LEANINGS

Transplants

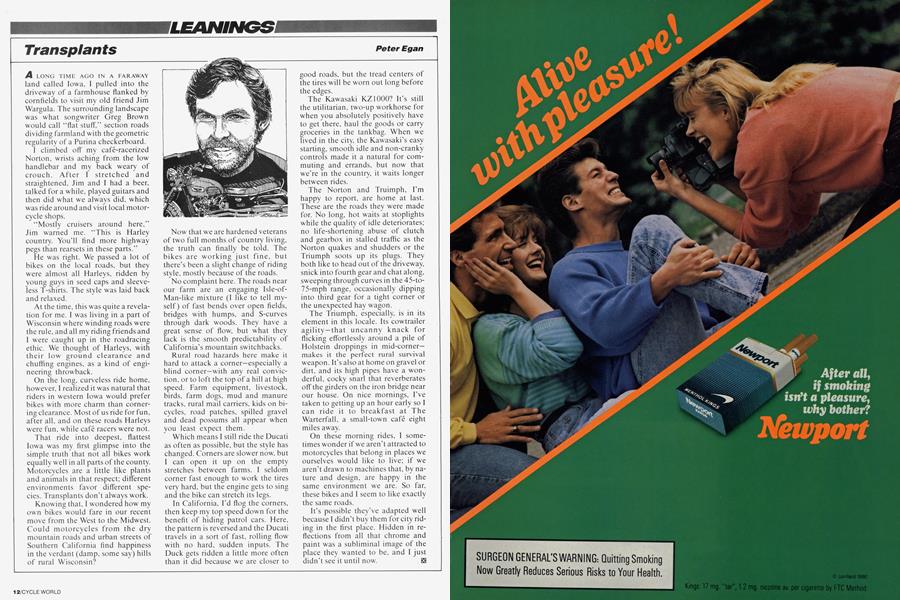

Peter Egan

A LONG TIME AGO IN A FARAWAY land called Iowa, I pulled into the driveway of a farmhouse flanked by cornfields to visit my old friend Jim Wargula. The surrounding landscape was what songwriter Greg Brown would call “flat stuff,” section roads dividing farmland with the geometric regularity of a Purina checkerboard.

I climbed off my café-racerized Norton, wrists aching from the low handlebar and my back weary of crouch. After I stretched and straightened, Jim and I had a beer, talked for a while, played guitars and then did what we always did, which was ride around and visit local motorcycle shops.

“Mostly cruisers around here,” Jim warned me. “This is Harley country. You’ll find more highway pegs than rearsets in these parts.’’

He was right. We passed a lot of bikes on the local roads, but they were almost all Harleys, ridden by young guys in seed caps and sleeveless T-shirts. The style was laid back and relaxed.

At the time, this was quite a revelation for me. I was living in a part of Wisconsin where winding roads were the rule, and all my riding friends and I were caught up in the roadracing ethic. We thought of Harleys, with their low ground clearance and chuffing engines, as a kind of engineering throwback.

On the long, curveless ride home, however, I realized it was natural that riders in western Iowa would prefer bikes with more charm than cornering clearance. Most of us ride for fun, after all, and on these roads Harleys were fun, while café racers were not.

That ride into deepest, flattest Iowa was my first glimpse into the simple truth that not all bikes work equally well in all parts of the county. Motorcycles are a little like plants and animals in that respect; different environments favor different species. Transplants don’t always work.

Knowing that, I wondered how my own bikes would fare in our recent move from the West to the Midwest. Could motorcycles from the dry mountain roads and urban streets of Southern California find happiness in the verdant (damp, some say) hills of rural Wisconsin?

Now that we are hardened veterans of two full months of country living, the truth can finally be told. The bikes are working just fine, but there’s been a slight change of riding style, mostly because of the roads.

No complaint here. The roads near our farm are an engaging Isle-ofMan-like mixture (I like to tell myself) of fast bends over open fields, bridges with humps, and S-curves through dark woods. They have a great sense of flow, but what they lack is the smooth predictability of California’s mountain switchbacks.

Rural road hazards here make it hard to attack a corner—especially a blind corner—with any real conviction, or to loft the top of a hill at high speed. Farm equipment, livestock, birds, farm dogs, mud and manure tracks, rural mail carriers, kids on bicycles, road patches, spilled gravel and dead possums all appear when you least expect them.

Which means I still ride the Ducati as often as possible, but the style has changed. Corners are slower now, but I can open it up on the empty stretches between farms. I seldom corner fast enough to work the tires very hard, but the engine gets to sing and the bike can stretch its legs.

In California, I’d flog the corners, then keep my top speed down for the benefit of hiding patrol cars. Here, the pattern is reversed and the Ducati travels in a sort of fast, rolling flow with no hard, sudden inputs. The Duck gets ridden a little more often than it did because we are closer to good roads, but the tread centers of the tires will be worn out long before the edges.

The Kawasaki KZ1000? It’s still the utilitarian, two-up workhorse for when you absolutely positively have to get there, haul the goods or carry groceries in the tankbag. When we lived in the city, the Kawasaki’s easy starting, smooth idle and non-cranky controls made it a natural for commuting and errands, but now that we’re in the country, it waits longer between rides.

The Norton and Truimph, I’m happy to report, are home at last. These are the roads they were made for. No long, hot waits at stoplights while the quality of idle deteriorates; no life-shortening abuse of clutch and gearbox in stalled traffic as the Norton quakes and shudders or the Triumph soots up its plugs. They both like to head out of the driveway, snick into fourth gear and chat along, sweeping through curves in the 45-to75-mph range, occasionally dipping into third gear for a tight corner or the unexpected hay wagon.

The Triumph, especially, is in its element in this locale. Its cowtrailer agility—that uncanny knack for flicking effortlessly around a pile of Holstein droppings in mid-corner— makes it the perfect rural survival weapon. It’s also at home on gravel or dirt, and its high pipes have a wonderful, cocky snarl that reverberates off the girders on the iron bridge near our house. On nice mornings, I've taken to getting up an hour early so I can ride it to breakfast at The Warterfall, a small-town café eight miles away.

On these morning rides, I sometimes wonder if we aren’t attracted to motorcycles that belong in places we ourselves would like to live; if we aren’t drawn to machines that, by nature and design, are happy in the same environment we are. So far, these bikes and I seem to like exactly the same roads.

It’s possible they've adapted well because I didn’t buy them for city riding in the first place. Hidden in reflections from all that chrome and paint was a subliminal image of the place they wanted to be, and I just didn’t see it until now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1990 -

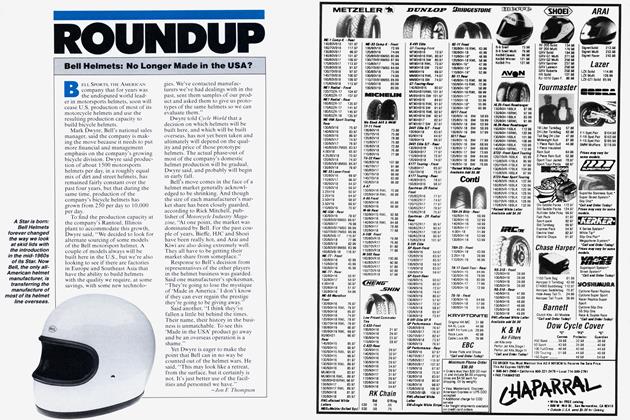

Roundup

RoundupBell Helmets: No Longer Made In the Usa?

October 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: News From Cagiva, Aprilia And Ferrari

October 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

October 1990 By Ron Griewe