precious Resources

In MotoGP, winning now comes down to the serious business of fuel and tires

NEIL SPALDING

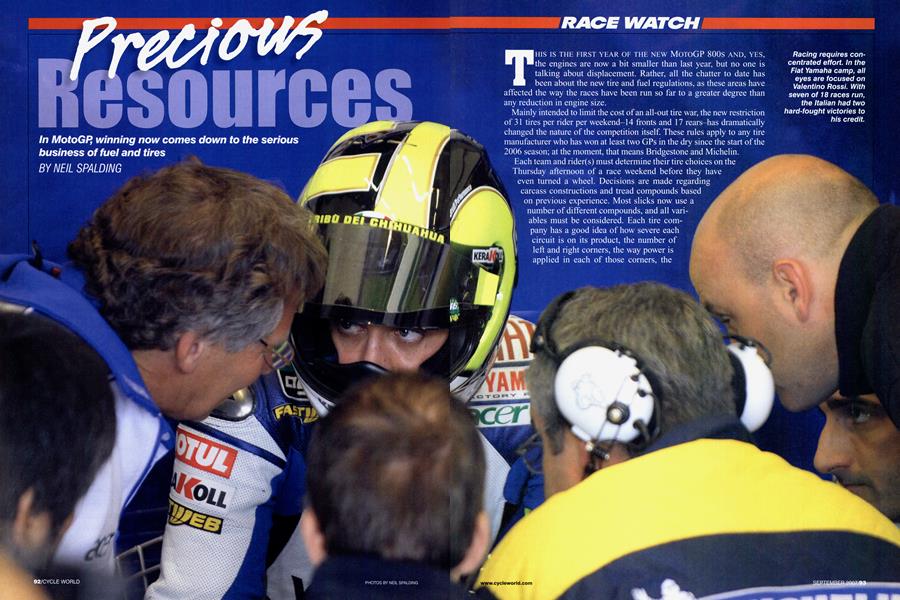

RACE WATCH

THIS IS THE FIRST YEAR OF THE NEW MOTOGP 800S AND, YES, the engines are now a bit smaller than last year, but no one is talking about displacement. Rather, all the chatter to date has been about the new tire and fuel regulations, as these areas have

affected the way the races have been run so far to a greater degree than any reduction in engine size.

Mainly intended to limit the cost of an all-out tire war, the new restriction of 31 tires per rider per weekend-14 fronts and 17 rears-has dramatically changed the nature of the competition itself. These rules apply to any tire manufacturer who has won at least two GPs in the dry since the start of the 2006 season; at the moment, that means Bridgestone and Michelin.

Each team and rider(s) must determine their tire choices on the Thursday afternoon of a race weekend before they have even turned a wheel. Decisions are made regarding carcass constructions and tread compounds based on previous experience. Most slicks now use a number of different compounds, and all variables must be considered. Each tire company has a good idea of how severe each circuit is on its product, the number of left and right corners, the way power is applied in each of those corners, thei nature and texture of the surface, and the way the surface is aging. Then, the weather must be considered. What is the forecast? How cold or hot will it be?

Different teams use different strategies to determine their tire selections. For example, at the start of this year, Yamaha decided to select its 17 rears according to a formula: two qualifiers, five of the construction the team thinks is likely to be best, and two groups of four tires that

can deal with either a different track temperature than the one predicted or other variables. As part of this strategy, Yamaha put into the mix two rears for more extreme conditions, bringing the total to 17. Michelin, its tire supplier, would prefer to have four tires set aside for these situations, even though it would reduce the allocations allowed elsewhere.

This is where it all gets interesting. If you are trying to choose a tire for a Sunday afternoon race, one of your major concerns will be the sort of track temperatures you would expect in the afternoon. Sometimes, especially at the start and the end of the season, there are big track temperature variations between morning and afternoon sessions. Under the new restrictions, it is quite possible that you simply won’t have tires that will work in the morning, when the track is cooler. Different compounds and constructions react differently to fluctuations in temperature, too.

