The Captive Enfield

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

IT’S A QUIET WINTER DAY TODAY WITH snow drifting down in big dreamy flakes, like the ones we made with scissors and folded construction paper in Miss Podruch’s third-grade class and then plastered to the classroom wall with our names written on them. (“Why would anybody name a defective snowflake Pete?”)

Anyway, the snow is piling up, so of course I did what anyone would do on a day like this and retired to the garage with a cup of coffee to look at my stationary bikes and ponder Man’s fate in the encroaching Ice Age.

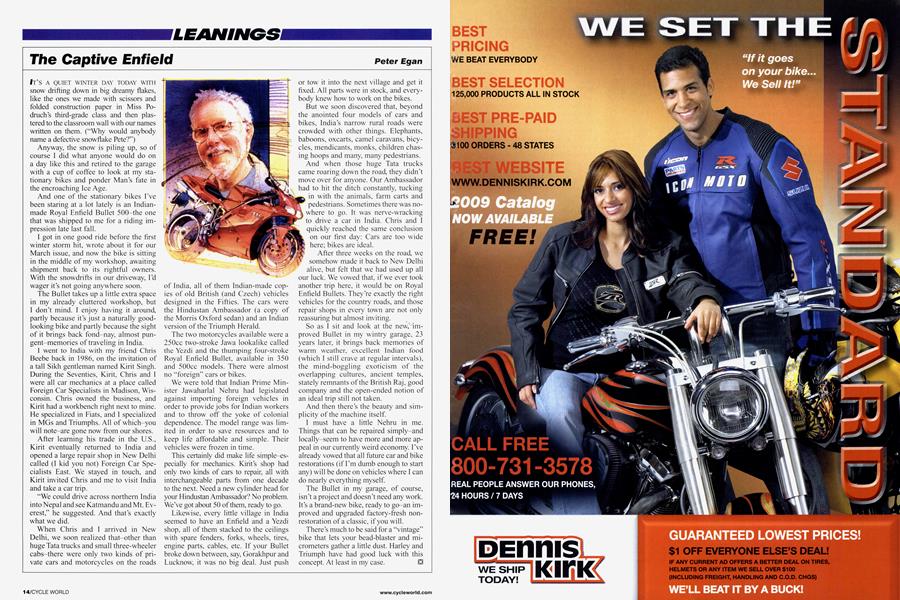

And one of the stationary bikes I’ve been staring at a lot lately is an Indianmade Royal Enfield Bullet 500-the one that was shipped to me for a riding impression late last fall.

I got in one good ride before the first winter storm hit, wrote about it for our March issue, and now the bike is sitting in the middle of my workshop, awaiting shipment back to its rightful owners. With the snowdrifts in our driveway, I’d wager it’s not going anywhere soon.

The Bullet takes up a little extra space in my already cluttered workshop, but I don’t mind. I enjoy having it around, partly because it’s just a naturally goodlooking bike and partly because the sight of it brings back fond-nay, almost pungent-memories of traveling in India.

I went to India with my friend Chris Beebe back in 1986, on the invitation of a tall Sikh gentleman named Kirit Singh. During the Seventies, Kirit, Chris and I were all car mechanics at a place called Foreign Car Specialists in Madison, Wisconsin. Chris owned the business, and Kirit had a workbench right next to mine. He specialized in Fiats, and I specialized in MGs and Triumphs. All of which-you will note-are gone now from our shores.

After learning his trade in the U.S., Kirit eventually returned to India and opened a large repair shop in New Delhi called (I kid you not) Foreign Car Specialists East. We stayed in touch, and Kirit invited Chris and me to visit India and take a car trip.

“We could drive across northern India into Nepal and see Katmandu and Mt. Everest,” he suggested. And that’s exactly what we did.

When Chris and I arrived in New Delhi, we soon realized that-other than huge Tata trucks and small three-wheeler cabs-there were only two kinds of private cars and motorcycles on the roads

of India, all of them Indian-made copies of old British (and Czech) vehicles designed in the Fifties. The cars were the Hindustan Ambassador (a copy of the Morris Oxford sedan) and an Indian version of the Triumph Herald.

The two motorcycles available were a 250cc two-stroke Jawa lookalike called the Yezdi and the thumping four-stroke Royal Enfield Bullet, available in 350 and 500cc models. There were almost no “foreign” cars or bikes.

We were told that Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had legislated against importing foreign vehicles in order to provide jobs for Indian workers and to throw off the yoke of colonial dependence. The model range was limited in order to save resources and to keep life affordable and simple. Their vehicles were frozen in time.

This certainly did make life simple-especially for mechanics. Kirit’s shop had only two kinds of cars to repair, all with interchangeable parts from one decade to the next. Need a new cylinder head for your Hindustan Ambassador? No problem. We’ve got about 50 of them, ready to go.

