FOUR VS. FOUR

Vance & Hines scratch designs a four-valve Suzuki drag-race cylinder head and almost takes a title

December 1 2021 KEVIN CAMERONVance & Hines scratch designs a four-valve Suzuki drag-race cylinder head and almost takes a title

December 1 2021 KEVIN CAMERONFOUR VS. FOUR

Vance & Hines scratch designs a four-valve Suzuki drag-race cylinder head and almost takes a title

KEVIN CAMERON

Vance & Hines may not have won the 2021 NHRA Pro Stock Motorcycle series with Angelle Sampey and its new Andrew Hines-designed four-valve Suzuki cylinder head, but it came very close. Sampey, on the 1,850cc inline-four, was in the top three heading into the final round in Pomona, California. But when the tire smoke cleared, it was Matt Smith on an S&S “Buell” Vee-twin first, Sampey second, and Steve Johnson on a Monster four-valve Suzuki third. NHRA got the hoped-for value from legalizing four valves per cylinder on the long-serving GS-based Suzuki engine—a close, down-to-the-wire season that draws fans.

The long racing partnership between Vance & Hines and Harley-Davidson, and built-from-scratch “V-Rod” V-twin it produced, ended prior to the 2021 season. Vance &. Hines’ new sponsor in Pro Stock Motorcycle is Mission Foods.

The story of how an updated, machined-from-billet cylinder head came to sit on top of a now-ancient Suzuki engine case dates back decades. During the 1990s the two-valve-per-cylinder Suzuki engine emerged as the gold standard of NHRA Pro Stock, but then hit a development wall. Andrew Hines (his father Byron co-founded V&H with Terry Vance), said, “With its steep valve angle we were kind of stuck. More lift [which such a big engine needed] just hit the problem of valve-tovalve interference.”

.. they made a completely new head, CNC machined from billet, giving it as many beneficial changes as the rules allowed. ”

For Vance & Hines the solution was to make its own billet “Suzuki” head to remove the performance compromises.

Back in that era, the class was in trouble. The many Harley fans could hardly be expected to cheer as production-based thundering Milwaukee pushrod V-twins were smoked off by screaming Suzukis. What if someone were to design and build a pure racing engine machined from billet and conceptually transform it into a “Harley” by making it a Vee-twin with two huge pushrod-operated valves per cylinder? Two organizations stepped up with such designs. Vance & Hines was first in 2002 with its “V-Rod” 4.9 x 4.24-inch V-twin. S&S came a year later with its 5.125 x 3.875-inch “Buell,” both displacing the spec’d 160ci for V-twins. Neither engine contained any Harley parts, but that didn’t bother drag race fans. As Byron Hines once said, tongue-in-cheek, “If an Ilmor is a Mercedes, then this is a Harley.” (In 1994 an Ilmor pushrod engine, funded by Mercedes, won the Indianapolis 500.)

Why the huge displacement? The peak rpm of the billet twins is limited by their long strokes, so their monster displacement compensates for the Suzukis’ ability to rev to 14,000.

It is parity that keeps NHRA classes pulling spectators, seeking the performance equality that makes every win a surprise rather than a snooze. This requires periodic rules adjustments, with the Suzukis progressing from 1,500cc to 1,655, then 1,755, and now 1,850cc. Rules evolved for the billet twins as well; four valves, then two, and then “telephone poles for pushrods,” as rival Steve Johnson describes NHRA’s required 8-inch pushrods.

Displacement increases sound great, but the details get complicated. The original engine was 1,100cc with valves sized in proportion. Anyone who’s ever run a big-bore kit knows power doesn’t increase in proportion to the larger displacement. This is because the bigger engine is still sucking through the same-sized valves.

OK, you install bigger valves, but that makes them come really close to each other during valve overlap. And that puts limits on valve lift and timing. So you relocate the valves, farther apart.

Now we can again increase valve lift with a “big cam,” but taller cam lobes eventually overhang the edges of the inverted-bucket valve tappets, which were sized for street cams. Fortunately we have a bunch of CNC machines out in the shop, so now we bore out the tappet guides in the head to make room for—you guessed it—bigger-diameter tappets. But because the engine needs more air each time NHRA gives it a break, it eventually needs tappets too big for the existing casting. You’re stuck, as Andrew Hines said.

So they made a completely new head, CNC-machined from billet, giving it as many beneficial changes as the rules allowed. Vance & Hines had its new two-valve-percylinder Suzuki head ready for 1998.

“The Vee-twin guys learned to make a lot of power, but we couldn’t get the four-cylinder to progress,” Andrew Hines said. “This has been our livelihood forever, going back.”

