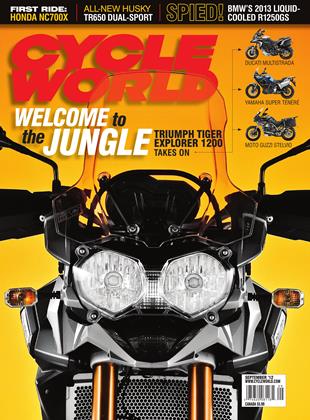

WORLD SUPERBIKE GROWS UP

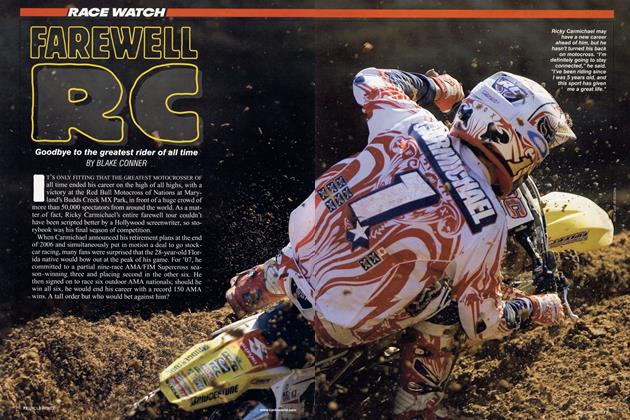

RACE WATCH

Twenty-five years of full grids, close racing and value for all involved

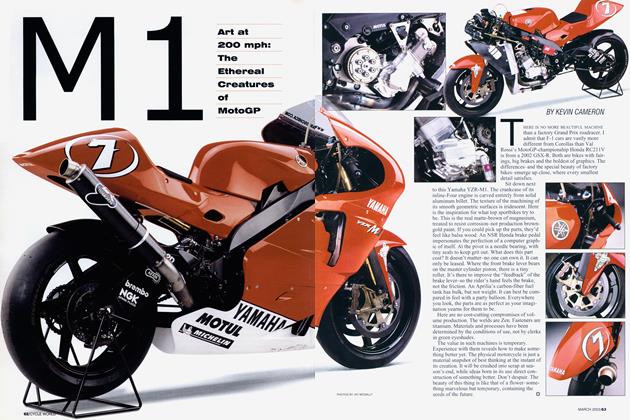

KEVIN CAMERON

WE GO TO THE RACES BECAUSE THAT’S where the information is. Isn’t there information at new-model introductions? Yes, but it’s different: rehearsed, polished, edited for effect. At the races, the people who are making the future of the motorcycle are confronting real problems, right in plain sight. That means raw intel is there for anyone who’s paying attention.

One of my goals in attending the U.S. round of the eni FIM Superbike World Championship at Miller Motorsports Park in Tooele, Utah, was to find out what BMW has done in the past year to transform its inline-Four from a disappointment that could lead five laps then fall back to 13th into a race-winner.

Also important was the opportunity for me to ask SBK Director Paolo Ciabatti how his series will respond to pressure from Spanish MotoGP rights-holder Dorna to slow down.

New CRT machines being used to pad out thin MotoGP grids are powered by SBK-spec, production-based engines but detuned in rpm and power to allow them to last two races each. Each time SBK has come close in performance to MotoGP, there has been concern over “keeping the grand in Grand Prix.” Never mind that the two series share few tracks, the principle has importance in both business and prestige.

My third goal was to watch the supporting AMA Pro races and assess whether the appearance of instability in that series is real or illusory. When racing kingpin, publisher and AMA trustee John Ulrich burned AMA Pro CEO David Atlas earlier this year in a threepart editorial on his website, roadracing world.com, many got the impression that conversation between the two men was over. Does this mean Ulrich knows something about the coming future that Atlas does not?

Since the AMA National in April at Road Atlanta, when I last talked with him, AMA Pro Technical Director of Competition Al Ludington speaks in a different key. At Road Atlanta, he said electronics are part of SuperBike, and teams wanting to compete must “roll up their sleeves” and learn how to manage today’s higher-tech bikes. At Miller, he sounded more like Ulrich, who warns of possibly unlimited software costs if electronics are not banned.

That brings up a red flag! Will Yamaha really quit the series, as it has allegedly said it will, if electronics are banned or severely limited? When the Daytona Motorsports Group took over AMA Pro Racing, top brass essentially said they were going to clean out all the “dead wood”—overprivileged manufacturers, mouthy riders and, by inference, motorcycle enthusiasts (who needs a few hundred whiny know-it-alls when the Infallible Plan will soon pack the stands with roaring mainstreamers?).

