no cigar” to today’s impressive stoppers. Discs today are defined by what it takes to prevent their coning; they float on buttons or a T-drive to allow free heat expansion, radially narrow to reduce the difference in heating rate from OD to ID. They have the shape of success.

When I briefly encountered a ’90s Aprilia 250 two-stroke racer up close, I tried to bring together in my mind its European need for detailed hand assembly and the fluid Bird in Space shape of its exquisitely welded aluminum chassis. In stock as-received condition its two pistons came to top dead center at slightly different times. As with four-stroke valve drops, accuracy is entirely up to the individual involved in the assembly; there is no “insert tab A into slot C.” When you handle its empty fuel tank it is air. The bolted-on carbon seat frame feels like wood. Turning the engine by hand with carbs removed, I could see the leading edges of its rotary disc intake valves slice across the ports. Here was this exotic thing, an ocean’s distance from me in the 1960s, now right in my face.

What have Ducati engineers recently learned that caused Yamaha’s Fabio Quartararo to exclaim after the Misano MotoGP, “The lean angle [Francesco Bagnaia] had in turn 12! I said, ‘OK, I think it’s the moment to stay calm.’ ”

New knowledge that Ducati has put into Bagnaia’s chassis makes that lean angle possible. It will become part of future production Ducatis. Experiment mostly means failure, because wrong answers are numerous. When you get something right at last there is no better feeling in the world. It is beautiful.

“Make an ugly wheel and nature will break it.”

I still like the soft gleam of an aluminum rim on a wire-spoked wheel. But I have visited the Marchesini operation at Brembo and seen raw forgings become mag wheels. The forgings are ugly, puffy-looking, lumpy like risen bread. They disappear behind the closed doors of CNC lathes to become a stream of chips and the sculptures we use on our bikes. No old-world craftsmen here. Attend a race and you’ll see racks of these being pushed to and from the tire-busters. Their original unmarked perfection soon takes on the well-used look after a few tire changes. Eventually they are timedout scrap, unless connoisseurs contrive to spirit them and their undiscovered fatigue cracks away to temperatureand humidity-controlled collections. To be light and yet not crack they are given flowing organic shape: Make an ugly wheel and nature will break it.

Same with connecting, “The lean angle [Francesco Bagnaia] had in turn 12! I said, ‘OK, I think it’s the moment to stay calm.’ ” New knowledge that Ducati has put into Bagnaia’s chassis makes that lean angle possible. It will become part of future production Ducatis. Experiment mostly means failure, because wrong answers are numerous. When you get something right at last there is no better feeling in the world. It is beautiful. I still like the soft gleam of an aluminum rim on a wire-spoked wheel. But I have visited the Marchesini operation at Brembo and seen raw forgings become mag wheels. The forgings are ugly, puffy-looking, lumpy like risen bread. They disappear behind the closed doors of CNC lathes to become a stream of chips and the sculptures we use on our bikes. No old-world craftsmen here. Attend a race and you’ll see racks of these being pushed to and from the tire-busters. Their original unmarked perfection soon takes on the well-used look after a few tire changes. Eventually they are timedout scrap, unless connoisseurs contrive to spirit them and their undiscovered fatigue cracks away to temperatureand humidity-controlled collections. To be light and yet not crack they are given flowing organic shape: Make an ugly wheel and nature will break it. Same with connecting rods, high-strength bolts, power gearing, crankcases, chassis. The harder nature beats and strains against the things we make, the closer we come to discovering how to make parts that are beautiful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

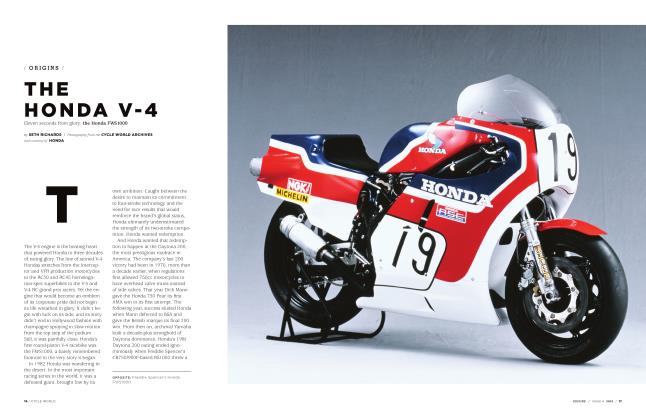

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTHE HONDA V-4

Issue 4 2021 -

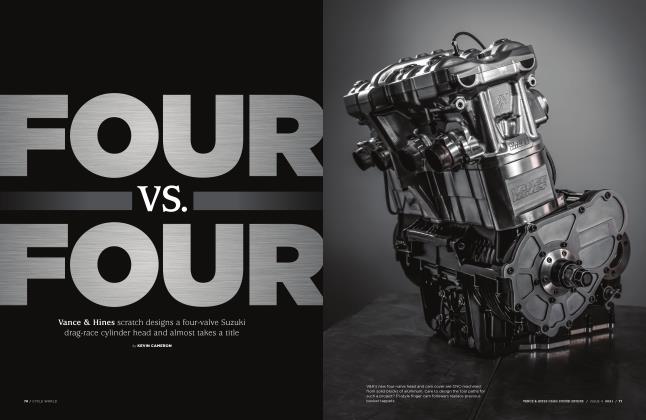

FOUR VS. FOUR

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

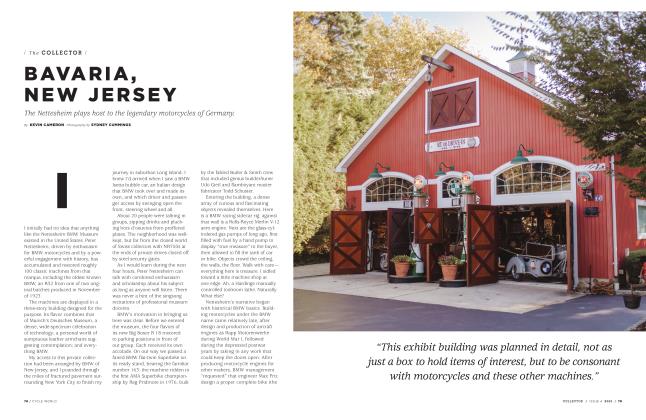

The COLLECTOR

The COLLECTORBAVARIA, NEW JERSEY

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

TDC

TDCHANDLING STRESS BY MOVING IT

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

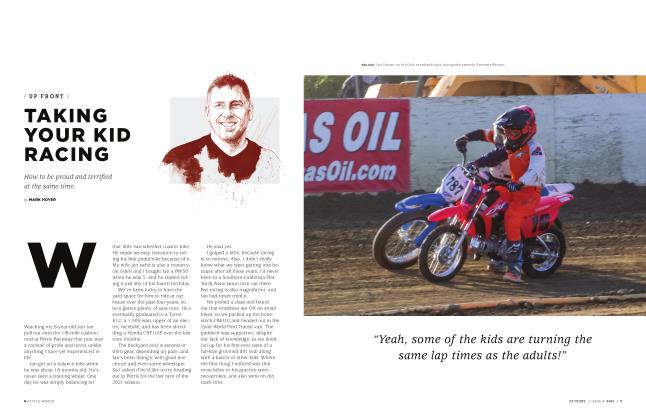

UP FRONT

UP FRONTTAKING YOUR KID RACING

Issue 4 2021 By MARK HOYER -

2022 APRILIA TUAREG 660

Issue 4 2021 By Justin Dawes