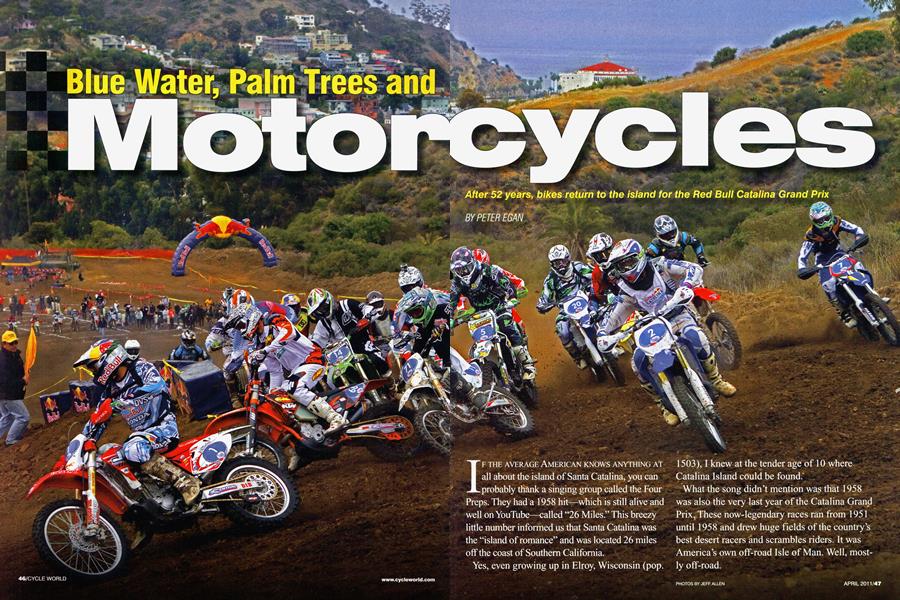

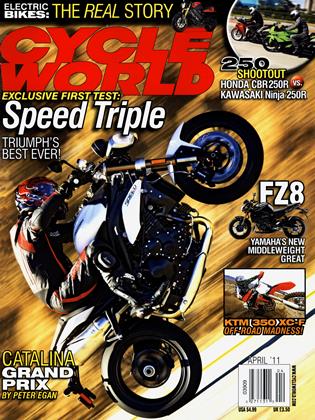

Blue Water, Palm Trees and Motorcycles

After 52 bikes return to the island for the RRed Bull Catalina Grand Prix

PETER EGAN

IF all THE about AVERAGE the island AMERICAN of Santa KNOWS Catalina, ANYTHING you can AT probably thank a singing group called the Four Preps. They had a 1958 hit—which is still alive and well on YouTube—called “26 Miles.” This breezy little number informed us that Santa Catalina was the “island of romance” and was located 26 miles off the coast of Southern California.

Yes, even growing up in Elroy, Wisconsin (pop. 1503), I knew at the tender age of 10 where Catalina Island could be found.

What the song didn’t mention was that 1958 was also the very last year of the Catalina Grand Prix, These now-legendary races ran from 1951 until 1958 and drew huge fields of the country’s best desert racers and scrambles riders. It was America’s own off-road Isle of Man. Well, mostly off-road.

“We walked up the street to the edge of town, where a football practice field, dubbed ‘The Field of Dreams,’ was serving as the weekend’s paddock area. Hundreds of bikes, all lined up in groups. It seemed that anybody who ever accomplished anything with a dirtbike could be seen walking around the paddock.”

The races started on the paved streets of Avalon—the picturesque little resort town on the island—and then climbed for 10 miles into the surrounding mountains on dirt fireroads and goat trails before they came blazing back into the streets of Avalon for the next lap.

It was a tough race—more than three hours of riding—and to win Catalina was a big deal. Walt Fulton won the first GP and Bob Sangren the last two. Meanwhile, future stuntman and Steve McQueen stand-in Bud Ekins won bigtime in 1955 on his Triumph Trophy, finishing more than 10 minutes ahead of the next rider. Movie stars such as Keenan Wynn and Lee Marvin also showed up and raced. It was a glamorous and prestigious event.

So, what killed it off?

I’d always read that the race had gotten “too big,” but this seemed to be code for something else. I talked to several ,race veterans at this year’s event, and they said it was mostly a matter of biker gangs showing up—those who do not ride so much as drink. (Ah, yes, the Wild One years. Thank you, Marlon Brando.) The mayor of Avalon was hit over the head and mugged at the races in 1958, and that was pretty much that.

