Not by Occident

EDITORIAL

THEIR DISPARAGERS CALL THEM BY

names that alliterate: Jap junk, rice rockets, Tokyo toys. And those are the nicer epithets many people use when referring to Japanese motorcycles. Some of the others are ones you don’t repeat in polite company.

Funny thing is, I agree—in principle, at least—with the thinking that makes some people hold Japanese bikes in such contempt; it’s simply a form of patriotism. In their minds, every Japanese bike sold is an American bike—i.e., Flarley-Davidson—not sold; every dollar invested in a “sushi sled” is a dollar that could have been spent on a bike made in the USA. They believe people should either ride American iron or not ride at all.

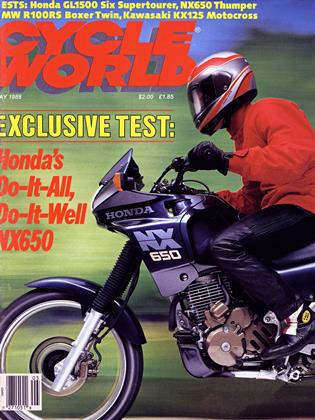

But in actual practice, I can’t buy that philosophy, simply because Flarley-Davidson doesn’t make enough different types of motorcycles to satisfy all my needs. I like Harley touring bikes enough to own one, and I’d be in Hawg heaven commuting or taking short excursions on any number of H-D Big Twins; but what happens when I want to slice up a twisty backroad or feel the rush of tripledigit horsepower? Or turn off the road to find out what’s at the end of a dirt trail? Or do a little production roadracing? Or play enduro rider in the desert? What Harley will let me do any of those things very well?

None that I know of. I do, admittedly, have an unusually wide range of motorcycling interests, whereas most riders tend to focus on one particular type of riding. But if Harley doesn’t happen to make a model that can satisfy any given rider’s needs, his only alternative is to buy something foreign-made. And the fact that so many of those riders have bought Japanese bikes over the past quartercentury is the main reason why motorcycling became a multi-billiondollar industry in this country. Even with today's depressed new-bike sales, motorcycling is still a big business.

Indeed, one way or another, the motorcycle industry provides jobs for a whole lot of Americans. And most of those jobs are somehow tied to Japanese bikes. All four of the Japanese manufacturers have distribution branches in this country that employ fairly large numbers of U.S. citizens; two of them even have factories here. And they all maintain dealer networks that provide employment for thousands of Americans nationwide.

American Honda, for instance, which also is in the automotive and power-products industries, has only about 250 people working exclusively with motorcycles; but many other of the company’s 3000 U.S. employees devote part of their time to motorcycle-related affairs (personnel, finance, R&D, etc.). That’s not counting all of the people who work for Honda’s 1500 or so U.S. dealers. And Honda’s car-and-bike manufacturing facility in Marysville, Ohio, employs an additional 4700 people, 375 of which work strictly in the motorcycle plant.

In truth, Marysville does not manufacture entire motorcycles; of the five models built there (all 1500 Gold Wings sold worldwide, plus U.S.-destined 1000 Hurricanes, 1100 and 800 Shadows and 750 Magnas), only the Gold Wing does not get preassembled engines from Japan, and all use Japanese-made suspensions and major electrical components. But their frames and gas tanks are made and painted in Marysville, while numerous other chassis bits, some lights and most plastic parts are either made there or sourced in the U.S. The Wing’s six-cylinder engine is assembled (and some of its components manufactured) in Marysville’s car/bike engine plant, which helps put bread on the table for another 425 Americans.

Kawasaki also has a U.S. manufacturing facility, in Lincoln, Nebraska, that employs 450 people. Lincoln builds frames, does all welding and painting operations, and assembles the bikes, but the engines and suspensions come from Japan. Eight models (all U.S.-bound Ninja 750s, Concours 1000s, 1200 and 1300 Voyagers, 750 and wire-wheel 1500 Vulcans, and KZ1000 police bikes, plus about one-third of the Ninja 600s) are built there, along with all Jet Skis and six ATVs. Kawasaki also employs more than 300 people in its U.S. distribution operation, and has a retail network 1000 dealers strong.

Neither Suzuki nor Yamaha currently builds motorcycles in the U.S., but both employ quite a few people at the distributor level (about 500 at Suzuki, more than 600 at Yamaha), and both have a sizable dealer network (around 1200 for Suzuki and 1600 for Yamaha). Harley-Davidson, meanwhile, has only 630 dealers nationwide, but employs 2400 people, and manufactures or buys most components here in the U.S. of A. I say “most” because some key H-D parts are not American-made. All front forks, rear shocks, carburetors and instruments, plus a few electrical components, are made elsewhere—in Japan, as a matter of fact.

It doesn’t take a mathematical genius, then, to see (hat Japanese motorcycles have considerable positive impact on the economy. Aside from the 2500 or so people the four firms employ directly, there are at least 20,000 employees in Japanese-bike dealerships around the country. Add to those numbers the people who work for aftermarket manufacturers and distributors, for wholesale and retail parts-and-accessory operations, for countless tune-up/repair-only shops across the country, and you've got thousands more who depend upon motorcycling for a living. Sure, some of these businesses are either largely or exclusively Harley-oriented; but without Japanese motorcycles, most would not exist.

I don’t suppose any of this will make Japanese-bike lovers out of Japanese-bike haters. But if they could just become Japanese-bikeerators, it would be a major step forward in the evolution of motorcycling—and of mankind. Paul Dean