As we know, the first part of the plan worked a treat: Honda and Kawasaki left, top riders were gone for good and the whiny know-it-alls stayed away in droves. The second part—packing in mainstream fans, promoting rider personalities and creating “20 free-standing professional teams, each supported by a Fortune 500 corporation, with all of them making money”—did not occur.

The seasons since that first one (remembered for the safety car crossways on the Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca straightaway, invisible to approaching riders) have been a time of reassessment and licking of wounds. With an audible roar of plumbing, the original management team was flushed away, replaced by conciliatory, slightly apologetic men who have worked hard to restore function and credibility to the series. They have, I found at Road Atlanta this year, achieved a good deal.

But let’s have a look at BMW. Team director Bernhard Gobmeier drew an engine power curve, rising linearly from left to right, peaking then hooking over. Indicating the rising slope, he drew lines fattening it, saying, “Riders always want improvements here, but for Formula One, this has no importance because the engine is never there.” In our discussion, he revealed that all ports on the S1000RR have been made smaller, the combustion chambers have been reshaped, compression has been reduced slightly and control electronics “have been turned upsidedown.” Peak power has not been lost, but bottom and midrange gains have been achieved by moving the peak of intake delivery to lower revs through improved combustion and altered valve timing.

“Turning electronics upside-down” I take to mean that, while before, control strategies concentrated on the top of the band, now they work hardest to improve delivery from the bottom and midrange. Yamaha was at this point in MotoGP in 2007 and ’08, working to allow the rider to apply controllable power sooner in corners and be able to use more of it.

As BMW rider Marco Melandri put it, “Here, you are on full throttle maybe three seconds per lap, but you open the throttle from zero maybe 20 times per lap.”

Anybody remember the nothing... nothing.. .BAM! throttle characteristic of the first-year Yamaha YZF-Rl? Anyone facing that behavior soon learns to delay acceleration until the tire has enough grip to handle it. Meanwhile, the smooth Ducatis have oozed past on both sides. Maybe you can make the top 10. What BMW has learned is that a rac ing motorcycle needs a silky-smooth tractor engine with peak power. And they have delivered it. Melandri pointed out that in car rac

ing, it is from data that the engineers take their direction. With bikes, it is rider feeling, which is invisible on data. Cars have four massive tires, each of them planting 100 percent of their tread width on the track. Bikes have only two, and each tire presents only one third of its tread width to the pavement. Riders, given harsh power with peaks and valleys, can use only "the tip of the iceberg," for taking a handful just turns your faceshield into a gravel scoop.

When asked about Dorna pressure on SBK, Ciabatti replied that, while Bridgepoint Capital does own both World Superbike and MotoGP, each series is a part of a different fund owned by different groups of stockholders who expect a profit from their shares-not race series squabbling. SBK Technical Director Steve Whitelock said that indeed "pressure had been applied" at a recent meeting at England's Donington Park, but SBK managers had said their rules will re main constant for five years from 2013. Maybe it will be Dorna who has to roll up its sleeves. Next year, SBK machines will display decals simulating head lights and taillights, and 17-inch tires and aluminum wheels will replace pres ent magnesium 16.5s. Pirelli engineer Giorgio Barbier said, "When the 16.5s came in, there were sound technical advantages in their use. That is no longer the case.”

Over many years, I have seen SBK managed by consensus rather than edict. Whitelock walks into a team garage and says, “Okay, guys, I know you’re planning to bring that new gizmo of yours in a couple of weeks. But I also happen to know what the guys down in garage 17 have in mind if you do. It’s in their truck, ready. You might want to think about that.” He walks on.

So far this year, of the six brands competing in SBK, five have won races. That provides value to the teams, their manufacturers and their sponsors. How do they do it? “I give them what they need,” said Whitelock.

When we talked with Jonathan Rea last year, he despaired of achieving much until a new model appeared. Acceleration was poor and success elusive. This season, he and the Ten Kate Honda CBR1000RR are back in the thick of it. The teams lacking ride-by-wire were allowed to use it. The Ten Kate team’s “Department of Engines” developed the system, which by small throttle movements trims the peaks and fills in valleys. Result? Power so smoothed that riders can use more of it. This smoothing will also allow the engine, previously detuned to flatten its delivery, to be raised to a higher power level.

New rules also allowed BMW to use a crankshaft that is seven percent lighter than stock, which has helped vehicle maneuvering.

When teams see this consensus method working, that they are all “in with a chance,” they trust and embrace it. By contrast, the edicts flying out of the typewriter of Dorna CEO Carmelo Ezpeleta seem desperate, as if MotoGP’s situation is precarious, only sustained by constant corrective rules.