Or so we thought.

When my wife Barb and I lived in California during the Eighties, we used to fly a rented Cessna over to the mountaintop airport on Catalina and have buffalo burgers for lunch at the airport café, or backpack down through the buffalo herds on the old Wrigley family ranch (yes, the Wrigleys of chewing gum and Chicago Cubs fame) and go camping on the beach.

On these trips, I’d always think what a great place this would be for another motorcycle race but held out little hope, what with modern environmental and liability problems. The Wrigleys had ceded most of the land to the Catalina Island Conservancy, which was more focused on wilderness preservation and hiking than race promotion. Also, very few cars are allowed on the island, and most residents drive golf carts. It was hard to imagine motorcycles being welcomed back to the pedestrian-friendly resort town of Avalon.

But tourism can always use a little boosting these days—particularly in the off-season period following the famous Catalina Jazz Festival—and this impulse jibed nicely with one motorcyclist’s lifelong dream of resurrecting the race. An energetic visionary named Vinnie Mandzak (of My Cuz Vinnie Promotions) held meetings with the city, the Conservancy, the Wrigley’s Island Company and the AMA’s District 37—who puts on the Big 6 Grand Prix Series—and together they configured a race course that made everybody happy. A December, 2010, race date was settled upon. All that was needed was a major sponsor, and Red Bull stepped up to the plate.

The Internet went nuts with speculation and desire. Eight hundred riders registered almost immediately for 12 races to be held over two days—the main event being a two-hour GP for pro riders. There would be races for vintage and modern bikes, riders of all age groups. All you needed was desire, a $250 entry fee, previous racing experience and an AMA license.

Bikes—-with their gas tanks empty— would be shipped over in containers from the Los Angeles Harbor in Wilmington. Fuel would be provided on the island, as would tools. No one was allowed to start an engine or ride unless heading for the starting grid, and there would be no practice or sighting laps permitted.

It all sounded too good to be true, so I quickly booked airline tickets from Wisconsin to Orange County and reserved a room at a place called the Atwater Hotel. The desk clerk said I was getting one of the last two rooms on the island—no heat, air conditioning or ocean view. “I’ll take

it,” I said. My principal need in any hotel is simply horizontalness.

A week later, I was standing at the docks in Newport Beach, California, waiting on a chilly Friday morning to board a ferry called the Catalina Flyer.

I was joined by our Associate Editor, Mark Cernicky, who had entered the race with a brand-new Kawasaki KX250F testbike—which he’d never ridden. Like almost everyone else on the boat, he showed up with a huge gearbag on rollers. The place looked like an Ogio convention, with KTM orange the dominant color rolling down the boarding ramp. Dirt riders go to sea!

In Arthurian legend, Avalon is the island to which King Arthur was taken after being mortally wounded at the battle of Camlann. He summoned a boat out of the mists by throwing his famous sword, Excalibur, into the water. Three mysterious and beautiful queens tended to his wounds on the voyage to the island.

Unfortunately, I had only Cernicky for company, but at least we did run into a strangely mystical fog bank about halfway to Catalina, emerging into sunlight just as the boat pulled into Avalon Harbor. Suddenly, we could see the famous Casino and Mediterranean-like cluster of homes and shops around the harbor. I had the odd feeling we’d gone through a time warp. And we had, in a sense. The motorcycles were back, after 52 years—even if we couldn’t see any. Or hear them. That would come later.

We all disembarked and walked to our various hotels, the small wheels of all those gearbags rattling on the brick streets like horse-drawn cabs in a Sherlock Holmes episode. I hadn’t been in Avalon for about 22 years, and I’d forgotten what a beautiful little town it is, compact and charming. I checked into the Atwater and found my room much better than expected—with a view of the harbor, after all. Palm trees, sun, blue water. Nice people running the place, too. Back home, it was snowing.

Mark signed in at the Hotel Metropole’s race registration desk, and then we walked up the street to the edge of town, where a football practice field, dubbed “The Field of Dreams,” was serving as the weekend’s paddock area. Hundreds of bikes, all lined up in groups. Classic Triumph Twins and Tiger Cubs, BSA Victors, red Huskys, AJS Singles, Honda XRs, Elsinores, etc. Beyond that, row upon row of modem bikes, some for the likes of Travis Pastrana, Johnny Campbell, Kendall Norman.. .and Cycle World's own Ryan Dudek, who was checking over his KTM 350 SX-F.

