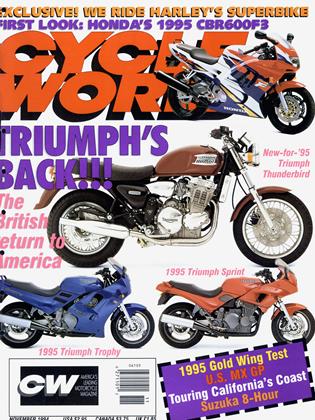

SHOOTING THE COAST AGAIN

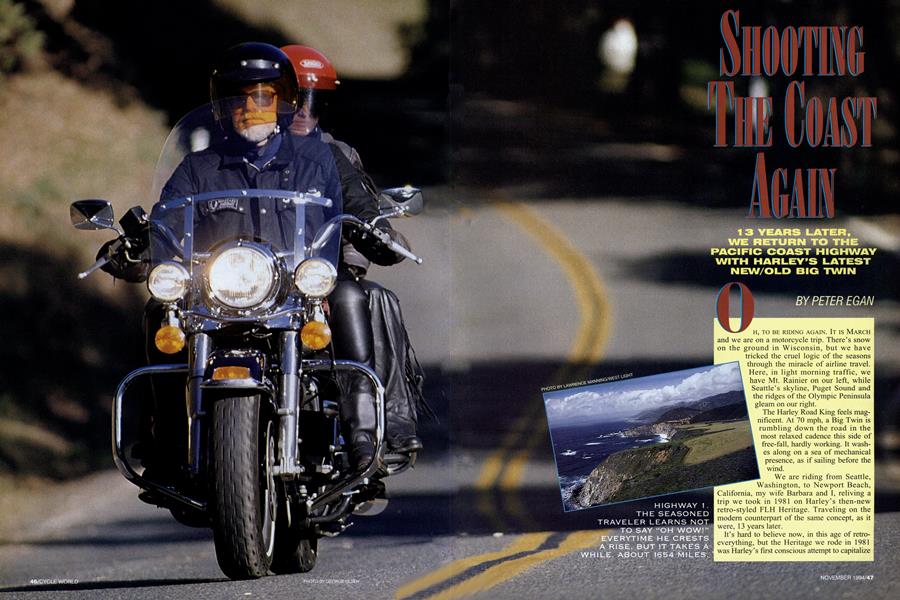

13 YEARS LATER, WE RETURN TO THE PACIFIC COAST HIGHWAY WITH HARLEY'S LATEST NEW/OLD BIG TWIN

PETER EGAN

OH, TO BE RIDING AGAIN. IT IS MARCH and we are on a motorcycle trip. There’s snow on the ground in Wisconsin, but we have tricked the cruel logic of the seasons through the miracle of airline travel. Here, in light morning traffic, we have Mt. Rainier on our left, while Seattle’s skyline, Puget Sound and the ridges of the Olympic Peninsula gleam on our right.

The Harley Road King feels magnificent. At 70 mph, a Big Twin is rumbling down the road in the most relaxed cadence this side of free-fall, hardly working. It washes along on a sea of mechanical presence, as if sailing before the wind.

We are riding from Seattle, Washington, to Newport Beach, California, my wife Barbara and I, reliving a trip we took in 1981 on Harley’s then-new retro-styled FLH Heritage. Traveling on the modem counterpart of the same concept, as it were, 13 years later.

It’s hard to believe now, in this age of retroeverything, but the Heritage we rode in 1981 was Harley’s first conscious attempt to capitalize on its own rich history—to style a bike that looked old and classical rather than incrementally more modem.

Underneath, the bike was a basic 80-inch Shovelhead Electra-Glide styled to evoke the past. It had fringed leather saddlebags with conchos and streamers, a big sprung buddy seat, simple windshield (no fairing) and two-tone green and orange paint in muted, antique tones.

The new Road King follows a similar path. It’s little more than a restyled version of last year’s FLH Sport (one of which I bought brand-new in 1992), with fewer Seventies Moderne styling touches-such as the old plastic instrument pod and the puffy seat. The new one has a speedo on the tank, a cleaned-up front end and a restyled seat.

Better looking, I think. But will it be as practical and comfortable on the road? How

does it stack up against the Heritage we rode 13 years ago?

We have about 1500 miles of coastline in which to find out.

e have already learned a few things that morning, starting from the moment News Editor Robert Hough (who rode the bike from the CW office to Seattle in three Interstate-pounding days) handed us the keys in the hotel parking lot.

Saddlebags on the Road King are roomier than before because the battery has been moved under the seat, and the lids are now hinged. The small, stock luggage rack has been eliminated, however, so our duffel bag of rain gear has to be bungeed directly onto the painted (now scuffed) rear fender. Two-up tourers will need to order the optional luggage rack/backrest.

