Legend of the Lost TD1

When Team CW took on the Isle of Man

For those lately come to motorcycling, two-strokes are mysterious, smoky devices from the past, presently hanging on by their hydrocarbon-stained fingernails in dirtbikes, but destined to follow the steam engine and the vacuum tube into obscurity.

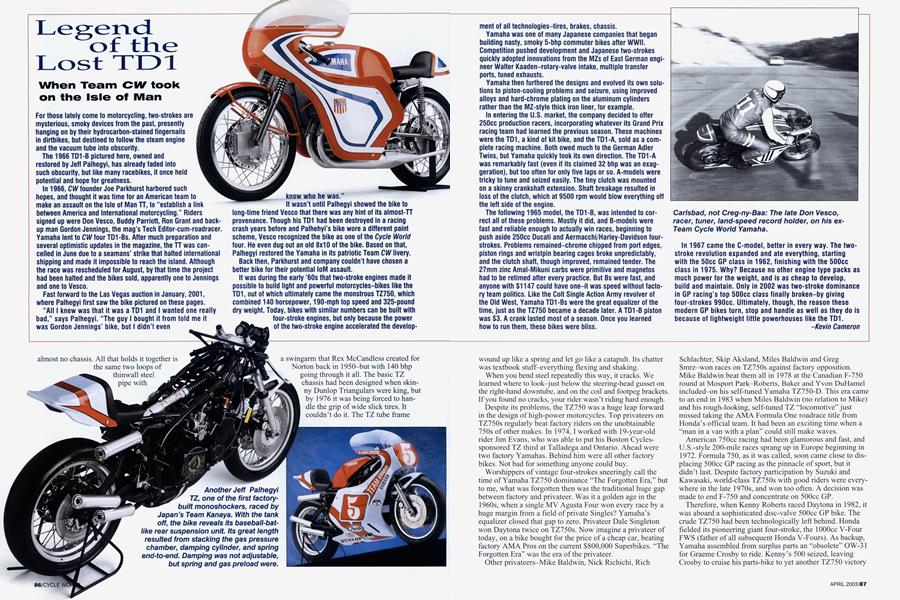

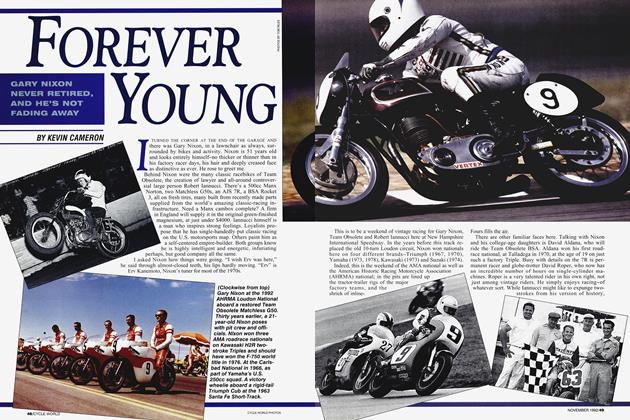

The 1966 TD1-B pictured here, owned and restored by Jeff Palhegyi, has already faded into such obscurity, but like many racebikes, it once held potential and hope for greatness.

In 1966, CW founder Joe Parkhurst harbored such hopes, and thought it was time for an American team to make an assault on the Isle of Man TT, to “establish a link between America and International motorcycling.” Riders signed up were Don Vesco, Buddy Parriott, Ron Grant and backup man Gordon Jennings, the mag’s Tech Editor-cum-roadracer Yamaha lent to CW four TD1-Bs. After much preparation and several optimistic updates in the magazine, the TT was cancelled in June due to a seamans’ strike that halted international shipping and made it impossible to reach the island. Although the race was rescheduled for August, by that time the project had been halted and the bikes sold, apparently one to Jennings and one to Vesco.

Fast forward to the Las Vegas auction in January, 2001, where Palhegyi first saw the bike pictured on these pages.

“All I knew was that it was a TD1 and I wanted one really bad,” says Palhegyi. “The guy I bought it from told me it was Gordon Jennings’ bike, but I didn’t even know who he was."

It wasn’t until Palhegyi showed the bike to long-time friend Vesco that there was any hint of its almost-TT provenance. Though his TD1 had been destroyed in a racing crash years before and Palhehyi’s bike wore a different paint scheme, Vesco recognized the bike as one of the Cycle World four. He even dug out an old 8x10 of the bike. Based on that, Palhegyi restored the Yamaha in its patriotic Team CW livery.

Back then, Parkhurst and company couldn’t have chosen a better bike for their potential loM assault.

It was during the early ’60s that two-stroke engines made it possible to build light and powerful motorcycles-bikes like the TD1, out of which ultimately came the monstrous TZ750, which combined 140 horsepower, 190-mph top speed and 325-pound dry weight. Today, bikes with similar numbers can be built with four-stroke engines, but only because the power of the two-stroke engine accelerated the development of all technologies-tires, brakes, chassis.

Yamaha was one of many Japanese companies that began building nasty, smoky 5-bhp commuter bikes after WWII. Competition pushed development and Japanese two-strokes quickly adopted innovations from the MZs of East German engineer Walter Kaaden-rotary-valve intake, multiple transfer ports, tuned exhausts.

Yamaha then furthered the designs and evolved its own solutions to piston-cooling problems and seizure, using improved alloys and hard-chrome plating on the aluminum cylinders rather than the MZ-style thick iron liner, for example.

In entering the U.S. market, the company decided to offer 250cc production racers, incorporating whatever its Grand Prix racing team had learned the previous season. These machines were the TD1, a kind of kit bike, and the TD1-A, sold as a complete racing machine. Both owed much to the German Adler Twins, but Yamaha quickly took its own direction. The TD1-A was remarkably fast (even if its claimed 32 bhp was an exaggeration), but too often for only five laps or so. A-models were tricky to tune and seized easily. The tiny clutch was mounted on a skinny crankshaft extension. Shaft breakage resulted in loss of the clutch, which at 9500 rpm would blow everything off the left side of the engine.

The following 1965 model, the TD1-B, was intended to correct all of these problems. Mostly it did, and B-models were fast and reliable enough to actually win races, beginning to push aside 250cc Ducati and Aermacchi/Harley-Davidson fourstrokes. Problems remained-chrome chipped from port edges, piston rings and wristpin bearing cages broke unpredictably, and the clutch shaft, though improved, remained tender. The 27mm zinc Amal-Mikuni carbs were primitive and magnetos had to be retimed after every practice. But Bs were fast, and anyone with $1147 could have one-it was speed without factory team politics. Like the Colt Single Action Army revolver of the Old West, Yamaha TD1-Bs were the great equalizer of the time, just as the TZ750 became a decade later. A TD1-B piston was $3. A crank lasted most of a season. Once you learned how to run them, these bikes were bliss.

In 1967 came the C-model, better in every way. The twostroke revolution expanded and ate everything, starting with the 50cc GP class in 1962, finishing with the 500cc class in 1975. Why? Because no other engine type packs as much power for the weight, and is as cheap to develop, build and maintain. Only in 2002 was two-stroke dominance in GP racing’s top 500cc class finally broken-by giving four-strokes 990cc. Ultimately, though, the reason these modern GP bikes turn, stop and handle as well as they do is because of lightweight little powerhouses like the TD1.

-Kevin Cameron