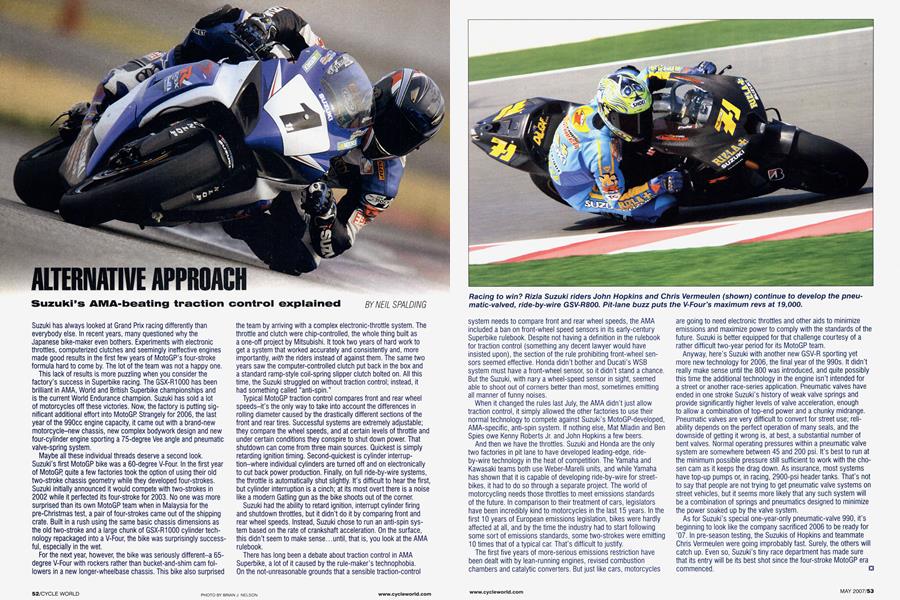

ALTERNATIVE APPROACH

Suzuki's AMA-beating traction control explained

NEIL SPALDING

Suzuki has always looked at Grand Prix racing differently than everybody else. In recent years, many questioned why the Japanese bike-maker even bothers. Experiments with electronic throttles, computerized clutches and seemingly ineffective engines made good results in the first few years of MotoGP’s four-stroke formula hard to come by. The lot of the team was not a happy one.

This lack of results is more puzzling when you consider the factory's success in Superbike racing. The GSX-R1000 has been brilliant in AMA, World and British Superbike championships and is the current World Endurance champion. Suzuki has sold a lot of motorcycles off these victories. Now, the factory is putting significant additional effort into MotoGP Strangely for 2006, the last year of the 990cc engine capacity, it came out with a brand-new motorcycle-new chassis, new complex bodywork design and new four-cylinder engine sporting a 75-degree Vee angle and pneumatic valve-spring system.

Maybe all these individual threads deserve a second look. Suzuki’s first MotoGP bike was a 60-degree V-Four. In the first year of MotoGR quite a few factories took the option of using their old two-stroke chassis geometry while they developed four-strokes. Suzuki initially announced it would compete with two-strokes in 2002 while it perfected its four-stroke for 2003. No one was more surprised than its own MotoGP team when in Malaysia for the pre-Christmas test, a pair of four-strokes came out of the shipping crate. Built in a rush using the same basic chassis dimensions as the old two-stroke and a large chunk of GSX-R1000 cylinder technology repackaged into a V-Four, the bike was surprisingly successful, especially in the wet.

For the next year, however, the bike was seriously different—a 65degree V-Four with rockers rather than bucket-and-shim cam followers in a new longer-wheelbase chassis. This bike also surprised

the team by arriving with a complex electronic-throttle system. The throttle and clutch were chip-controlled, the whole thing built as a one-off project by Mitsubishi. It took two years of hard work to get a system that worked accurately and consistently and, more importantly, with the riders instead of against them. The same two years saw the computer-controlled clutch put back in the box and a standard ramp-style coil-spring slipper clutch bolted on. All this time, the Suzuki struggled on without traction control; instead, it had something called “anti-spin.”