Handlebars are wider and lower, requiring a slight forward lean rather than the classic Electra-Glide ramrod posture. The seat is comfortable, but firmer at first sitting. Otherwise the bike feels and sounds exactly like the FLHS. Instant start on choke (ta-tuff ta-tuff ta-tuff), quick warm-up, rolling. Out of the hotel parking lot, onto the highway.

As Seattle disappears behind us, tapering

to wooded countryside, we swing toward the coast. In Westport we are forced to pull over for a sign that says Brady’s Oysters. Looking out at the bay, we eat $5 worth of excellent smoked oysters and soak up the sun.

I ask Barb how the passenger seat is and she says, “Perfect.”

A ringing testimonial. Come to think of it, the front seat is slightly better than my old one, which was very good. Handlebars? As the day wears on, they are more comfortable than the old ones. That slight forward lean allows the spine to stretch and flex when needed, rather than compress and topple.

The other key comfort item on the Road King is the windshield. It works just like the old one-which is to say very well-but has fortunately lost the sliding adjustment panel that used to do little more than trap ugly insects. Not much leg or knee protection, but the upper body sits in a nearly calm pocket of air.

After 150 miles of riding, we are finally on the ocean, and one of the most jaw-droppingly beautiful coastlines in the world. In a few short hours we cross out of Washington, across an amazing arc of high bridge over the Columbia River into Astoria, Oregon.

It’s a spring-break weekend, and virtually everyone in the Northwest is at the beach. Resort towns are packed with crawling traffic, but Highway 101 opens up into great swooping stretches of beach with sea spray and wind-blown sand raking across the road, all punctuated by quiet river inlets, deep forest and driftwoodstrewn marshes. It’s a coastline where the grandeur of Nature still dwarfs all human enterprise.

Just as on our first trip, we ride through lively beach towns, such as Manzanita and Rockaway Beach and find ourselves tricked into staying the night at landlocked Tillamook because it’s too late to continue; darkness descends, restaurant exhaust fans beckon.

n Sunday we rejoin the coast, but then strike farther inland toward McMinnville to visit Barb’s old friend Maureen Spurgeon. The road over the coastal range, Route 22, is a sinuous road of sportbike dreams through the forest, with alternating glens of sun and warmth, cool shade and frosty road. If I lived on this road, I would have a CBR600F2, some good leathers and a part-time job.

We have breakfast with Maureen, who tells us the population of McMinnville has doubled in four years, with California earthquakes increasing the rate of immigration. After breakfast, we take Highway 18 back to the coast at Lincoln City and it, too, seems to have doubled in population.

Lots of traffic. We can see growth in nearly eveiy town on this route.

As my friend Chris says, the world is filling up.

In the with these Harley its semi-urban is effortless easy to midrange settings ride, torque. But it is out of town, on the somewhat busy, curving coastal roads that the Road King disappoints. You move out to pass, twist the grip, realize you can’t quite make the pass, then move back into line.

The horsepower isn’t there and the window of opportunity is too small.

You are also precluded from making the classic downhill sportbike pass into a corner because you may run out of cornering clearance. The Road King leans far better than the old 1981 Heritage, which clanged the pavement everywhere, but it still resists being stuffed into comers. It can be ridden briskly, but aggressive moves are out. The bike encourages a stately riding style.

Just south of Coos Bay, tendrils of lateafternoon fog begin snaking up over the roadway from the cliffs below, as if blown by theatrical smoke machines. Suddenly it’s cold, the mist supercooling our hands, knees and feet with evaporative streams of water. Just about the time I get cold enough to preserve my body for a cryogenic wake-up call in the 22nd century, we roll into Gold Beach and see a sign glowing weakly in the blinding whiteness. It says “Ireland’s Rustic Cabins, With Fireplaces.”

The skid marks may still be found on the road. Ten minutes later we are sitting in a snug log cabin with a roaring fire. Anything you want, we got it right here in the USA.

We awake the next day to cool, moody weather, but the fog is burning off into another perfect day.

Oregon’s coast ends at Brookings. Welcome to California.

Whenever I cross a state line, I try to watch the landscape for natural changes that might have caused folks to draw that otherwise arbitrary line on the map. Offhand, I couldn’t remember what separated Oregon from California until we got there. Now it hits me:

Redwoods.

How could I forget. We cruise through the towering majesty of Redwood State Park (individual rays of sunlight piercing the cool cathedral silence) and I gradually realize why I had forgotten. The redwood forests are beautiful beyond our capacity to remember. There is no way for the poor, limited human mind (mine, anyway) to store an accurate image of those huge, mysterious, planet-darkening redwoods.

Ronald Reagan thought we could leave just a strip of these trees along the road for motorists to enjoy, and lumber out the rest. Teddy Roosevelt spun in his grave. T.R. camped in these woods for three days under the stars. (Think of it: a President who camps.) And next time we will, too.

On the road south we begin to see another almost-forgotten sight: backpackers and hitch-hikers with that peculiar, blissful thousand-yard stare you see only on Highway 1. This coastline, like too much absinthe, will do it to you. The scenery should be a controlled substance.

We detour through the amazing Avenue of the Giants, then swing back down through Ft. Bragg and into the restored port town of Mendocino for the night.

he next day we ramble down the coast in light rain, then turn inland along the Russian River, past Jack London’s Wolf House in Glen Ellen, and over the Oakville grade into Napa Valley. There we visit our old motorcycling friends Gil Nickel and Beth Yorman, who own the Far Niente winery.

Far Niente comes from the Italian, Dolce far niente, which means “It is sweet to do nothing.”

Indeed it is. Gil and Beth are originally from Oklahoma, where hospitality is raised to an art form that we northerners have only read about in books. For two days, they ply us with great food and fine wines and show us around.

When it’s time to leave, Gil climbs aboard his brand-new red BMW R1100RS and accompanies us south for the first 50 miles toward San Francisco. The BMW-which I normally think of as a reasonably big bike-suddenly looks small and nimble. Everything’s relative.

Traffic gradually gains density and suddenly we come over a rise and there is the Golden Gate Bridge. If there’s something better than hearing two large cylinders resonate across the Golden Gate on a warm, sunny, fog-free day, please drop me a post card and let me know what it is. (Nothing perverse, please.)

On the city side, we turn left and head over to the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco, famed beatnik Mecca of past times

and home of Caffe Trieste, whose walls have resonated to the words of Ginsberg,

Ferlinghetti, Kerouac &

Co. We have an espresso, as we did 13 years ago, and it still proves second only to loud explosions as a stimulant.

uitably hopped up, we get back on the road and jitter south through Half Moon Bay and then along the sublime Skyline Boulevard for lunch at the famous

motorcyclist’s water hole, Alice’s Restaurant. A mid-week smattering of Harleys, a few older Japanese bikes; nothing trendy here, just well-worn, hard-ridden bikes. I steer us back to the coast on that other great Bay Area road, Highway 84 down to San Gregorio Beach and Highway 1.

Santa Cruz...the Army rifle ranges of Ft. Ord...Monterey...and suddenly we find ourselves in late-aftemoon golden sunlight on the famous cliff-side roads of Big Sur.

This is a road where the rugged beauty of the coast competes for your attention with 300-foot dropoffs. You grind the floorboards hard and suddenly envision what a large splash a Road King would make in the surf below. You feel like Icarus on a hot day. It concentrates the attention.

By sunset, my capacity to absorb beauty is exhausted and my attention span is frazzled, so we stop at the Inn at Ragged Point. We open our floor-length room curtains to an ocean view that looks like a huge painting of a ocean view, only with fewer mistakes and more raccoons.

The raccoons are looking in—five of them—to see if we have any food. They end up with about half of our takeout dinner from the drive-in next door. Now I’ve seen everything.

ast day: a swing past the Hearst Castle, inland through the green hills around San Luis Obispo. We stop for gas in Los Alamos and a big guy comes across the street to admire the Road King. “Gotta get one,” he says. His T-shirt reads, “Harley-Davidson: They gotta go backwards to go forward.”

It’s Good Friday as we crawl through congestion in Santa Barbara and down the coast to Malibu, where the work of last year’s fires is still in evidence on the hills

above the recent mud slides that streak the Coast Highway.

It’s not long before we make it to the Cycle World office on a dark misty afternoon. Again. Thirteen years later. Changes?

The bike is much better. The old Heritage had charm, but serious vibration was part of the package. It fatiguecracked its crash bar, shook the springs and rubbers off its footrests. The engine often pinged under load and the

transmission shifted with the loud finality of a prison-gate deadbolt. It had charisma, but it could be cranky and difficult.

The new Road King handles better, stays together, runs smoother, shifts better and is altogether more comfortable and satisfying to ride, yet it maintains that same Harley/Other Bike distance from the rest of the motorcycle world that the Heritage had in 1981.

A big Harley is unique, and on the road it never lets you forget what it is, never stops entertaining with its colorful personality. There are moments when you wish for more horsepower, but there are no dull moments on the Road King, regardless of road conditions. And in five days and 1654 miles of travel, it felt good to fire it up and roll every morning.

The state of the Coast?

Still beautiful, still waiting, still bigger than all of us.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIncident On the Angeles Crest

November 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGs-Ing It

November 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCEngine Architecture

November 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Reveals Trick 250

November 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Gets Savage For 1995

November 1994