Lost summers

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

IT ISN’T EVERY DAY YOU GET A LETTER on cast-off official stationery from the palace of Saddam Hussein, but it happened to me last month.

I have been corresponding, you see, with one SP/4 Darrell Pacheco, who is an MP patrolling the streets of Baghdad. Some of you may recognize the Pacheco name, as Darrell is the brother of Beau Pacheco, editor of our sister publication, Motorcycle Travel & Adventure.

Like Beau, Darrell is an avid life-long motorcyclist, but hasn’t been riding much lately because of his job in Iraq. His story is an interesting one: He’s a 49-year-old veteran of the first Gulf War who stayed in the Army reserves afterward and then retired two years before the 9/11 attack. On 9/12, he did what many of us felt like doing but did not have the means or the strength of will to accomplish-he rejoined the Army and went back to the Middle East.

He’s been there for about nine months now, and isn’t sure when he’s coming home. “Just get me home in time for Daytona,” he writes. “That’ll be one year.”

Despite the constant threats of ambush and land mines and the intense heat (“Woke up from a nap this afternoon and it was 132 degrees...”) his letters are remarkably free from the sort of grousing and complaining in which I, personally, would be tempted to indulge. Still, you can tell, reading between the lines in Darrell’s letters, that he misses his motorcycles back home.

He has a 1978 BMW R80 with R90S fairing and cycle parts on it and a Kawasaki ZRX1100 with the Eddie Lawsonreplica paint scheme, both of which he rides on the Blue Ridge Parkway near his North Carolina home. He’s also owned a Sportster and a VFR750 (“Wrecked it at Deal’s Gap”) and is an avid roadracing fan. He’s hoping to buy a Springer Softail when he gets out, to do some traveling.

Though we aren’t that far apart in age (I’m just six years older), it’s funny how the content of Darrell’s writing reminds me of my own letters from Vietnam in 1969 and 1970. When we can’t ride motorcycles, the dream of doing so fills our plans and sustains us.

My little Army stint in Southeast Asia was the one period of my adult life when I didn’t ride any bikes at all. Although the country was crawling with millions of Honda 50s and Super-90s, we troops had no opportunity to own motorcycles,

and I was never seriously tempted to borrow one from our Vietnamese interpreters because these guys had most of their life savings tied up in their Hondas. They were not toys to the Vietnamese, but their only means of transportation. You didn’t mess around with these bikes.

So in lieu of actually riding, I simply dreamt of riding. I sent away for Triumph and Norton brochures and had them taped on the inside of my foot locker, and I’d spend hours off-duty staring at those pictures and trying to decide which bike to buy when I got out, and where I would go with it. I also sent for brochures from a company in London called Elite Motors Limited, checking into the possibility of foreign delivery of a new Bonneville when I got out. A trip through England on a new Triumph sounded like an ideal way to quickly dispose of 14 months of overseas combat pay. Still does!

Then I hatched a new plan: I would get out of the Army on October 8, 1970, at the Oakland, California, replacement center, buy a new Bonneville or Norton Commando from a San Francisco dealership and ride home to Wisconsin. I wrote my parents and informed them of this scheme.

My dad, who seldom wrote letters, responded almost immediately:

“You will not (underlined three times) buy a motorcycle in San Francisco and ride home in October. Your mother is

worried sick and has hardly slept since you left for Vietnam, and she doesn’t need one more thing to worry about. Have a little mercy. You will get on an airplane and fly home as soon as possible.”

I was 22 years old and free to do what I wanted, but when my dad used this tone, you didn’t cross him unless you wanted to be swatted to death with your own hat. So I gave up on the San Francisco idea and flew home. A few weeks later, it snowed in Wisconsin and I bought a rusty old Volkswagen instead of a bike. Triumphs and Nortons would come later, in better weather.

Still, those bikes in the brochures had done their job, which was boosting morale about the future. I think with my friend Darrell in Iraq, they are serving the same function.

As they are for me, even now.

Last spring, I was diagnosed with Hepatitis C, an unpleasant little virus whose eradication requires six months of injections and pills that make you too queasy and tired to do much but lie on the sofa and stare at the ceiling. (I should really do something about that cobweb and those plaster cracks.) As of this writing, I have five weeks of this delightful treatment left and, though the prognosis is good, the past summer was an almost total write-off for motorcycling. I was simply too tired and dizzy to ride most of the time. I took a few short rides into town, but didn’t have the stamina to go very far.

If you look carefully at the sofa where I spent the summer, however, you will note that it is surrounded by stacks of motorcycle magazines, sales brochures, U.S. road atlases and maps of Europe, England and Mexico. Somewhere in the pile is a book about the Isle of Man...

I may not have ridden much this summer-a few hundred miles total, on the handful of days when I felt okay-but I have lived what is possibly the richest imaginary motorcycle life since my days in Vietnam. Never have I had so many plans.

