The trouble with teamwork

TDC

Kevin Cameron

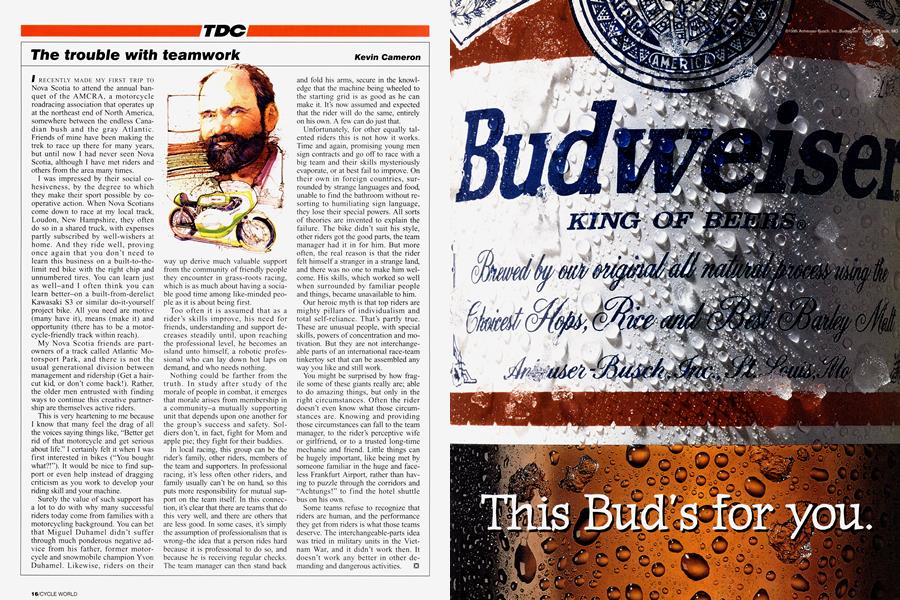

I RECENTLY MADE MY FIRST TRIP TO Nova Scotia to attend the annual banquet of the AMCRA, a motorcycle roadracing association that operates up at the northeast end of North America, somewhere between the endless Canadian bush and the gray Atlantic. Friends of mine have been making the trek to race up there for many years, but until now I had never seen Nova Scotia, although I have met riders and others from the area many times.

I was impressed by their social cohesiveness, by the degree to which they make their sport possible by cooperative action. When Nova Scotians come down to race at my local track, Loudon, New Hampshire, they often do so in a shared truck, with expenses partly subscribed by well-wishers at home. And they ride well, proving once again that you don’t need to learn this business on a built-to-thelimit red bike with the right chip and unnumbered tires. You can learn just as well-and I often think you can learn better-on a built-from-derelict Kawasaki S3 or similar do-it-yourself project bike. All you need are motive (many have it), means (make it) and opportunity (there has to be a motorcycle-friendly track within reach).

My Nova Scotia friends are partowners of a track called Atlantic Motorsport Park, and there is not the usual generational division between management and ridership (Get a haircut kid, or don’t come back!). Rather, the older men entrusted with finding ways to continue this creative partnership are themselves active riders.

This is very heartening to me because I know that many feel the drag of all the voices saying things like, “Better get rid of that motorcycle and get serious about life.” I certainly felt it when I was first interested in bikes (“You bought what?!”). It would be nice to find support or even help instead of dragging criticism as you work to develop your riding skill and your machine.

Surely the value of such support has a lot to do with why many successful riders today come from families with a motorcycling background. You can bet that Miguel Duhamel didn’t suffer through much ponderous negative advice from his father, former motorcycle and snowmobile champion Yvon Duhamel. Likewise, riders on their way up derive much valuable support from the community of friendly people they encounter in grass-roots racing, which is as much about having a sociable good time among like-minded people as it is about being first.

Too often it is assumed that as a rider’s skills improve, his need for friends, understanding and support decreases steadily until, upon reaching the professional level, he becomes an island unto himself, a robotic professional who can lay down hot laps on demand, and who needs nothing.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In study after study of the morale of people in combat, it emerges that morale arises from membership in a community-a mutually supporting unit that depends upon one another for the group’s success and safety. Soldiers don’t, in fact, fight for Mom and apple pie; they fight for their buddies.

In local racing, this group can be the rider’s family, other riders, members of the team and supporters. In professional racing, it’s less often other riders, and family usually can’t be on hand, so this puts more responsibility for mutual support on the team itself. In this connection, it’s clear that there are teams that do this very well, and there are others that are less good. In some cases, it’s simply the assumption of professionalism that is wrong-the idea that a person rides hard because it is professional to do so, and because he is receiving regular checks. The team manager can then stand back and fold his arms, secure in the knowledge that the machine being wheeled to the starting grid is as good as he can make it. It’s now assumed and expected that the rider will do the same, entirely on his own. A few can do just that.

Unfortunately, for other equally talented riders this is not how it works. Time and again, promising young men sign contracts and go off to race with a big team and their skills mysteriously evaporate, or at best fail to improve. On their own in foreign countries, surrounded by strange languages and food, unable to find the bathroom without resorting to humiliating sign language, they lose their special powers. All sorts of theories are invented to explain the failure. The bike didn’t suit his style, other riders got the good parts, the team manager had it in for him. But more often, the real reason is that the rider felt himself a stranger in a strange land, and there was no one to make him welcome. His skills, which worked so well when surrounded by familiar people and things, became unavailable to him.

Our heroic myth is that top riders are mighty pillars of individualism and total self-reliance. That’s partly true. These are unusual people, with special skills, powers of concentration and motivation. But they are not interchangeable parts of an international race-team tinkertoy set that can be assembled any way you like and still work.

You might be surprised by how fragile some of these giants really are; able to do amazing things, but only in the right circumstances. Often the rider doesn’t even know what those circumstances are. Knowing and providing those circumstances can fall to the team manager, to the rider’s perceptive wife or girlfriend, or to a trusted long-time mechanic and friend. Little things can be hugely important, like being met by someone familiar in the huge and faceless Frankfurt Airport, rather than having to puzzle through the corridors and “Achtungs!” to find the hotel shuttle bus on his own.

Some teams refuse to recognize that riders are human, and the performance they get from riders is what those teams deserve. The interchangeable-parts idea was tried in military units in the Vietnam War, and it didn’t work then. It doesn’t work any better in other demanding and dangerous activities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue