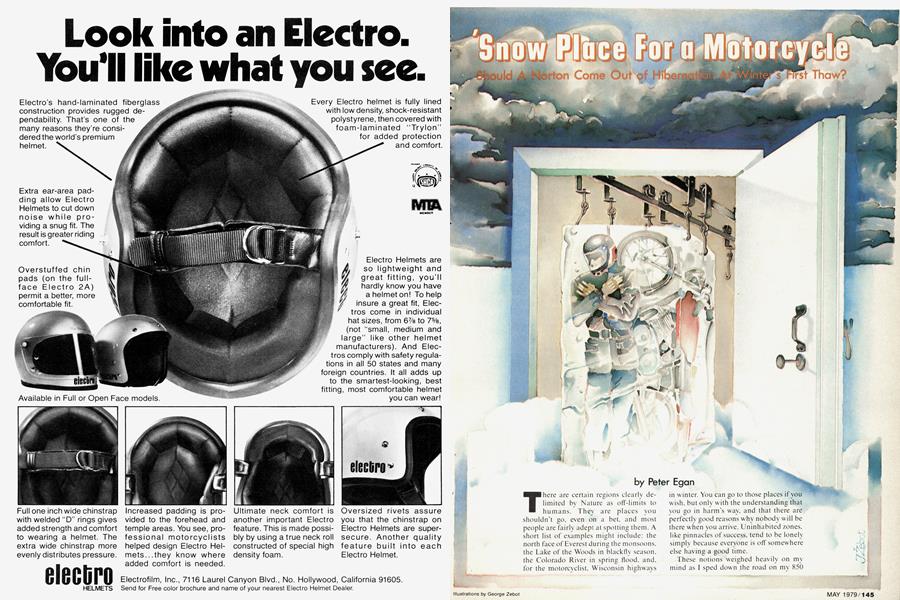

'Snow Place For a Motorcycle

Should A Norton Come Out of Hibernation At Winter's First Thaw?

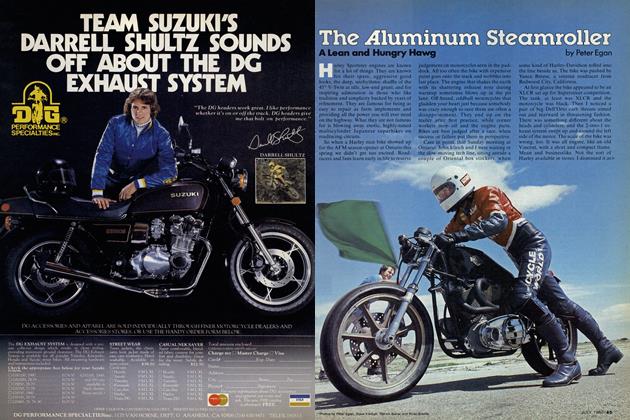

Peter Egan

There are certain regions clearly delimited by Nature as off-limits to humans. They are places you shouldn't go, even on a bet, and most people are fairly adept at spotting them. A short list of examples might include: the north face of Everest during the monsoons. the Lake of the Woods in blackfly season. the Colorado River in spring flood, and, for the -motorcyclist, Wisconsin highways

in winter. You can go to those places if you wish, but only with the understanding that you go in harm’s way, and that there are perfectly good reasons why nobody will be there when you arrive. Uninhabited zones, like pinnacles of success, tend to be lonely simply because everyone is off'somewhere else having a good time.

These notions weighed heavily on my mind as I sped down the road on my 850 Commando, dodging knife-edged drifts on the plowed highway and watching angry snow clouds scud in from the northwest. a solid fast-moving bank of leaden grey and purple. There were no other motorcycles on the road, and very few cars. It was hardly noon and yet the streetlights with their photo-cells sensitive to the growing darkness were switching themselves on in the small towns. In the country, farmyard lights w'ere blinking on. I wasn't sure whether it was the absence of light or of heat which set them glowing. The temperature had dropped about one degree per mile, as though synchronized with my odometer. It was growing dark and cold.

I knew', dumb frozen beast that I was, that as soon as my brain thawed out I would blame Wargula for this whole fiasco. It was Jim Wargula, an old college roommate, who had phoned me at eight o'clock on a Saturday morning in March to see if I wanted to do some country roadracing. Jim lives 100 mi. aw'ay, in Oshkosh— the city with the name that gets laughs in Catskill nightclubs.

“Get up. Egan.'' he said. “It's beautiful outside. I just went out to feed the dogs and discovered that a warm front is upon us. It must be 50°out there. Spring is here! What do you say we blow the cosmoline out of the Nortons."

Jim and I had both bought Norton 850's, his red and mine black, in the last days of the Empire when Norton was trying to recoup some capital by selling Commandos for a song. We had reunions several times a year in which we met at some chosen place and then frightened ourselves all day on twisty back roads, dodging bullchips and farm dogs. Most of these rides took place in the summer, that magical time of year w hen you can see the ground.

Jim waited on the phone w'hile I climbed out of bed and raised a window shade. As soon as I recovered from the sudden searing pain in my eyes, I could see that it was a bright, beautiful morning. The streets were wet with melting snow and there was the sort of vaporous white haze in the air you see only on winter mornings that are unusually warm.

“Okay.” I said. “I'll go for a ride. Where do you w'ant to meet?”

“How about the A & W in Columbus.” Jim suggested. “It's half-way between here and there and it has an indoor restaurant. We can eat lunch and then go for a ride."

I made some coffee and then went downstairs into the dungeon that is our garage and basement to have a look at the Norton. It was in the corner, covered w ith a white sheet, like the furniture of the rich when they have left for the South of France. I bought the sheet, then couldn't afford the vacation. The battery w'as out; the gas tank drained. I'm not prepared on short notice to ride in winter any more. I've had too many close brushes with death-byshivering. As a student I spent most of one winter commuting to class on a Honda CB-160, and that experience taught me a lot of valuable lessons. I learned, for instance, that if you corner a motorcycle with bald tires fast enough on new-fallen snow it is possible to narrowly miss a skidding city bus and knock over three garbage cans filled exclusively with egg shells and grapefruit rinds while sustaining no injury more serious than a sprained thumb and a term paper on Kierkegaard ruined by slush. On a more metaphysical level, I discovered that hot tea is inherently Good, while cold wind represents a sort of Evil.

When I couldn’t stand it any more I sold my 160 and bought a sports car—a 1959 Triumph TR-3 with no side curtains and a hole the size of a cannonball in the otherwise opaque rear window of the convertible top. The Triumph, of course, was no warmer than the Honda, but since it never ran more than three minutes at a time I never had a chance to get really cold. Also, when you tapped the horn button the steering wheel began to smolder and melt, which added a touch of comfort in cold weather. The wiring harness finally burned up and I sold the car for a tremendous profit and bought myself another bike; a 305 Superhawk. By that time it was summer. I was done with winter riding for good.

I took the sheet off the Norton, dumped in a gallon of stale lawnmower gas, strapped its trickle-charged battery back under the seat, and went upstairs to dress. I put on all the clothes I owned and then went down to the garage to get my waxedcotton Belstaff jacket. My wife won’t let me keep it in the regular coat closet because she says it smells like creosote. I wrapped a scarf around my face and buckled my helmet. The Norton's anemic electric starter went “dit,” so 1 started the bike with just enough kicks to steam up my face shield with hot panting breath.

The streets in town were wet, but out on the highway the pavement was dry and clean, bleached bone-white from three months of salting by the county road crews.

I stopped at a gas station to fill my tank. “Beautiful day for a ride,” the attendant said. “I heard we were supposed to get some snow, but it sure doesn’t look like it now.”

I agreed, a little uneasily, and remarked that I’d put on too many layers of clothes and actually felt too warm riding through town—unheard of in early March. 1 pulled out on the highway feeling good about the weather and happy to be back on my bike and going somewhere. The sun shone down on the fields and woods and the birds sang brightly on the telephone wires—or so I imagined, in the whistling isolation of my Star 120.

Then 10 mi. down the road, a small shiver passed over my body. Not an actual, visible shudder, but the kind of shiver that> is more psychic than physical. The sun had gone behind a cloud. I turned and looked over my shoulder. Wrong. The sun had gone behind a lot of clouds. It had disappeared behind a textbook vision of the rolling cold front. A mass of dark winter clouds moved across the sky from the northwest like a giant focal-plane shutter. I shrugged; the air was still nice and warm. About 10 minutes later I plunged into one of those zones of sudden cold that are as vivid to a motorcyclist as a brick wall, or a border on a colored map. From red to blue, faster than you can say “brass monkey.” I felt as though I'd dived into Lake Superior. In 15 minutes the day had gone from benign to angry. I tucked my chin a little tighter into my collar and pressed on.

By the time I’d made the 50 mi. trip to the A & W in Columbus it was dark and cold. The sky was a uniform turbulent nasty grey, and the lights from the restaurant had a warm orange glow. I walked in stiffly, knocking small icicles off my beard, and ordered a very large coffee. The waitress asked cheerfully, “Is that for here or to go?” I was too cold to be kind. I just looked at her and said, “You must be joking.” I took the coffee back to a window table and waited for Wargula.

Motorcyclists in cold weather are always in a quandary over their speed. Should they ride fast and get it over with, enduring the ravages of high-speed wind, or should they ride slowly, prolonging a slightly less terrible agony.

Jim had chosen Slow Death. Coming down the highway his bike looked like one of those lone cavalry horses returning to the fort with a dead rider full of arrows slumped in its saddle, stopping here and there to nibble on sagebrush. I'd never seen Jim ride so slowly, or so stiffly. And I'd never seen a motorcycle turn a corner without leaning, but Jim did it as he pulled into the parking lot. He pulled to a stop and sat on his bike; just sat. not bothering to shut the engine off, as though he expected some kind of emergency ground crew to run out of the restaurant and lift him off his Commando. No help arrived, so he slowly reached for the key and turned it off. A minute later he tilted his head downward and began to look for the kickstand. A stiff robot leg caught the edge of the stand and kicked it out. He swung his other leg over the bike, stood up, looked around to see where he was, and then walked toward the restaurant door with a ponderous I'm-so-cold-now -there's-noneed-to-hurry dignity.

He walked right past my table without looking at me and went to the counter. “Coffee.” he said. The waitress started to ask if that was for here or to go. but something in his voice made her think the better of it. She quickly set out a large w hite styrofoam cup with a plastic lid. Jim paid and walked over to my table. He sat down heavily, without speaking, and peeled the lid from his cup with a hand like a claw. He took a drink and looked darkly into the cup. I feared for a moment that he might dump the stuff over his head, or at least pour it down his boot. But he just warmed his hands over the steaming cup and looked at me, raising one eyebrow in a sudden show' of levity.

“Been here long?” he asked.

“I can’t tell yet.”

Jim looked out the window'. “Lovely weather. It looks like midnight.”

“It’s supposed tc snow.”

Jim nodded. “We better warm up and head for home. I don’t want to spend the winter in this place.” He looked around. “Even if it is warm.”

It took us about two hours to warm up. We’d both quit smoking, but we bought a pack of Lucky Strikes out of the cigarette machine, just for old times, and smoked one after the other. (When you are cold enough, there is something ineffably charming about a glowing cigarette and great clouds of smoke.) Then we had some hamburgers and more coffee. We talked about motorcycles and summer and what it must be like to live in California and then had some more coffee. Snow flurries began to blow against the window. My watch said it was two in the afternoon, but the darkness of the sky made it much later. A light dusting of snow settled into the quilting pattern on our cycle seats and formed a wind-blown vee on the pavement around our tires. It was time to go, so we smoked another half a pack of cigarettes, drank some more coffee, and sloshed out the front door reeling from an overdose of caffeine and nicotine. Jim brushed off the seat, started his cycle with one kick—aided slightly by the electric starter—and closed his face shield. He waited until my bike was running, then held up his hand in a gesture disturbingly similar to a Papal benediction. We put the bikes in gear and split off' at the highway in opposite directions.

All of the cars had their headlights on and left swirling wakes of dry, hard snow that worked its way down the back of my neck and melted. I discovered in a very short time that I'd worn too many layers of clothes in the restaurant; I was a little on the warm and sweaty side. The wind made short work of the heat I'd brought with me. and soon I began to shake. I shook mildly at first with a sort of high-pitched tuning fork resonance, and then more heavily, my uncontrolled shuddering moving down the scale to roughly an open E, played on a bass guitar with a badly-wound fourth string. It went from there to the kind of allout jerking and twitching usually associated with wind-up toy monkeys that hop and play the cymbals at the same time. The rhythm began to feed into my handlebars, sending the bike into those deadly vibrations that warn of an upcoming tankslapper. I slowed down, got a grip on myself, and several miles down the road pulled into a roadside tavern. There I had a plastic cup of an evil brown acidic fluid which the bartender jokingly referred to as “coffee.” I asked if I could have the remains of yesterday's Milwaukee Journal, which lay on the bar, and then retired to the men's room. I stuffed the want-ad and comic sections, respectively, down the pantlegs that covered my left and right thighs; two more pages went up around my calves and tucked into my boots, and the entire front page was spread across my chest, tucked into my belt, and buttoned into my shirt. I emerged from the men's room and crinkled my way stiffly out of the bar, to the momentary distraction of a row of bored farmers who were watching the halftime show of a Texas football gamebroadcast from a mythical land where the grass is green, the sun shines, and the cheerleaders wear neither Belstaff jackets nor, as far as I could tell, newspapers stuffed in their undergarments.

I stepped out into the frozen North, mounted the bike carefully so as not to disturb my armor, and motored down the road. The snow. I noted, had taken a turn for the worse. The flakes grew steadily larger and began to stick to the road instead of blowing across it. My headlight shone into a billowing cloud of w hiteness where the snow came at me in perfectly horizontal flight, parallel to the road, rather than falling from the sky. Headlights loomed in my mirror and a semi roared past and disappeared headlong into i»s ovn swirling snowstorm, leaving me blinded to the exact location of the highway I slowed down to about 35 and then realized that my Norton and 1 would make a line hood ornament for the next Peterbilt

to catch us from the rear. I cranked it back up to 50, fishtailing slightly on the slippery road. On a long sweeping curve the bike began a slow drift to the outside, dangerously close to the berm of snow. I pulled in some opposite lock and stuck my foot out in a clumsy, half-speed parody of Dick Mann at the San Jose Mile. This move

caused me to break out in perhaps the world’s coldest sweat, so 1 slowed down again.

When the road straightened out I began to grin, as best I could, inside my scarf and helmet. It was the same self-deprecating grin I might use if I discovered that a con artist had tricked me out of my life’s savings and stolen my car, taking my wife along as a willing hostage. Tricked again. Had. Lured from my snug house by the shabby promise of a warm day in winter; the flip side of a cold day in hell. I must have been crazy. I’d broken all my own rules; I'd gone to a place where I don't belong.

Going where you don’t belong, I decided a long time ago, is the root of all misery and the soul of all adventure. For instance, if you jump out of an airplane and find that your parachute doesn’t open, you realize very quickly that your problem is much more basic than a malfunctioning silk canopy; the real problem is that you are 5000 feet off the ground and falling through space. That is, you are in a place where you don’t belong. Or if you are a Formula One driver and you hit some oil in a very high-speed curve, say in the Karussel at Nurburgring. the problem is not so much that you've hit oil; the problem is that you are in a very fragile machine going 120 miles per hour. You are— you guessed it—in a Place Where You Don't Belong. If you hadn't gone there you'd be home now. Everything would be all right. There are hundreds of other places where people don’t belong: mountainsides in the Himalayas, foxholes in foreign countries, 13-foot sailboats in the mid-Atlantic, bars full of drunks, spying in the Kremlin, whorehouses. New York, milking rattlesnakes, hang-gliding off El Capitan, shrieking down Bray Hill on an OW-1, dodging bulls in Pamplona, consorting with minors, and so on. All wonderful adventures, but fraught with some degree of peril because you really shouldn’t be there. You are more or less asking for it. And if you get it, not much sympathy will be forthcoming. You’ve gone by your own device to a place without mercy. Sometimes a motorcycle is a place where you don’t belong. Like in the w inter, when the first good blizzard of the year blows out of the northwest and clogs the road with drifts of blinding snow'. Sometimes you find yourself in a place where you don’t belong not because you are adventurous, but because you haven’t got the sense God gave a chipmunk. Because you are, in the words of my third-grade teacher, a silly goose. And. yes, because you are dumb as a stump.

A four-wheel drive Bronco sped easily past me. Two children in the back watched me wide-eyed and then waved. I waved back by cautiously lifting a couple of fingers from the grips. The children suddenly turned aw7ay and made animated gestures of conversation w ith their father, who was driving. I couldn’t hear the conversation, but I knew what they were saying. (Daddy, what does “cretin” mean?)

The road was ridiculous. A solid layer of snow now' blanketed the pavement, except where the strongest wind swept across it. Drifts were forming at a diagonal to the centerline. My front tire began to turn more slowly than the rear; it was only a matter of time until the front fender jammed with ice and snow and set technology back ten thousand years by turning my wheel into a skid—or a runner. A restaurant billboard told me that I was still five miles from town, and I suddenly had to ask myself, “Is it possible to go any farther?” “No,” said a voice that I barely recognized as my own, but was nevertheless glad to hear. “Dump this two-wheeled deathtrap somewhere and thumb it home.”

Just then, like a mirage in a frozen Sahara, there appeared a lighted building on the roadside. It was a turquoise steel building in the middle of nowhere (i.e.. just west of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin) with big display windows across the front and a giant yellow Yamaha sign shining like a star in the east out of the snowy darkness. “Thank God for tin buildings and giant international corporations,” I mumbled to myself, punching my left turn signal switch with a remote, frozen appendage I recognized as my left thumb.

When I walked inside two men and a boy in flourescent orange deer-hunting hats and open galoshes were trying to trade in a purple snowmobile with a leopardskin seat, bargaining with a salesman in a camouflaged duck-hunting hat and open galoshes. Each of the four had one foot on the snowmobile in question. The salesman smiled and said, “Hell of a day for bikes! We're supposed to get fifteen inches tonight. I suppose you come in here to buy a set of chains for that thing!”

“Snow tires, probly,” one of the men said and we all had a good laugh. Then I asked if they had winter storage space for motorcycles.

“You bet. Five bucks a month. Pay w hen you pick it up. Bring it around back.”

I pushed the Norton around to the rear of the building while the salesman opened an electric overhead garage door. It was a dark, cold warehouse-style room with maybe 100 bikes jammed in tank-to-tank. A winter tomb for the two-wheeled undead; consecrated earth in a Dracula’s castle of slumbering bikes who only come out when it’s warm. The salesman looked over the sea of mirrors and handlebars and finally found an open space. I shut off the fuel, wiped the bike down with a rag, and eased the Norton into a slot between a Honda 305 Dream with a duct-tape seat and a full-dress Yamaha 200 Electric Start with ape-hangers and a backrest that somehow reminded me of the monogrammed aluminum screen door on my neighbor’s house. The Norton looked lost in the vast stygian chaos of bikes, and I felt a tinge of regret when the lights went out and the garage door came down; it was like leaving my dog at the kennels. But blizzards were Nature’s way of telling you to park your bike.

I told the salesman I’d be back on the first warm day of spring, then trudged out to the highway to hitch a ride. It was snow ing harder and the flakes were coming down the size of small paper plates. The wind was really blowing now7. The headlights of passing cars were nothing but soft globes of whiteness in the swirling snow. The third car to pass suddenly locked up his tires and stopped just down the road. I ran up and got in. A young man was driving. He had hangers in the back window and looked like a college student.

“Terrible time to be out hitch-hiking,” he said. “How did you ever end up way out here?”

“I rode my motorcycle.” I said.

The smile froze on his face and he cast a sidelong glance at my clothes and the helmet in my lap. He laughed, a little uneasily. It was the same reaction you get if you tell people you’ve just arrived from the planet Mongo. With a more subdued and cautious voice he asked, “Where are you headed?”

“Home,” I said, savoring the word and thinking about a steaming hot shower, “where I belong.”