Likewise, every little village in India seemed to have an Enfield and a Yezdi shop, all of them stacked to the ceilings with spare fenders, forks, wheels, tires, engine parts, cables, etc. If your Bullet broke down between, say, Gorakhpur and Lucknow, it was no big deal. Just push

or tow it into the next village and get it fixed. All parts were in stock, and everybody knew how to work on the bikes.

But we soon discovered that, beyond the anointed four models of cars and bikes, India’s narrow rural roads were crowded with other things. Elephants, baboons, oxcarts, camel caravans, bicycles, mendicants, monks, children chasing hoops and many, many pedestrians.

And when those huge Tata trucks came roaring down the road, they didn’t move over for anyone. Our Ambassador had to hit the ditch constantly, tucking in with the animals, farm carts and pedestrians. Sometimes there was nowhere to go. It was nerve-wracking to drive a car in India. Chris and I quickly reached the same conclusion on our first day: Cars are too wide here; bikes are ideal.

After three weeks on the road, we somehow made it back to New Delhi alive, but felt that we had used up all our luck. We vowed that, if we ever took another trip here, it would be on Royal Enfield Bullets. They’re exactly the right vehicles for the country roads, and those repair shops in every town are not only reassuring but almost inviting.

So as I sit and look at the new, improved Bullet in my wintry garage, 23 years later, it brings back memories of warm weather, excellent Indian food (which I still crave at regular intervals), the mind-boggling exoticism of the overlapping cultures, ancient temples, stately remnants of the British Raj, good company and the open-ended notion of an ideal trip still not taken.

And then there’s the beauty and simplicity of the machine itself.

I must have a little Nehru in me. Things that can be repaired simply-and locally-seem to have more and more appeal in our currently weird economy. I’ve already vowed that all future car and bike restorations (if I’m dumb enough to start any) will be done on vehicles where I can do nearly everything myself.

The Bullet in my garage, of course, isn’t a project and doesn’t need any work. It’s a brand-new bike, ready to go-an improved and upgraded factory-fresh nonrestoration of a classic, if you will.

There’s much to be said for a “vintage” bike that lets your bead-blaster and micrometers gather a little dust. Harley and Triumph have had good luck with this concept. At least in my case.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

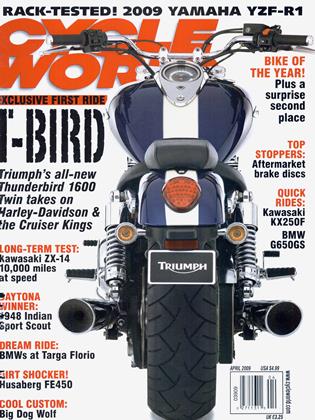

Up FrontBike of the Year

April 2009 By David Edwards -

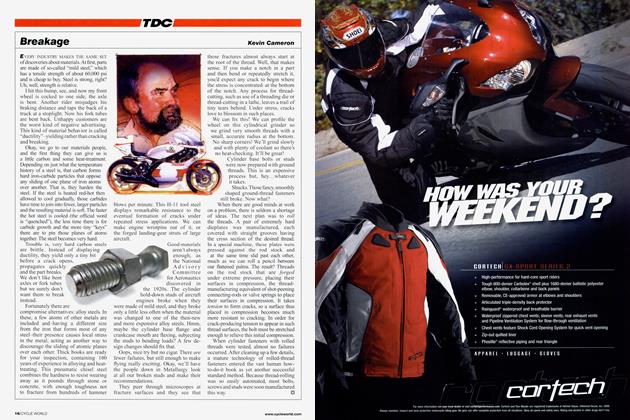

TDC

TDCBreakage

April 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupCall of the Wild

April 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

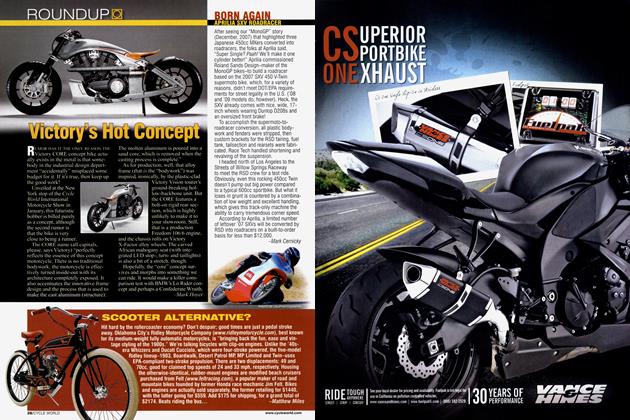

Roundup

RoundupCustoms Live: Reports of Hot-Rodding's Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

April 2009 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupVictiry's Hot Concept

April 2009 By Mark Hover