Typical MotoGP traction control compares front and rear wheel speeds-it’s the only way to take into account the differences in rolling diameter caused by the drastically different sections of the front and rear tires. Successful systems are extremely adjustable; they compare the wheel speeds, and at certain levels of throttle and under certain conditions they conspire to shut down power. That shutdown can come from three main sources. Quickest is simply retarding ignition timing. Second-quickest is cylinder interruption—where individual cylinders are turned off and on electronically to cut back power production. Finally, on full ride-by-wire systems, the throttle is automatically shut slightly. It’s difficult to hear the first, but cylinder interruption is a cinch; at its most overt there is a noise like a modern Gatling gun as the bike shoots out of the corner.

Suzuki had the ability to retard ignition, interrupt cylinder firing and shutdown throttles, but it didn’t do it by comparing front and rear wheel speeds. Instead, Suzuki chose to run an anti-spin system based on the rate of crankshaft acceleration. On the surface, this didn’t seem to make sense.. .until, that is, you look at the AMA rulebook.

There has long been a debate about traction control in AMA Superbike, a lot of it caused by the rule-maker’s technophobia.

On the not-unreasonable grounds that a sensible traction-control

system needs to compare front and rear wheel speeds, the AMA included a ban on front-wheel speed sensors in its early-century Superbike rulebook. Despite not having a definition in the rulebook for traction control (something any decent lawyer would have insisted upon), the section of the rule prohibiting front-wheel sensors seemed effective. Honda didn’t bother and Ducati’s WSB system must have a front-wheel sensor, so it didn’t stand a chance. But the Suzuki, with nary a wheel-speed sensor in sight, seemed able to shoot out of corners better than most, sometimes emitting all manner of funny noises.

When it changed the rules last July, the AMA didn’t just allow traction control, it simply allowed the other factories to use their normal technology to compete against Suzuki’s MotoGP-developed, AMA-specific, anti-spin system. If nothing else, Mat Mladin and Ben Spies owe Kenny Roberts Jr. and John Hopkins a few beers.

And then we have the throttles. Suzuki and Honda are the only two factories in pit lane to have developed leading-edge, rideby-wire technology in the heat of competition. The Yamaha and Kawasaki teams both use Weber-Marelli units, and while Yamaha has shown that it is capable of developing ride-by-wire for streetbikes, it had to do so through a separate project. The world of motorcycling needs those throttles to meet emissions standards of the future. In comparison to their treatment of cars, legislators have been incredibly kind to motorcycles in the last 15 years. In the first 10 years of European emissions legislation, bikes were hardly affected at all, and by the time the industry had to start following some sort of emissions standards, some two-strokes were emitting 10 times that of a typical car. That’s difficult to justify.

The first five years of more-serious emissions restriction have been dealt with by lean-running engines, revised combustion chambers and catalytic converters. But just like cars, motorcycles

are going to need electronic throttles and other aids to minimize emissions and maximize power to comply with the standards of the future. Suzuki is better equipped for that challenge courtesy of a rather difficult two-year period for its MotoGP team.

Anyway, here’s Suzuki with another new GSV-R sporting yet more new technology for 2006, the final year of the 990s. It didn’t really make sense until the 800 was introduced, and quite possibly this time the additional technology in the engine isn’t intended for a street or another race-series application. Pneumatic valves have ended in one stroke Suzuki’s history of weak valve springs and provide significantly higher levels of valve acceleration, enough to allow a combination of top-end power and a chunky midrange. Pneumatic valves are very difficult to convert for street use; reliability depends on the perfect operation of many seals, and the downside of getting it wrong is, at best, a substantial number of bent valves. Normal operating pressures within a pneumatic valve system are somewhere between 45 and 200 psi. It’s best to run at the minimum possible pressure still sufficient to work with the chosen cam as it keeps the drag down. As insurance, most systems have top-up pumps or, in racing, 2900-psi header tanks. That’s not to say that people are not trying to get pneumatic valve systems on street vehicles, but it seems more likely that any such system will be a combination of springs and pneumatics designed to minimize the power soaked up by the valve system.

As for Suzuki’s special one-year-only pneumatic-valve 990, it’s beginning to look like the company sacrificed 2006 to be ready for ’07. In pre-season testing, the Suzukis of Hopkins and teammate Chris Vermeulen were going improbably fast. Surely, the others will catch up. Even so, Suzuki’s tiny race department has made sure that its entry will be its best shot since the four-stroke MotoGP era commenced. □