SERVICE

Paul Dean

Whacking off

I’m curious to know something not touched on in the January Service department concerning the art and science of performance downshifting (“Sequential or rapid-fire?”). I recently recovered from a rash of coolness, but one thing bothered me while I was in rehab: The ruffians I used to go cruising with (they made the Girl Scouts look like Hell’s Angels) all practiced a downshift method wherein the clutch is never released between shifts. One fellow even commented that he didn’t want to “blow his engine” by downshifting, whatever that means.

My question is based on a couple of those characters who would find first gear at their earliest convenience. We might be booking along at 75 mph or so and, as we would approach a red light, the guy next to me would yank in the clutch and -‘Whack! Whack! Whack! Whack!”-bQ in first gear before he’d even slowed to 70 mph! Sure, he never let the clutch out, but isn’t that really bad for the lower gears and bearings? A Harley engine isn’t built to turn 30,000 rpm, so I don’t suppose the transmission parts are either, eh? Denny Joe Simpson Gilbert, Arizona

Geez, I never knew there was a 12-step program to overcome coolness. 1 've spent most of my life trying to acquire it.

Meanwhile, your former riding churns need to find a downshifting rehab program and enroll in it, because their technique is inflicting more damage on their transmissions than would just about any other method. All shifts, either up or down, engage the dogs of two gears that are spinning at different speeds; one set of dogs is turning at engine speed, the other at rear-wheel speed. In a conventional sequential (one gear at a time) upshift or downshift, the difference beween ratios is comparatively small, so the speed differential between engaging dogs also is small. But if all the downshifts are conducted at once, the speed differential between engaging dogs increases with each lower gear. This differential is maximized if the rider allows engine rpm to drop to idle while not scrubbing off much road speed; that reduces the rpm of the engine-driven gear to its minimum while the rear-wheeldriven gear is still turning at high rpm.

Thus, the repeated whacking noise you heard as your buddies shifted from fifth to first at high road speeds with the clutch disengaged and the engine idling was the clashing of engaging dogs. And that harsh noise is an indication of accelerated wear of those dogs.

In my previous reply regarding downshifting styles, I made no mention of possible damage caused by the all-at-once technique favored by some roadracers. That’s because if it is done right, there is very little or no damage to the transmission. Roadracers brake so hard when entering corners and their rate of deceleration is so great that the differential between engine speed and rear-wheel speed is never significant. By the time they reach the desired gear for any given corner, the bike already is at or near the proper speed for that corner. Besides, most roadrace bikes are so frequently torn down and refreshed that gear-dog wear is not usually a big concern.

Short-run Sportster

I have a 1995 Harley-Davidson Sportster 1200 with baffled drag pipes. I had the stock carb dialed-in for the pipes with a Keihin Tuner Kit when the bike was new. I put 30,000 miles on the bike before this problem appeared: Within 2 or 3 miles of start-up, hot or cold, the motor dies. If I wait 4 or 5 minutes, it will restart, but only with a lot of cranking. It doesn’t stop without waming-that is, it doesn't quit running as if the ignition were turned off; it instead sputters a couple of times and then goes dead. Trying to catch the motor in gear while still drifting produces no fire, just dead-motor turning with no backfire or sputtering. This is getting dangerous, as I live in a busy area.

Robert Echard Washington. D.C.

I suspect that the vent in your Sporty> ’s gas cap is malfunctioning. The vent is a one-way valve that allows outside air to enter the tank and replace the volume of gasoline that is consumed through normal running; but for emissions purposes, the vent does not allow gas vapors to exit the tank into the atmosphere. If the vent is clogged or stuck closed, the pressure inside the tank quickly drops to the point where it is significantly less than atmospheric, and that pressure differential prevents fuel from flowing out of the tank and into the carburetor float bowl. The bike will sputter and quit when that happens; but if the vent is only partially clogged and the bike sits with the engine off for a few minutes, enough fuel will dribble into the float bowl to allow the engine to restart and run, but only long enough to sputter and stall again in a few miles or less.

To determine if the vent is working, simply unscrew the gas cap as soon as the engine begins to falter. If the sputtering clears up in a few seconds and the motor resumes normal running, you ’ll know that the vent is the culprit. In which case, don’t bother with trying to fix the vent; the gas cap is inexpensive, so just replace it.

If the engine continues to falter and dies after you loosen the gas cap, then the problem is likely in the fuel petcock. Your Sporty uses engine vacuum to pull on a diaphragm that opens an internal valve in the petcock, allowing fuel to flow from tank to carb. If the vacuum hose between carb and petcock is cracked, it will leak enough vacuum to prevent the diaphragm from fully opening, restricting fuel flow. Same goes for the diaphragm: If it’s cracked or split, it won’t pull the valve open far enough to allow sufficient fuel flow for continuous running.

