The buck-a-day, 25-year habit

LEARNINGS

"WHAT HAVE YOU GOT THERE?” MY wife Barbara asked as I walked in the front door. I was carrying a small rectangular box, holding it slightly away from my body, the way you hold a dead skunk or a small dog who’s just been swimming in the pond behind the toxic waste dump.

“A new battery for the Kawasaki,” I said. “I just wrote a check for it.”

Barb, who adds and subtracts with a little more accuracy than I do (I hope), took the checkbook out of her purse. “How much was it?”

“Thirty-four dollars and nine cents.”

A sigh issued forth. Not an annoyed sigh, but one of those lifegoes-on types. Barb recorded the amount in the back of the book and said, “I wonder how much we’ve spent on motorcycles over the years?” She gazed wistfully at the checkbook for a moment and said, “Maybe it’s better we don’t know.”

I went out to the garage to install the battery in the KZ 1000, which certainly deserved it. The bike is a 1980 Mkll model that I had been kickstarting for two years on a dead battery. I can’t think what possessed me to buy a new battery; perhaps the novelty of using the starter button again, or a suspicion that the starter motor might be rusted solid.

As I dropped the new battery heavily into its cradle, I began to think about what Barb had said. How much had we (okay, mostly I) spent on motorcycles over the years? It was a fair question, I suppose.

I’d bought and sold quite a few bikes since that first ratty James-Villiers in 1963. Mostly cheap, used ones, with only a few expensive new bikes in the mix. Some I’d restored lavishly (Armor-All, fresh chain lube, the whole bit), yet others had required no more than an oil change or a clutch cable during my entire stewardship. I’d hardly ever made money on a motorcycle, but it seemed to me that I hadn’t ever lost much on a bike, either.

I’d always avoided adding up the true cost of my obsessions, partly out of guilt, no doubt, but partly because I cling to the ancient philosophy that investments and enthusiasm are two different things. Like fire and water.

I prefer a universe where the only significant bottom-line is death, and your travel expenses en route don’t matter much. Or something.

Nevertheless, I began to think that after a quarter of a century of motorcycling, it might be time for an accounting of sorts. Had my years of motorcycle ownership been merely a fun, affordable hobby? Or was it a passion whose excesses had permanently stunted Barb’s and my economic growth, preventing us from owning the oil wells, the steamship companies and the industrial empire we so richly deserved? If I had invested that $ 1800 in blue chip stocks back in 1975 rather than in a Norton, would we now be skiing in Switzerland with Malcolm Forbes rather than eating at Flo’s Airport Cafe with people like Steve Kimball? Perhaps if I hadn’t bought the RD350 eight years ago, we could now afford a Chevy van without noisy lifters, or even have the cat fixed.

That evening, after installing the battery, I went in the house, got myself a pencil and a yellow legal pad and began to compute.

I made four columns across the page with the following heads: Bike; Price Paid; Repair/Restoration Cost; and Price Sold For. After adding, subtracting, dividing and figuring averages to the best of my ability, I came up with some possibly fascinating statistics, depending upon how easily you are fascinated.

First, it turns out I’ve owned 21 motorcycles, with a price range from $50 for the cheapest to $3700 for the

most expensive. When I added them up, the total cost of all these bikes was $ 19,055, for an average purchase price of $907.38.

Okay, next column. The total repair/restoration costs came to a mere $2000, which must be wrong because it sounds too cheap, but I haven’t been able to invent or recall any other hidden costs. Most of the work I’ve done on bikes has been laborintensive—sanding, painting, installing pistons, fork seals, etc.—but the actual parts costs have been remarkably low. Add those costs to the purchase prices, and suddenly my total for all motorcycles is up to $21,055, with an average total cost for each bike being $ 1002.62.

A thousand dollars a bike.

Now, then. I added up the selling prices of all the bikes I’ve sold, plus the current market value of the four I still own (estimated toward the low side—what I could get for them if they had to be sold tomorrow), and got a value of $ 16,465, or an average selling price of $784.05.

That means my total losses over 25 years and 21 bikes have been $4590, or $218.57 per bike.

Dividing that $4590 by 25,1 get an annual cost of $183.60, or $3.53 a week.

That’s about fifty cents a day.

The alert reader will notice I have not included the cost of insurance, sales tax or registration. That’s because these fees have varied widely depending on where I was living and the type of insurance carried (liability with or without collision/theft, etc.). But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that these expenses actually double the cost of motorcycling, which they can easily do.

That would drive the cost all the way up to a dollar a day.

After arriving at this astounding conclusion, I was going to suggest that most of us could afford to ride motorcycles simply by giving up some small daily pleasure—a good cigar, a drink in the evening, a movie or whatever—but I couldn’t think of a single worthwhile vice that still costs only a dollar a day.

So, you’re on your own. If you can find a cheaper way to throw money around, jump on it. Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAdios, Specialization

December 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeEngineers

December 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupWhither the Passenger?

December 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

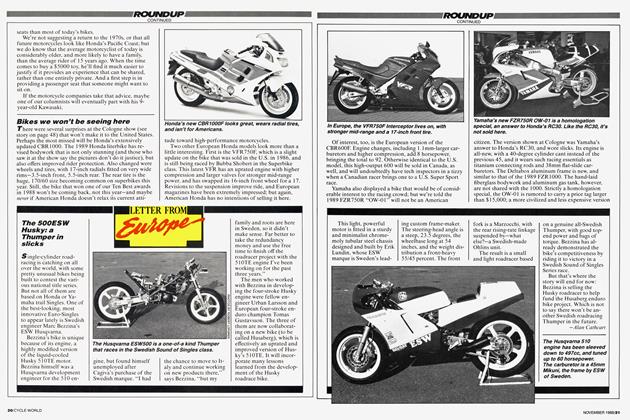

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

December 1988 By Steve Anderson