“Our Ryan Dudek didn’t do too badly, either, winning his Veteran +30 Heavy-weight A class by a huge margin. By the end of the race, he was so far ahead I wondered if the rest of the field had stopped for lunch.”

It seemed to me that anybody who ever accomplished anything with a dirtbike could be seen walking around the paddock. I ran into the great Danny LaPorte, and Malcolm Smith was there, Grand Marshal Bob Sangren.. .and Preston Petty, who invented the plastic fender for dirtbikes, probably right after Dave Ekins’ fenderless bike blasted him with gravel. There was a picture of this about to happen in the race program.

We hiked up to the start/finish line, which was on a motocross-type course just up a steep hill from the paddock, and this led to another motocross course higher up the valley. From there, the bikes would head into the hills on single-track trails and fireroads. There was a short paved section near the golf course, but the rest of every lap would be pure dirt. There’d be no racing through the streets of Avalon this time, just a parade lap before each race.

Nevertheless, this was no watereddown substitute for the old Fifties race circuit; it was the real deal—convoluted, varied, long and challenging. Vinnie told me a Catalina islander/racer/bulldozer operator named Phil “Buddy” Minuto had been busy for weeks, laying out the course, grading and grooming it. On the high trails clinging to the mountainside, skull & crossbone signs marked corners where you didn’t really want to go off. (To appreciate this, you must watch Dudek’s helmet-cam lap on our website, www. cycleworld. com. )

That evening, we went to a rider’s party at the Descanso Beach Club, right on the water (as so many beaches are), for food and drink, and Vinnie later got up to talk. He reviewed the race schedule, then dropped his usual humorous banter to make a short but quite impassioned speech. He asked the riders to treat everybody and everything on the island with respect. Then, he said, we might be invited back.

If that isn’t a message for the ages, I don’t know what is.

In the morning, I went down to the waterfront and watched the first great wave of bikes pour through the inflatable Red Bull arch and flood the streets on their way to the starting line—all vintage machines for Race 1. Some gray hair under the helmets and paunchiness of jersey, but also much youth aboard the great old bikes—Thumpers, Twins and two-strokes all blending into beautiful music. It looked like the Running of the Bulls in Pamplona, only with no goring or trampling. Riders had been warned under pain of death away from burnouts or wheelies.

People I’d talked to in the paddock rode by—Thad Wolff on his beautiful 1958 BS A 650 Super Rocket, an elegant Yoshi Kosaka on his vintage Yamaha Twin and perhaps the most enthusiastic competitor of the weekend, Frenchman Dimitri Coste, who’d brought his 1967 Triumph TR6C all the way from Paris, where he rides it on the street. He’d had a set of vintage-looking white leathers made just for Catalina. His bike got stuck in customs for five days, and he’d made his boat by just minutes.

As the bikes headed up the hill to start/finish, so did the crowds on the street. I got there in plenty of time to see the flag drop.

I wasn’t actually around for the Oklahoma Land Rush (even if I do remember the “26 Miles” song), but that’s what it looked like to me when the first wave of the 110-bike field charged up the hill to the first hairpin—a steep and slightly silty corner where several people fell down in every race. Back down the hill, up again, across to another short section with jumps, then up the hill to the second motocross course.

When you haven’t been to a true GP in a while, you forget how nice it is to stand in a natural setting close to the track, watching bikes slide, wheelie and thunder by. You’re well out of crash trajectory, but the bikes are right there, almost within reach. In today’s litigious world, most motorsports events keep you so far away from the action you almost can’t remember why you came. At Catalina, you could see talent happening just a few feet away. And there were endless good places to stand and watch.

For the next race, I hiked up the hill to the second motocross area and was delighted to find a big jump with a mud bog and a sharp comer on the other side—a good spot to watch riders who’d never been around the track react and figure out what to do next. Many of the fastest guys landed in the mud just once, then went around the jump entirely on the second lap, skimming along the inner fence, like Malcolm Smith at Elsinore in On Any Sunday. Fast learners.

One of those fast learners was Cernicky. Despite sliding out on the first hairpin, he picked up his Kawasaki in about 2.4 seconds and went on to lead his Senior Lightweight B race. Until he mistakenly waved second-place rider Ed Paulsen into the lead on the last lap, thinking Paulsen was in a faster class. Nevertheless, Mark earned a secondplace trophy about the size of the Taj Mahal, so he had a good day.