I recalled seeing many Suzuki engines awaiting service in their Brownsburg, Indiana, shop, last time I visited.

In the 19-year billet V-twin era, the V&H/Harley combo has won 10 championships. With market changes now taking Harley-Davidson’s full attention, it has stood down from its partnerships with Vance & Hines in both Pro Stock drag racing and American Flat Track. Looking at the record, the billet V-twins have won four times as many Pro Stock championships as Suzuki-engined bikes. Therefore, in July 2019 a carefully worded letter was sent to the NHRA, asking them to approve a new four-valve cylinder head to have the narrowed valve angles of 22 degrees for intake and exhaust. NHRA accepted the proposal and work began on the new head. Andrew Hines would design it.

This was the opportunity to correct many of the shortcomings of the previous two-valve-per-cylinder head. First among them were its old-technology inverted-bucket tappets. More than once made bigger, and finally given a humped (“radiused”) top surface to further increase lift, they were replaced by lighter and more versatile Formula 1-style pivoted finger followers.

“The followers we use were already in use in another design,” Hines said. He went on to say that the bucket followers had required hard coating that could be a problem in itself—especially in the keying of the radius tappets, to keep them from rotating in their bores.

Once the prototype four-valve hardware was completed, a test engine was assembled.

“First day on the dyno, it surpassed our best twovalve,” Hines said. Their in-house airflow specialist gave the CNC-machined ports a touch-up. No further changes have been necessary.

For years, Pro Stock coverage has repeated the figure of 350 hp for the class. If we choose a respectable stroke-averaged net combustion pressure of 180 psi, and combine that with the 160ci of the billet twins and their 10,000 peak rpm, the numbers predict 363 hp.

Looking at photos of the new four-valve head, it is clear that the original no-downdraft intake angle has been preserved. Hines noted that this has been done to make it easier for users to adapt this head to their existing airboxes. But the intake and exhaust spigots (also CNC pieces) have been made separate from the head, allowing intake downdraft angle to be increased in future. Back when the Suzuki GS engines were first released, low intake angles were the norm because carburetors would dribble fuel from their idle systems if tipped up more than about 15 degrees. This gave those early literbike engines horizontal intake tracts that would fit entirely under the fuel tank. This has continued to the present in Pro Stock Suzukis.

In this century, the adoption of digital fuel injection has allowed intake port downdraft angle to be raised. To make this possible, the forward part of production-bike fuel tanks is now an intake airbox, displacing the fuel to the rear and in some cases into tank extensions under the rider’s seat. Hines’s use of replaceable intake spigots makes it possible, in the future, to explore the increased performance possible with such increased intake downdraft.

“We’re still using the original GS crank, a nine-piece crank that is pressed together,” Hines said. He went on to say that after assembly and alignment, the pressed joints are first pinned and then welded. This construction allows use of roller main and rod bearings.

When I asked about possible brittleness when welding high-carbon steel, he said they’d consulted with Lincoln Electric on the best rod for this critical job. The area of the weld is ground out to remove surface-hardened material so the weld can join the tough cores of the parts.

Back when the best available cranks were assembled from original Suzuki-made pieces, but with updated connecting rods, it was said that a team might get as few as four runs from a crank, spinning it to 13,500 rpm. If that sounds strange, consider that the engines of Top Fuel cars are torn down for inspection and rebuilt after every run.

Vance & Hines decided to get into the crank business itself, making its own crankshaft pieces to assemble, align, and weld in-house.

I asked if they made their own cams for the new four-valve head. “We make the cams but the lobes are ground by Comp Cams. That’s Billy Godbold’s outfit.” Yes, indeed, respected names in the valve-train business.

And the valves? “The intakes are in the mid-thirties [millimeters] and the exhausts are in the low thirties. Lift is 0.500 inch intake and 0.450 inch exhaust,” Hines said coyly.

I asked about pistons. With four valves and a narrowed valve angle, less deep clearance notches would be required.

“Yes, we also raised the ring lands up.”

Notching the piston crown to clear two big valves can come close to the back of the top ring groove, forcing it to be located farther down. Why worry? As combustion proceeds, a fair amount of fresh charge is forced at high pressure (like 1,200 psi) into the piston-ring crevice and into the volume between top ring land and cylinder wall. Trapped there, it cannot contribute to peak combustion pressure. How much is lost this way? Two percent!

I asked if he could see it on the dyno. “Yes, it’s small, but there’s a gain.”

Do you think about an engine with a one-piece crankshaft?

“I think about it every day,” Hines said. “For now, this is what we have, in the original GS crankcase. That sets a limit too.”

At present the 1,850cc displacement limit (112.8ci) has to spin hard to stay with the plump billet twins. If we do the arithmetic with that displacement, the 13,500 revs the Suzuki guys talk about, and the same cylinder filling, the guesswork number comes out as 384 hp.

Will the Suzukis move ahead in 2022, now that V&H has learned more about how best to apply this new kind of power? NHRA hopes that will be a surprise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

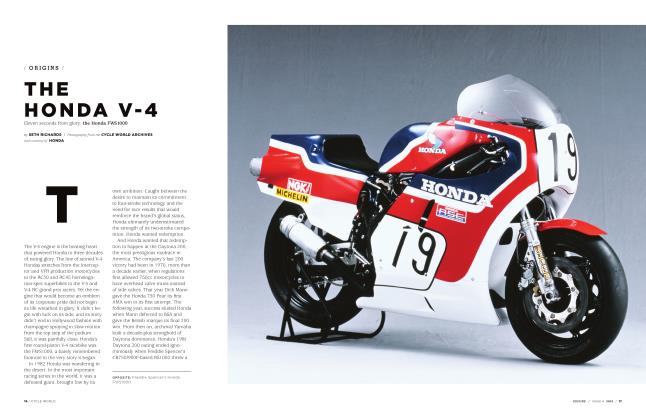

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTHE HONDA V-4

Issue 4 2021 -

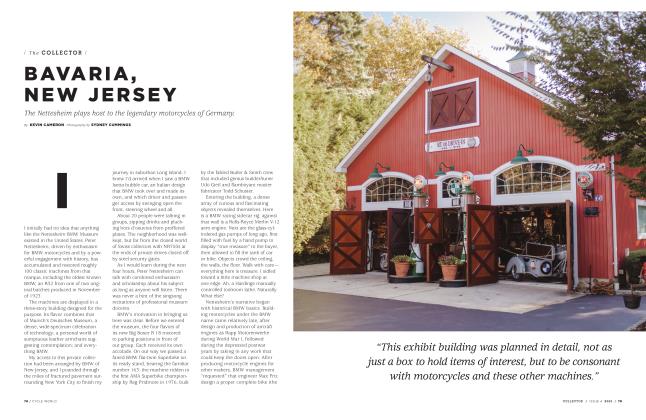

The COLLECTOR

The COLLECTORBAVARIA, NEW JERSEY

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

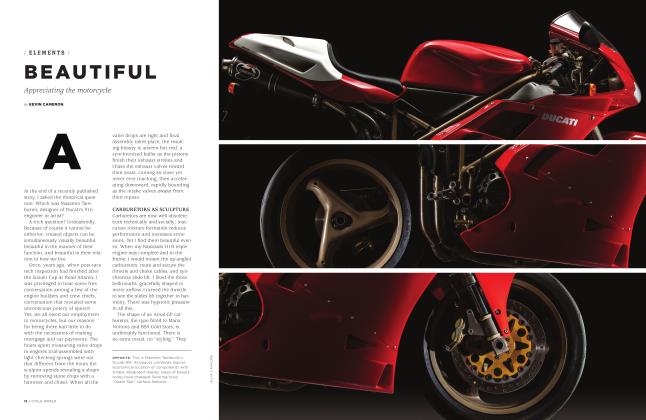

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSBEAUTIFUL

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

TDC

TDCHANDLING STRESS BY MOVING IT

Issue 4 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

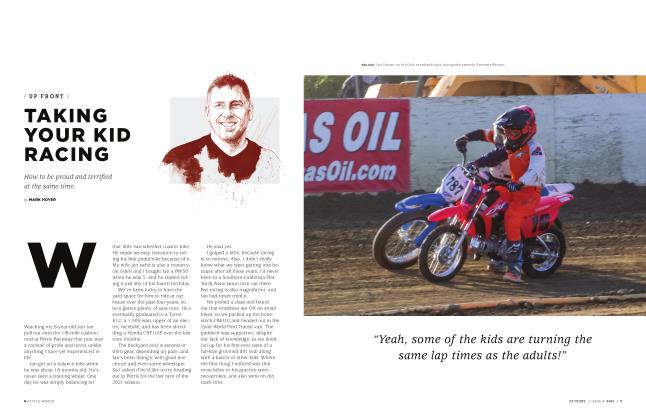

UP FRONT

UP FRONTTAKING YOUR KID RACING

Issue 4 2021 By MARK HOYER -

2022 APRILIA TUAREG 660

Issue 4 2021 By Justin Dawes