In the past, tire companies have made products that were focused on a very tight temperature range. When the tire was operating at the right temperature, it was very grippy. The latest tires are not as narrowly focused, but they offer less ultimate grip as a result. That said, a difference of 10 degrees in the track surface temperature from their designed optimum will be well on the way to making them unusable.

In Jerez, Spain, the second round of the 18-race series, Yamaha’s Valentino Rossi quickly discovered that his three main groups of tires were not going to work; the temperature ranges were wrong. The two special choices would, in theory, be about right, but with only two tires, just one would be available for setup and one would be left for the race. It wasn’t until Saturday afternoon that Rossi could try one of the two spare tires, but it worked! Up to that point, however, he was reduced to trying to go fast on a bike with tires that wouldn’t grip and with the chassis settings distorted in an attempt to make them work.

So Yamaha’s strategy left it with a single usable tire for the race and at least eight unused, unusable rears. Even the two “good” tires had a question mark over their suitability; they were marginally too soft. Rossi was expecting to have difficulty in the latter half of the race, but it was overcast at mid-day in Jerez on Sunday, and the slightly cooler conditions meant that the one remaining tire was exactly what he needed. As a result, he took the win.

The problems are the same for everyone, of course, and hopefully more-stable summer temperatures will ease the situation. Each team will approach the situation with a different strategy; but one thing we can expect after the experience of the first few races is that there will be more practice sessions in which top riders will be languishing near the bottom of the order, trundling around on the wrong sort of tire while preserving their precious supply of what has turned out to be the “good ones” for the afternoon sessions and the race.

Upside of all this is that the new requirement for conservative choices and conservative tire design should make both racing and qualifying closer than everonce everyone gets used to the new system. The downside is that one tire factory is inevitably going to get the upper hand in the short term; so far, Bridgestone has had a better selection of compounds. This leads to inevitable comments from those who feel they’ve been hurt by the new regulations. Of the Michelin runners, Rossi has been the most vocal. Will the system last under pressure?

If tires were the controlling influence at tight, twisty Jerez, fuel was the limiting factor at the season opener in Qatar. The straight at Qatar isn’t the longest on the schedule, but at .6 of a mile it was certainly long enough to worry those teams concerned about their fuel range. This year, to go with the reduction in engine displacement from 990cc to 800, maximum fuel capacity has been reduced from 22 liters to 21. You might think that the smaller engines would drink less fuel, but that’s not necessarily so. For one thing, they can be held wide open for much longer than the 990s. Typically, the 800s are flat-out for 26 to 27 percent of each lap, 8 to 9 percent more than the 990s.

Revs are up, too. Last year, the Yamahas and Hondas were capable of 16,500 to 16,800 rpm; this year, the Honda is nearer 17,000 rpm but the Yamaha is capable of 18,000 if fuel is not an issue. Ducati, on the other hand, was over 17,000 rpm with its 990, but in early testing, the 800 saw up to 19,500. As soon as the serious testing started, the 800s were mapped for fuel efficiency, resulting in a lower exhaust note and slower speeds.

So, if we look at this simplistically, we have a 20 percent reduction in capacity but an increase in revs of between 2 and 15 percent, which at these high levels represents a serious increase in internal frictional losses. Add to that maximum throttle being used for a greater percentage of the lap, and the bikes will want to use almost the same amounts of fuel as last year’s 990s, except they have 1 liter, or nearly 5 percent, less fuel.

So, how do you make sure you have the best power from the available fuel, and how come the bike that has historically always struggled with the fuel limits is suddenly able to blitz the rest of the field on the straights? The answers are in the little things. After the Qatar race, there were lots of glum faces in the Yamaha pit; a last-minute, pre-race revision of the YZR-Ml’s fuel-map settings reduced peak revs to 17,500 rpm and severely and unnecessarily leaned out the fuel map. Second-place Rossi had just over 1 liter left in the tank after the celebration lap. His Dunlop-shod Yamaha colleagues, 15th and 16th in the race, respectively, used about 200cc more fuel, mostly due to additional wheelspin and a slightly higher redline of 17,600 rpm.

