Soul-Searching In The Engine Bay

EDITORIAL

YOU'VE READ IT. I AND OTHERS LIKE me have written it, more and more riders are saying it: A motorcycle needs to have some character, some emotion. A motorcycle needs soul.

Great. But have you ever tried to figure out just what gives a bike this . . . this soul? I have. And as far as I'm concerned, it isn't something found in the frame or the wheels or the gas tank or even in the paint (although I do have an irrational affection for almost any red motorcycle). Nope, for me, a bike’s soul is in its motor.

Without a motor, a motorcycle is just an inanimate lump of metal and rubber. Without a motor it has no personality, no life, no way of being easily distinguished from any other inanimate lump of metal and rubber. If you were to remove the engines from two bikes that live at opposite ends of the spectrum—say, a Kawasaki Mach III two-stroke Triple and a Cagiva 650 V-Twin four-stroke—and coast them down a hill, they wouldn't seem all that dissimilar, even though they’re from different eras and were built to do entirely different jobs. But with their motors installed and running, you couldn’t mistake one for the other if you were deaf, blind and brain-damaged. With a motor, each has an entirely different type of soul.

Much of that difference is the result of the way an engine feels to the rider, but I believe that most of it has to do with the way it sounds. And that’s a subject that has always intrigued me. I’ve had engineers all around the world explain to me why engine sounds vary so dramatically depending upon the number or placement of cylinders, and I've always understood them, but it still amazes the hell out of me. I mean, an explosion is an explosion; why should explosions sound so different because they happen in pairs rather than in fours, in an uneven rather than even sequence, in engines that have valves rather than ports?

But they do. And because they do, different kinds of engines have—for me, anyway—different kinds of soul. Some have a lot, some have none. Some have real emotion in the sounds they emit, others are as bland as reruns of Ozzie and Harriet.

Take two-strokes, for example. I know that they’re generally faster than four-strokes and far superior in most forms of racing; but unless I'm in a competitive riding situation, I don't like two-strokes much at all. They got no soul. Every time I hear a bunch of two-strokes buzzing around a racetrack, I get the impression that I'm eavesdropping on the annual mating ritual of all the world's chainsaws. And for my money, two-stroke streetbikes are little more than choked-up, muffled-down versions of two-stroke racebikes.

As you might imagine, then. I'm not in line to become The Lord of the Ring-Dings. But I don't get tearyeyed over all four-strokes, either, just some of them. Big Singles can have enough soul to move me, but only when they’re so unmuffled that they sound like a portable hammermill. Just about any high-performance inline-Four, however, can endear itself to me very easily. Fours have a distinct, purposeful demeanor that communicates a sense of excitement and urgency. They make me feel as though there’s a race about to happen and they’re in a hurry to be in it.

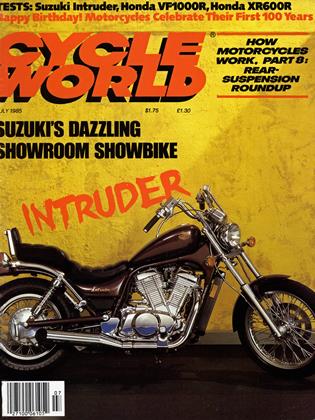

That’s not the case with opposedTwins, which sound as though nothing is happening and they're in no particular hurry to be part of it. They’re excellent motors, but they’re stuck with a flat, uninspiring exhaust note that does little to speed up my heart rate. And aside from the occasional well-tuned, open-piped Triumph or BSA racebike, vertical Twins don’t grab me emotionally, either. That goes double for vertical Twins with 180-degree crankshafts. which I find almost as annoying as two-strokes. And V-Fours with 360degree crankshafts—a group that encompasses all of Honda’s V-Four collection and Suzuki’s two Maduras— give off a featureless, lackluster drone that is totally lacking in any sort of emotion. How any one engine can make world-class high-performance seem utterly dead-boring is one of life’s great mysteries.

That's just the opposite of most VTwins, which can make mediocre performance a thoroughly enjoyable experience. Not with speed or handling or technology or opulence; with soul. V-Twins have that booming, staggered, unmistakable exhaust note and those ever-present power pulsations that keep you aware of precisely what the engine is doing at all times. You don’t need a tach to know if a V-Twin is running. VTwins are dripping with soul.

And so is the 1200cc, 180-degreecrank V-Four found in Yamaha’s VMax and Venture Royale—in my mind, the most soulful engine of all. It has the irregular, throaty rumble and sensuous throbbing of a V-Twin, combined with a boom and resonance that reminds me of another of my favorite motors—a high-performance automobile V-Eight. It’s too big and ugly to be of use in any kind of sport-riding machine, but I don’t care; I could sit and listen to its soulstirring exhaust music forever. That it happens to go like stink is simply a bonus, for I’d still feel the same about this engine if I never got it to full throttle or reached its redline rpm.

You may be skeptical of all this, wondering why anyone would ramble on about something so unimportant. But this is no trivial matter. The way in which a motorcycle communicates with its rider, through the way it sounds and feels, is just as important as how it runs and rides and steers and stops. If you ride only to go fast or to get from one point to another, you’re not likely to understand. But if you expect even a ride around the block somehow to be rewarding and enjoyable, you know what I’m talking about. You know that some motorcycles are better at it than others.

Because they’ve got soul.

—Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeThe Wrong Bag

July 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupMotorcycle Ergonomics: Trouble In the Fitting Room

July 1985 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

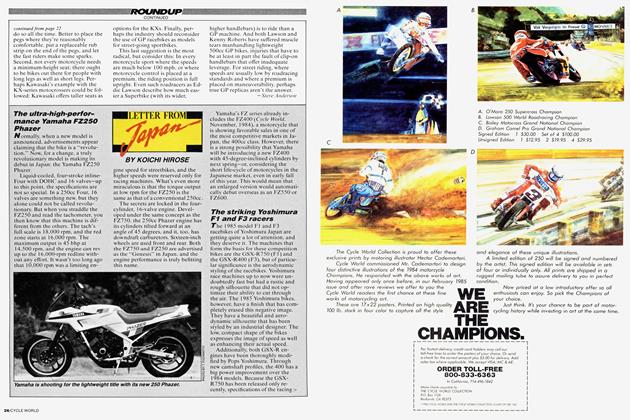

RoundupThe Ultra-High-Performance Yamaha Fz250 Phazer

July 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Striking Yoshimura F1 And F3 Racers

July 1985 -

Roundup

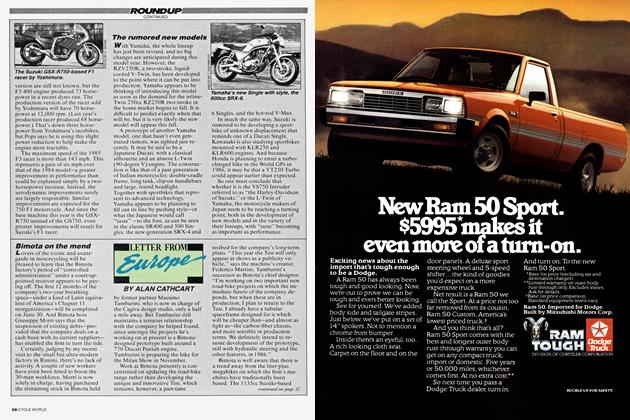

RoundupThe Rumored New Models

July 1985