Check the hose for cracks, and if it seems okay, remove the end of the hose that connects to the carburetor. Also remove the fuel line from the carb and stick the end in a small container, like a cup or a bottle. Clean the end of the vacuum hose and then suck on it with the petcock in the On or Reserve position; fuel should flow readily from the petcock into the container. If not, you’ll have to disassemble the petcock and examine the diaphragm. Once again, you might be better off to replace the petcock with one from the aftermarket. Pingel makes an excellent one that is not vacuum-operated and also provides a higher rate of fuel flow.

TidyBoz

Normally, I respect the opinions of the Cycle World staff, but your evaluation of Clearlnnovation’s AirBoz wasn’t very thorough, was it? Three high-strung inline-Fours? Why not try this doohickey on a V-Twin? Or a V-Four, a parallelTwin or a Triple? The concept makes some sense: Water in a flushing toilet spins counterclockwise because that’s naturally the most efficient way, so why should air through an intake be any different? I just think you came to your conclusion too quickly. Keith Hoekstra Mesa, Arizona

We tested the AirBoz only on inline-Four sportbikes for one incontestable reason: Clear Innovation doesn’t offer them for any other type of motorcycle. And I don’t understand what you mean when you say that we came to our conclusion “too quickly.” If we had continued testing the AirBoz over and over, do you think the results would have changed?

By the way, your toilet-flushing analogy doesn’t, uh, hold water. Having the water circle the bowl apparently is the best way to ensure that large pieces of solid matter suspended in a liquid suecessfully pass through a relatively small opening; but in an engine, the straighten and faster that air can enter the combustion chambers, the more power that engine is likely to make.

Miles to the max

I recently learned about a Honda Gold Wing that reached 573,000 miles on the odometer with only standard upkeep. I found this to be so interesting that I wondered if you folks at Cycle World, the number-one independent motorcycle magazine, conducted your own total mileage tests for all major motorcycle brands. If you have not, do you have recommendations for buyers as to how many miles they should expect from their motorcycles? I have always enjoyed the depth of your road test articles, and I think this statistic would be vital. George Batalis Valparaiso, Indiana

Great idea, George. Let ’s see what such a task would involve. We usually test somewhere around 100 bikes a year, and let’s just say, for purposes of this discussion, that the average bike could last 100,000 miles with proper care. That’s a cumulative total of 10,000,000 miles that would have to be put on our testbikes each year. If one tester were to ride 500 miles a day, every day, 365 days a year, he would only rack up about 183,000 miles a year. So, for us to accomplish 10,000,000 miles, we d need to have 55 full-time testers on the road every single day of the year.

That s unreasonable, of course. Besides, no one puts 100,000 miles a year on a bike; perhaps a three-year span is more rational. That still would require 18 or 19 full-time testers on the road every day, assuming that none of the bikes would exceed 100,000 miles. Based on the aforementiond 573,000-mile Gold Wing, it’s likely that many would continue far past the 100K mark. So, we wouldn’t be able to report our findings to our readers for at least three years, if not longer. By then, most of the affected models would have been changed in enough ways to render our findings outdated.

We try to address some of these concerns with our 10,000-mile long-term tests. But even those are difficult to complete in a reasonable time for a staff that has to focus on riding and testing a new batch of bikes each month. And we aren’t willing to turn testing over to outsiders, as that would cause us to lose control over the quality and integrity of the findings. In theory, your idea is tremendous; but in actuality, it would be impossible for us to implement.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1 ) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663, 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com, or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Letters to the Editor” button and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

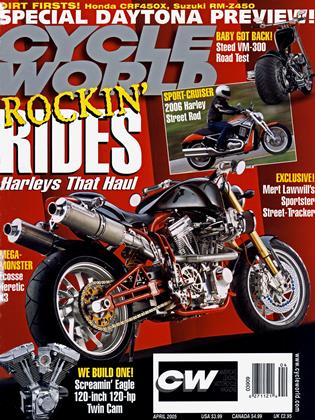

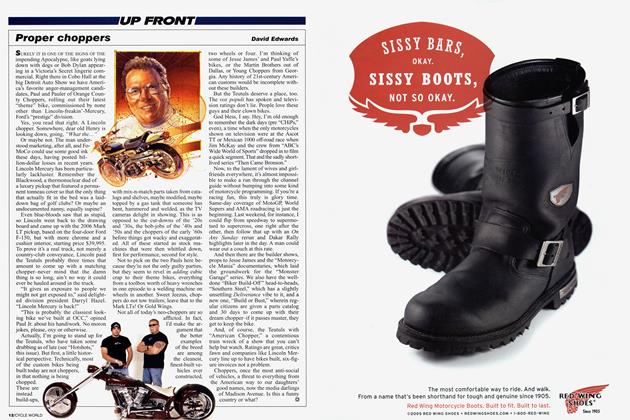

Up FrontProper Choppers

April 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSustainable Trailer Towing

April 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCApples & Crocodiles

April 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupRiding the Yamaha Mt-01

April 2005 By Damon I'anson -

Roundup

RoundupDream On

April 2005 By Brian Catterson