To keep all this in perspective, the factory Ducatis of race-winner Casey Stoner and non-finisher Loris Capirossi had about 300cc of fuel left after the victory lap; the remaining Kawasaki of Olivier Jacque didn’t finish its slow-down lap but was found to have nearly 1.2 liters of fuel remaining. The Hondas all had about 1 liter left.

Qatar was a 22-lap race, preceded by a sighting lap and an out lap. While you can certainly run the fuel down below 300cc with a well-designed tank, you do need to have a little sloshing around the bottom to ensure that the fuel pump picks it up under extreme braking or acceleration.

So, for a 22-lap race, the bikes actually completed 25 laps. If we assume a reduced fuel consumption of, say, half for the parade laps and 300cc left at the end of the race, we are looking at a worstcase fuel consumption of around 920cc per lap. At Qatar, a 5.38-kilometer cir-

cuit, that’s around 5.85 kilometers per liter. With a liter left, it looks as though Rossi achieved more like 6.3 km/1, or about 14 mpg.

From this experience, we are sure to see more risks being taken throughout the rest of the season on “remaining ftiel.” The next time we get to a fuel-critical circuit, we possibly will also see some very slow sighting and warm-up laps! There are technologies that allow the

fuel map to be changed in different sections of the lap-rich for full power on the straight, leaner (and more difficult to ride) in the twisties, or the other way ’round. A simple system would allow different rev limits depending on the gear selected. A more sophisticated system could use the sector lap markers (received automatically by the bike to show the rider his times) to set different maps for different sections of the racetrack depending on each team’s preferences.

GPS sensors would also work, but there are worries about the result should the signal be lost during a race. No one is admitting using the more complex systems, but that doesn’t mean they are not!

All the manufacturers will be capable of building fuel-efficient engines, but all have preferences as to how a bike should work “on-track.” Yamaha built a racebike that uses a backward-rotating crankshaft for agility and an irregular firing sequence for grip coming out of corners. Both of those decisions bring a small cost in fuel efficiency. The new Honda RC212V runs a 75-degree (give or take) Vee angle for mass centralization and quicker turning, but requires a balance shaft to deal with the resulting vibration. Even a high-quality balancer will use a little power. Both Yamaha and

Honda use valve-spring engines and have bodywork that gives maneuverability advantages in corners. Over in the power seat, Ducati’s 90-degree Vee doesn’t need

a balancer, doesn’t have any crank modifications for grip and turns forward. Ducati uses a “race-only” spring-free desmodromic system-another small efficiency improvement-and bodywork optimized for high speed. Its strategy, and the way its bike is built, is to make maximum power with maximum efficiency to win the straights and try to get in everyone else’s way in the corners. The other bikes are more balanced in the way they are designed and, as we saw in Jerez, should work better on twisty circuits.

Ducati had the right bike and the right fuel strategy for Qatar, Turkey and China; current points leader Casey Stoner is proving that he has exceptional throttlecontrol skills and that of all the Ducati riders, he alone can get the best out of a bike programmed to run on very weak fueling in the twisty sections of the track. But from now on, even without any engine tuning, the other teams will be planning fuel and power strategies that allow the use of more revs during the race and leave less in the tank at the end. Ducati will rule the straights for some time to come-the longer, the better-but over the next few races the others will most likely begin to close the gap. Provided, of course, they also choose the correct tires! □

For more MotoGP photos, visit www.cycleworld.com

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

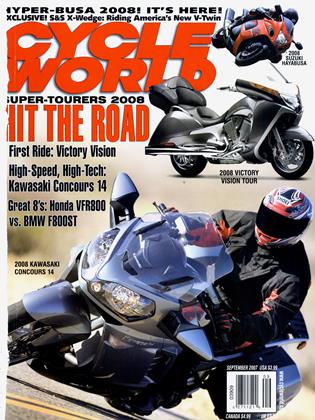

Up Front

Up FrontAnatomy of A Black Eye

September 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Trip To the New Barber

September 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTechnology Duel

September 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupSmaller, Lighter, Faster

September 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup2008 Street Trip

September 2007 By Blake Conner