Dudek didn’t do too badly, either, winning his Veteran +30 Heavyweight A class by a huge margin. By the end of the race, he was so far ahead I wondered if the rest of the field had stopped for lunch. Believe it or not, I’d never before seen Dudek race in the dirt, and I quickly developed a whole new respect for the relentless speed and smoothness of his riding. And he passed people so politely they hardly knew what was happening to them until he was gone. (“Hey, where’s my watch and billfold!”)

Late in the afternoon, I’d hiked myself into a state of fatigue and realized I hadn’t eaten or drunk anything all day. Cute little Red Bull girls to the rescue. They came strolling by with backpacks full of 12-ouncers, and I downed one as if adding a quart of oil to an old truck.

Ten minutes later, I was doing one-armed pushups for my own amusement, ready to party for the rest of the evening.

And so we did, but modestly, as there were races the next day. Cernicky, Dudek, photographer Jeff Allen and I had some Mexican food (twin trophies towering at the center of our table), then walked along the Harbor to the white, shining radiance of the grand old Casino, where the stunt movie Nitro Circus! was being shown, all proceeds going to the Island Motorcycle Club’s youth program. Fortunately for those youth, the show was sold out, so we retired to a quiet bar where Cernicky advised us on the finest rums of the Caribbean and several other places.

Sunday dawned a bit overcast, with the threat of light rain, but the races were as good as the day before. Maybe better, because riders who entered multiple classes had now learned the circuit. After a morning of warm-up races—which included mere children who can ride better than I ever will—the Big Guns came out for the Pro race, the two-hour GP.

You could tell the game was afoot because a Huey camera helicopter began thumping overhead, getting ready to film the start for Dana Brown’s upcoming On Any Sunday III. (That’s me, standing along the fence, buying a hot dog from the Boy Scouts and swilling another Red Bull.)

cycleworld.com/catalinagp

Off went the 78 pros in three explosive waves, chasing their share of the $5000 purse, and I found it hard to believe we were watching this level of racing without having paid admission. Yes, you had to pay for your boat ticket to Catalina, and a hotel, but the races were free to the public! As tourist entertainment, it sure beat shopping for postcards.

Kurt Caselli pulled out a strong, early lead, riding like someone possessed until his engine let go, and then Kendall Norman—four-time Baja 1000 winner—took the lead and held it to the end. Travis Pastrana, who was one of the crowd favorites (both on track and in the autograph lines) ran near the front and was in third for a while until he also retired with engine problems. Sean Collier rode up through the pack to finish a stunning, hard-won second, just ahead of Colton Haacker.

And our young Dudek? Starting in the second wave with the +30 riders, he pulled away from his own field again and sped through the pack of younger pros, finishing fourth overall and narrowly missing the podium.

By the end of the day, a light rain was falling, but not enough to bother the racers or spectators much. After Cemicky (fourth in his Sunday 250 B class race) and I boarded our Catalina Flyer for the voyage home, however, it began raining in earnest, and the evening turned dark and nasty. We watched through rainstreaked cabin windows as the Christmas lights of Newport Harbor hove closer and Catalina disappeared into the darkness, but the GP had come off in a nearperfect window of December weather— not too hot, not too cold.

Everything else was good, too. In all this intense racing, there was only one serious injury the entire weekend—a veteran rider who dropped his bike, and then accidentally stepped in front of another rider. He was med-flighted away with broken ribs and a few other contusions.

Local reaction was almost too good to be true. The Catalina Islander newspaper published letters from local citizens— most of whom hadn’t known what to expect—praising the politeness of the motorcycle crowd and the surprising excitement of the races. This was a twoway street, as every rider and spectator I talked to (40 percent of whom had never visited the island before) said the islanders couldn’t have been more helpful or friendly. Frankly, I’ve never seen a race crowd so blissed-out and happy to be anywhere in my life. If I had a nickel for every time someone said, “Can you believe this is really happening?” I could buy out the Wrigleys.

Catalina was the Complete Package: superb motorcycle racing on a beautiful island with a scenic village, rugged mountains and friendly natives. And only 26 miles offshore—which makes it the closest off-road race for anyone living in Los Angeles.

I hope—to borrow from Bogart at the end of Casablanca—this is the beginning of a beautiful relationship, all over again. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIboty

APRIL 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupDakar 2011, Street's View

APRIL 2011 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley-Davidson Blackline Fxs

APRIL 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Victory High Ball

APRIL 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago April 1986

APRIL 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupDisaster Averted

APRIL 2011 By Kevin Cameron