It’ll be winter when I’m done with this medication, but I’m already plotting a “Payback for the Lost Summer” tour in the Deep South with my new Triumph Bonneville.

I’ll probably hit Daytona this year, too. Maybe finally get to meet SP/4 Darrell Pacheco, who I know only from his letters. With any luck, we’ll both be home by then, back on our bikes. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

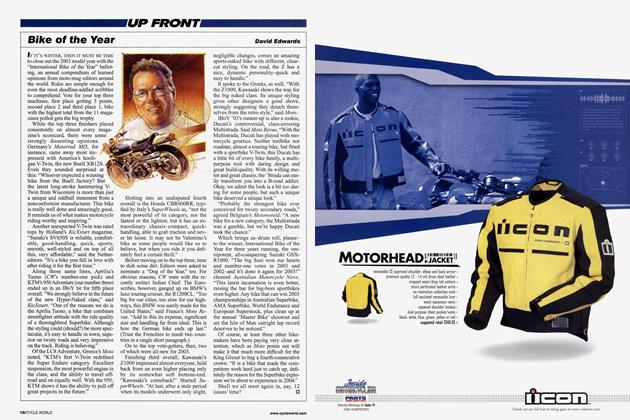

Up FrontBike of the Year

February 2004 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCSuperbike Situations

February 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

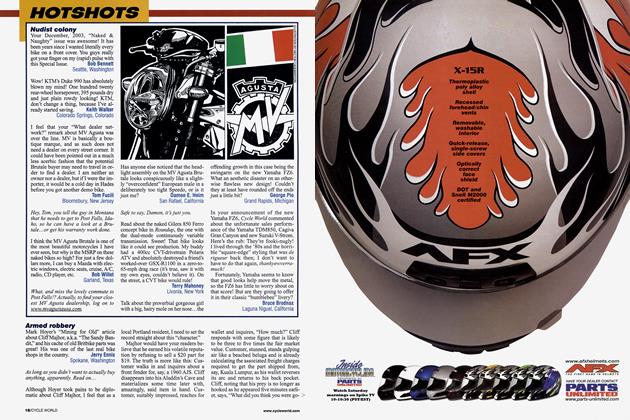

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2004 -

Roundup

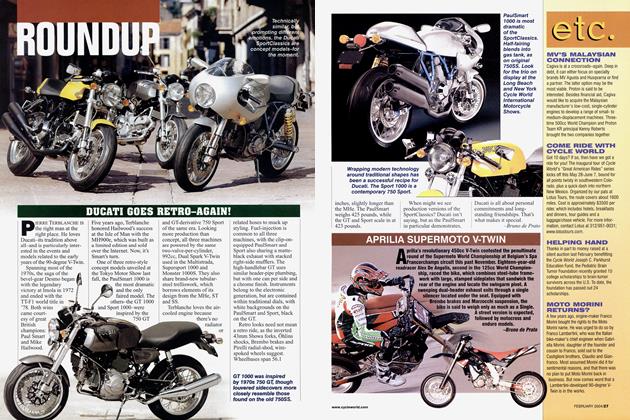

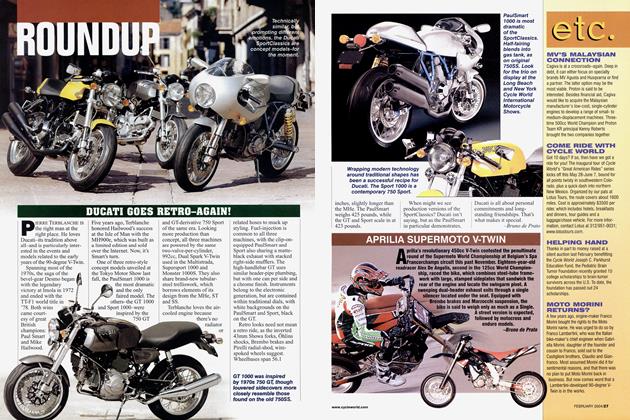

RoundupDucati Goes Retro-Again!

February 2004 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

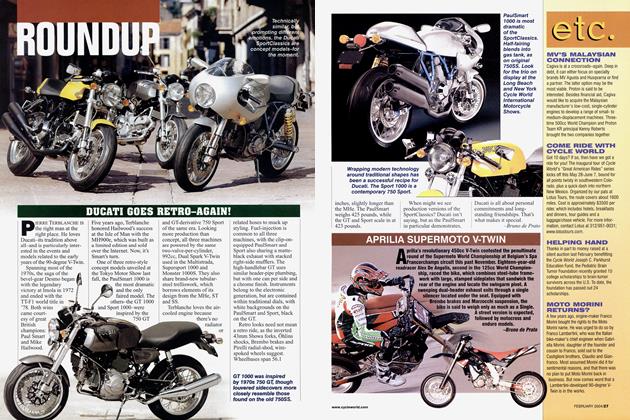

RoundupAprilia Supermoto V-Twin

February 2004 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

February 2004