Wondering about stability, I spoke with Atlas. Clearly and concisely, he stated that what you see is what you get. Policy comes from him, and there are no plans to “imprison” U.S. riders by reducing SuperBike from 1000 to óOOcc, or to otherwise ban the future of the motorcycle.

Long-time observers of AMA roadracing remember that real power has always been invisible. We were introduced to a new, all-powerful “czar of racing,” whose word would be law. Now, we’ll see real action! Poof, he’s yanked off-stage by a shepherd’s crook around his neck, pulled by an unseen power. Who is that power? What does it/ he want? Because of this history, even if Atlas is the real power, the turbulence of controversy over electronics gives an impression of instability.

That made it refreshing when racing began. As so often at Miller, Carlos Checa on the Althea Ducati took the Race 1 lead and slowly, slowly pulled away. Perfect. The finish order was Checa, Max Biaggi (Aprilia) and Rea.

“Overall, I can say it was a very good race for me, a very hard race,” said Checa. “Our bike is more heavy, more difficult in the turns. Also, I am not the lightest guy. We must be [at] 100 percent against them.”

Next up: AMA SuperBike. The usual close contest between current champion Josh Hayes (Graves Yamaha) and titlerival Blake Young (Yoshimura Suzuki) did not occur. Hayes motored to win by 8 seconds, while Young, clearly having an off day, lost a struggle with Hayes’ teammate, Josh Herrin. Hayes, being his usual serious, thoughtful self, said, “I want to know what the new challenge is.”

When the thin tissue of racing perfection is ripped, it is revealed as the intense work that it is. In Race 2, as before, Checa took the lead after Tom Sykes’ fast Kawasaki ate its tire (it only took two laps this tinu Then came a long red flag for oil from Hin Aoyama’s crashed Honda and a restart.

Same again, but on Lap 5, Checa was down unhurt. Masters can make mistakes.

Carlos Checa's string of victories at Miller may give the impression that racing is easy. Reality is different. "Exiting the turn," the Spaniard said after his Race 1 win, "I open full gas and feel like my bike was a stick in the ground. Behind Marco, I was not able to keep his slipstream. I don't remember last year or the year before this difference in the straight."

Suddenly, it was a close contest of Rea vs. Melandri, with the Italian taking and then holding a lead at the end of the straight on the last lap. At the checkers, it was Melandri, Rea and Biaggi.

The fact that BMW has given Melandri 20 switch-accessible engine maps suggests it is making good developmental use of his MotoGP experience. He knows how racebikes should work. He wants 20 more such maps and uses them on a lap-by-lap or even corner-to-corner basis. He brought his own technical people with him to BMW.

Ciabatti referred to MotoGP as “the senior series,” tracing back to 1949.

On the contrary, SBK is now the senior series, operating with full grids for 25 years in the modern style of presenting racing as an entertainment business. MotoGP has existed in that form only since 2002. As MotoGP emits more and more rules (knocking out problems with paper rockets) and expects by 2014 to have everyone on lackluster CRTs, it appears desperate by contrast. Back when Peter Clifford was trying to get his Yamaha R1-based engine homologated for MotoGP, officialdom patiently explained why it could not be a prototype.

Today, that clear statement is “inoperative” as management backpedals to redefine “prototype” as whatever it says it is—in this case, a confusing cross between Moto2 and a slowed-down SBK.

Ciabatti described new SBK TV contracts for both Europe and Asia as “adding value to the series.” The paddock is not sibilant with angry whispering and suspicion. It seems stable and happy. Whitelock noted in particular the Pedercini team—a family business that has been in the series for 15 years and, although its machines are not frontrunners, one which makes money. It is, to borrow a phrase, “a freestanding professional team.”

We wish the other championships equal success. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

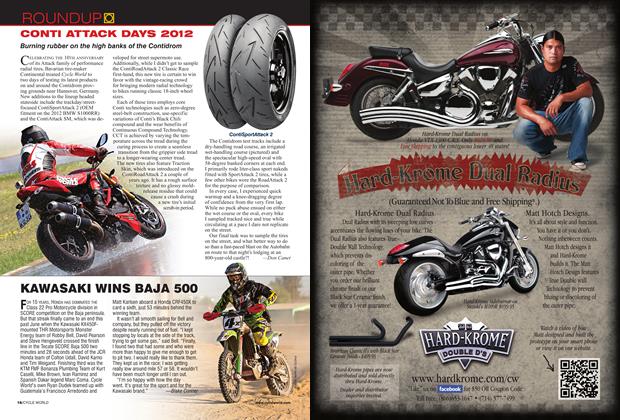

RoundupConti Attack Days 2012

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Don Canet -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1987

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! Lo Rider Concept

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Blake Conner -

Rolling Concours 2012

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupA Really Big Show

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer