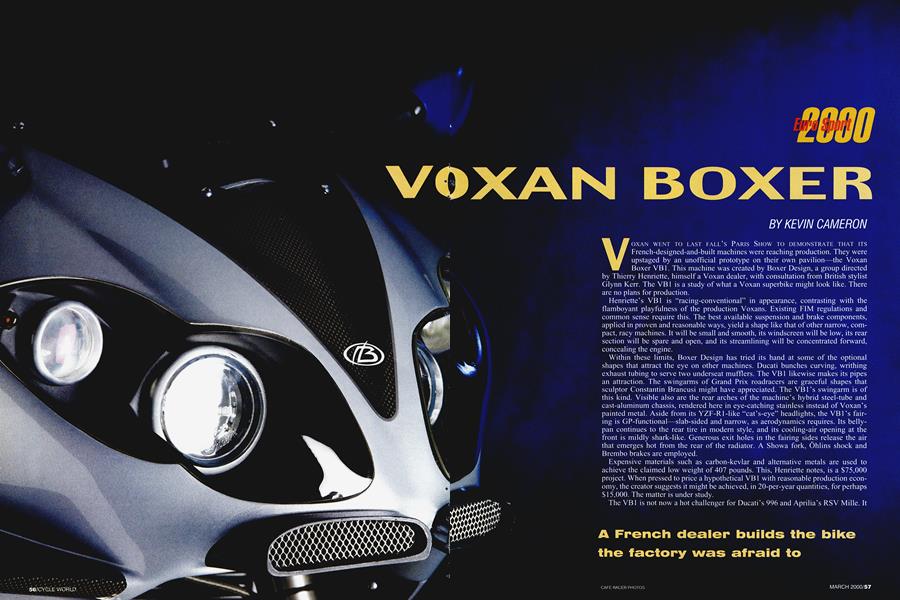

VOXAN BOXER

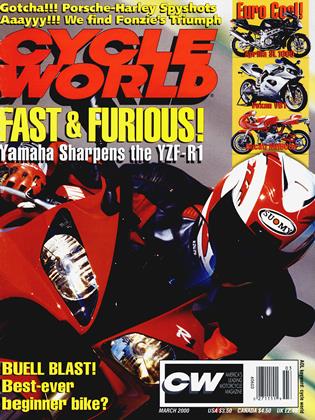

Euro Sport 2000

A French dealer builds the bike the factory was afraid to

KEVIN CAMERON

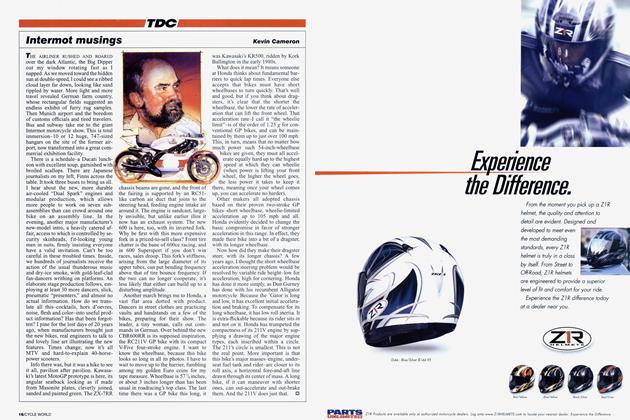

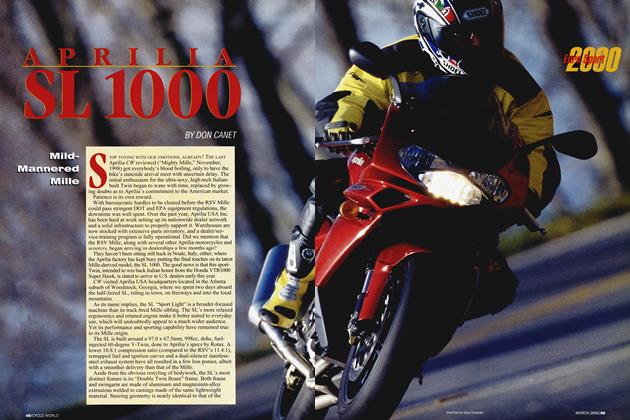

VOXAN WENT TO LAST FALL'S PARIS SHOW TO DEMONSTRATE TAHT ITS French-designed-and-built machines were reaching production. They were upstaged by an unofficial prototype on their own pavilion—the Voxan Boxer VB1. This machine was created by Boxer Design, a group directed by Thierry Henriette, himself a Voxan dealer, with consultation from British stylist Glynn Kerr. The VB1 is a study of what a Voxan superbike might look like. There are no plans for production.

Henriette’s VB1 is “racing-conventional” in appearance, contrasting with the flamboyant playfulness of the production Voxans. Existing F1M regulations and common sense require this. The best available suspension and brake components, applied in proven and reasonable ways, yield a shape like that of other narrow, compact, racy machines. It will be small and smooth, its windscreen will be low, its rear section will be spare and open, and its streamlining will be concentrated forward, concealing the engine.

Within these limits, Boxer Design has tried its hand at some of the optional shapes that attract the eye on other machines. Ducati bunches curving, writhing exhaust tubing to serve two underseat mufflers. The VB1 likewise makes its pipes an attraction. The swingarms of Grand Prix roadracers are graceful shapes that sculptor Constantin Brancusi might have appreciated. The VBl’s swingarm is of this kind. Visible also are the rear arches of the machine’s hybrid steel-tube and cast-aluminum chassis, rendered here in eye-catching stainless instead of Voxan’s painted metal. Aside from its YZF-Rl-like “cat’s-eye” headlights, the VBl’s fairing is GP-functional—slab-sided and narrow, as aerodynamics requires. Its bellypan continues to the rear tire in modem style, and its cooling-air opening at the front is mildly shark-like. Generous exit holes in the fairing sides release the air that emerges hot from the rear of the radiator. A Showa fork, Öhlins shock and Brembo brakes are employed.

Expensive materials such as carbon-kevlar and alternative metals are used to achieve the claimed low weight of 407 pounds. This, Henriette notes, is a $75,000 project. When pressed to price a hypothetical VB1 with reasonable production economy, the creator suggests it might be achieved, in 20-per-year quantities, for perhaps $ 15,000. The matter is under study.

The VB1 is not now a hot challenger for Ducati’s 996 and Aprilia’s RSV Mille. It is speculation, an elaborate message from one Voxan dealer to his manufacturer. Paris attendance figures show that 400,000 Frenchmen got that message.

Official Voxan spokesmen kept their distance from the VB1, insisting it was not their toe in the water, They must keep their heads down, get production up and make their shareholders happy before considering future projects.

Can we find the company’s ultimate intentions hidden in its engine design? Bore and stroke at 98 x 66mm are the same as those of Ducati’s 996 and the new Japanese liter-Twins. Double overhead cams driven by Hyvo chains operate four large valves per cylinder. Combustion chambers are compact as a result of the very narrow 21-degree incl▬uded valve angle. Short-skirted, Formula Onestyle pistons are used, with titanium connecting rods. Engine Veeangle is a compromised 72 degrees—between the 90 that cancels primary imbalance and the 60 that cancels secondary vibration,

No balancer shaft is used and engine management is by Marelli.

Don’t be fooled by the claim of 100 crank horsepower—20 or more down on other sportTwins—this is no cruiser. It is a high-performance engine strangled to meet French law. It can make more power when and if the need arises. The VB1 shows how it might look in this role. Let us hope its day will come.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue