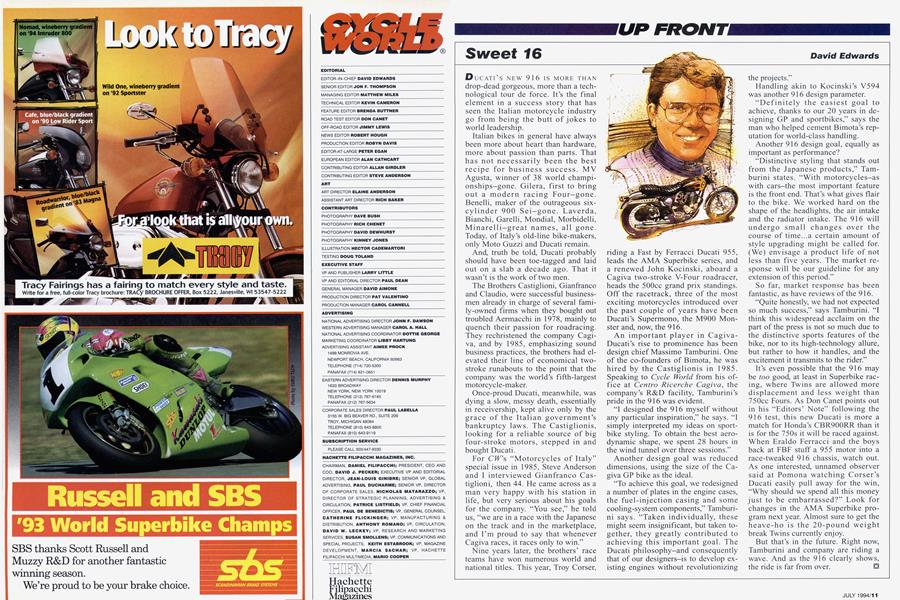

UP FRONT

Sweet 16

David Edwards

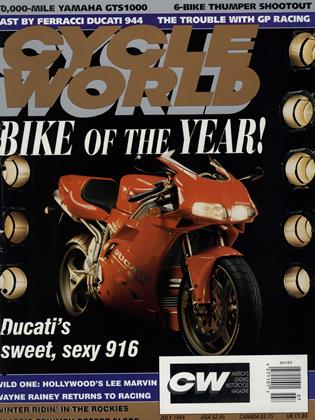

DUCATI’S NEW 916 IS MORE THAN drop-dead gorgeous, more than a technological tour de force. It’s the final element in a success story that has seen the Italian motorcycle industry go from being the butt of jokes to world leadership.

Italian bikes in general have always been more about heart than hardware, more about passion than parts. That has not necessarily been the best recipe for business success. MV Agusta, winner of 38 world championships-gone. Gilera, first to bring out a modern racing Four-gone. Benelli, maker of the outrageous sixcylinder 900 Sei-gone. Laverda, Bianchi, Garelli, Mondial, Morbidelli, Minarelli-great names, all gone. Today, of Italy’s old-line bike-makers, only Moto Guzzi and Ducati remain.

And, truth be told, Ducati probably should have been toe-tagged and laid out on a slab a decade ago. That it wasn’t is the work of two men.

The Brothers Castiglioni, Gianfranco and Claudio, were successful businessmen already in charge of several family-owned firms when they bought out troubled Aermacchi in 1978, mainly to quench their passion for roadracing. They rechristened the company Cagiva, and by 1985, emphasizing sound business practices, the brothers had elevated their line of economical twostroke runabouts to the point that the company was the world’s fifth-largest motorcycle-maker.

Once-proud Ducati, meanwhile, was dying a slow, messy death, essentially in receivership, kept alive only by the grace of the Italian government’s bankruptcy laws. The Castiglionis, looking for a reliable source of big four-stroke motors, stepped in and bought Ducati.

For CW's “Motorcycles of Italy” special issue in 1985, Steve Anderson and I interviewed Gianfranco Castiglioni, then 44. He came across as a man very happy with his station in life, but very serious about his goals for the company. “You see,” he told us, “we are in a race with the Japanese on the track and in the marketplace, and I’m proud to say that whenever Cagiva races, it races only to win.”

Nine years later, the brothers’ race teams have won numerous world and national titles. This year, Troy Corser, riding a Fast by Ferracci Ducati 955, leads the AMA Superbike series, and a renewed John Kocinski, aboard a Cagiva two-stroke V-Four roadracer, heads the 500cc grand prix standings. Off the racetrack, three of the most exciting motorcycles introduced over the past couple of years have been Ducati’s Supermono, the M900 Monster and, now, the 916.

An important player in CagivaDucati’s rise to prominence has been design chief Massimo Tamburini. One of the co-founders of Bimota, he was hired by the Castiglionis in 1985. Speaking to Cycle World from his office at Centro Ricerche Cagiva, the company’s R&D facility, Tamburini’s pride in the 916 was evident.

“I designed the 916 myself without any particular inspiration,” he says. “I simply interpreted my ideas on sportbike styling. To obtain the best aerodynamic shape, we spent 28 hours in the wind tunnel over three sessions.”

Another design goal was reduced dimensions, using the size of the Cagiva GP bike as the ideal.

“To achieve this goal, we redesigned a number of plates in the engine cases, the fuel-injection casing and some cooling-system components,” Tamburini says. “Taken individually, these might seem insignificant, but taken together, they greatly contributed to achieving this important goal. The Ducati philosophy-and consequently that of our designers-is to develop existing engines without revolutionizing the projects.”

Handling akin to Kocinski’s V594 was another 916 design parameter.

“Definitely the easiest goal to achieve, thanks to our 20 years in designing GP and sportbikes,” says the man who helped cement Bimota’s reputation for world-class handling.

Another 916 design goal, equally as important as performance?

“Distinctive styling that stands out from the Japanese products,” Tamburini states. “With motorcycles-as with cars-the most important feature is the front end. That’s what gives flair to the bike. We worked hard on the shape of the headlights, the air intake and the radiator intake. The 916 will undergo small changes over the course of time...a certain amount of style upgrading might be called for. (We) envisage a product life of not less than five years. The market response will be our guideline for any extension of this period.”

So far, market response has been fantastic, as have reviews of the 916.

“Quite honestly, we had not expected so much success,” says Tamburini. “I think this widespread acclaim on the part of the press is not so much due to the distinctive sports features of the bike, nor to its high-technology allure, but rather to how it handles, and the excitement it transmits to the rider.”

It’s even possible that the 916 may be too good, at least in Superbike racing, where Twins are allowed more displacement and less weight than 750cc Fours. As Don Canet points out in his “Editors’ Note” following the 916 test, this new Ducati is more a match for Honda’s CBR900RR than it is for the 750s it will be raced against. When Eraldo Ferracci and the boys back at FBF stuff a 955 motor into a race-tweaked 916 chassis, watch out. As one interested, unnamed observer said at Pomona watching Corser’s Ducati easily pull away for the win, “Why should we spend all this money just to be embarrassed?” Look for changes in the AMA Superbike program next year. Almost sure to get the heave-ho is the 20-pound weight break Twins currently enjoy.

But that’s in the future. Right now, Tamburini and company are riding a wave. And as the 916 clearly shows, the ride is far from over. □