LEANINGS

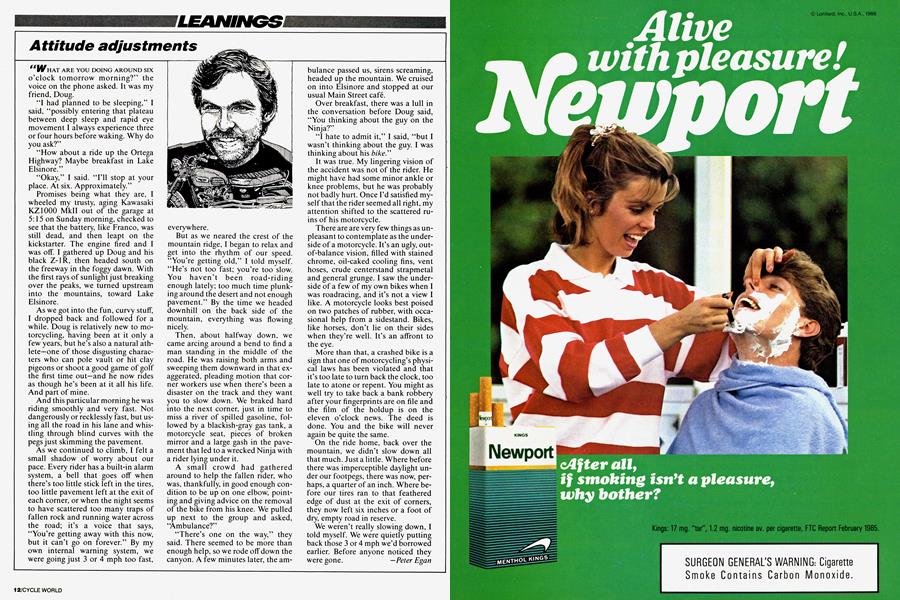

Attitude adjustments

“WHAT ARE YOU DOING AROUND SIX o’clock tomorrow morning?” the voice on the phone asked. It was my friend, Doug.

“I had planned to be sleeping,” I said, “possibly entering that plateau between deep sleep and rapid eye movement I always experience three or four hours before waking. Why do you ask?”

“How about a ride up the Ortega Highway? Maybe breakfast in Lake Elsinore.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll stop at your place. At six. Approximately.”

Promises being what they are, I wheeled my trusty, aging Kawasaki KZ1000 Mkll out of the garage at 5:15 on Sunday morning, checked to see that the battery, like Franco, was still dead, and then leapt on the kickstarter. The engine fired and I was off. I gathered up Doug and his black Z-1R, then headed south on the freeway in the foggy dawn. With the first rays of sunlight just breaking over the peaks, we turned upstream into the mountains, toward Lake Elsinore.

As we got into the fun, curvy stuff, I dropped back and followed for a while. Doug is relatively new to motorcycling, having been at it only a few years, but he’s also a natural athlete-one of those disgusting characters who can pole vault or hit clay pigeons or shoot a good game of golf the first time out—and he now rides as though he’s been at it all his life. And part of mine.

And this particular morning he was riding smoothly and very fast. Not dangerously or recklessly fast, but using all the road in his lane and whistling through blind curves with the pegs just skimming the pavement.

As we continued to climb, I felt a small shadow of worry about our pace. Every rider has a built-in alarm system, a bell that goes off when there’s too little stick left in the tires, too little pavement left at the exit of each corner, or when the night seems to have scattered too many traps of fallen rock and running water across the road; it’s a voice that says, “You’re getting away with this now, but it can’t go on forever.” By my own internal warning system, we were going just 3 or 4 mph too fast, everywhere.

But as we neared the crest of the mountain ridge, I began to relax and get into the rhythm of our speed. “You’re getting old,” I told myself. “He’s not too fast; you’re too slow. You haven’t been road-riding enough lately; too much time plunking around the desert and not enough pavement.” By the time we headed downhill on the back side of the mountain, everything was flowing nicely.

Then, about halfway down, we came arcing around a bend to find a man standing in the middle of the road. He was raising both arms and sweeping them downward in that exaggerated, pleading motion that corner workers use when there’s been a disaster on the track and they want you to slow down. We braked hard into the next corner, just in time to miss a river of spilled gasoline, followed by a blackish-gray gas tank, a motorcycle seat, pieces of broken mirror and a large gash in the pavement that led to a wrecked Ninja with a rider lying under it.

A small crowd had gathered around to help the fallen rider, who was, thankfully, in good enough condition to be up on one elbow, pointing and giving advice on the removal of the bike from his knee. We pulled up next to the group and asked, “Ambulance?”

“There’s one on the way,” they said. There seemed to be more than enough help, so we rode off down the canyon. A few minutes later, the ambulance passed us, sirens screaming, headed up the mountain. We cruised on into Elsinore and stopped at our usual Main Street café.

Over breakfast, there was a lull in the conversation before Doug said, “You thinking about the guy on the Ninja?”

“I hate to admit it,” I said, “but I wasn’t thinking about the guy. I was thinking about his bike.”

It was true. My lingering vision of the accident was not of the rider. He might have had some minor ankle or knee problems, but he was probably not badly hurt. Once I’d satisfied myself that the rider seemed all right, my attention shifted to the scattered ruins of his motorcycle.

There are are very few things as unpleasant to contemplate as the underside of a motorcycle. It’s an ugly, outof-balance vision, filled with stained chrome, oil-caked cooling fins, vent hoses, crude centerstand strapmetal and general grunge. I saw the underside of a few of my own bikes when I was roadracing, and it’s not a view I like. A motorcycle looks best poised on two patches of rubber, with occasional help from a sidestand. Bikes, like horses, don’t lie on their sides when they’re well. It’s an affront to the eye.

More than that, a crashed bike is a sign that one of motorcycling’s physical laws has been violated and that it’s too late to turn back the clock, too late to atone or repent. You might as well try to take back a bank robbery after your fingerprints are on file and the film of the holdup is on the eleven o’clock news. The deed is done. You and the bike will never again be quite the same.

On the ride home, back over the mountain, we didn’t slow down all that much. Just a little. Where before there was imperceptible daylight under our footpegs, there was now, perhaps, a quarter of an inch. Where before our tires ran to that feathered edge of dust at the exit of corners, they now left six inches or a foot of dry, empty road in reserve.

We weren’t really slowing down, I told myself. We were quietly putting back those 3 or 4 mph we’d borrowed earlier. Before anyone noticed they were gone. —Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

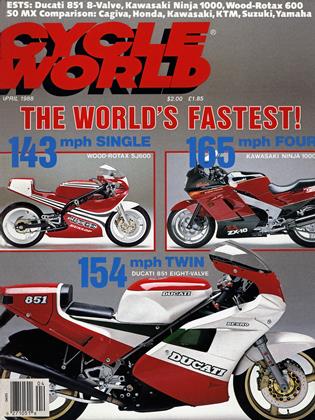

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1988 By Alan Cathcart