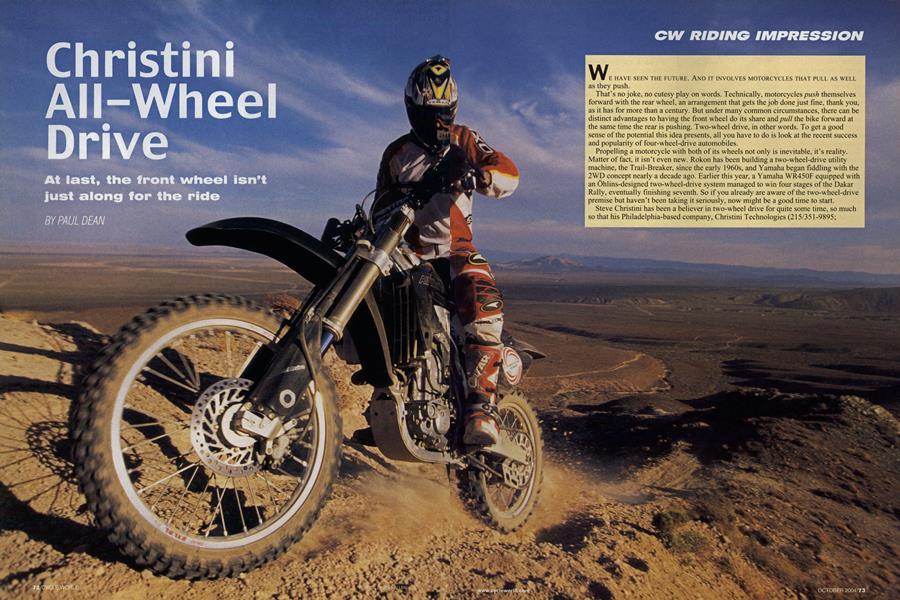

Christini All-Wheel Drive

At last, the front wheel isn't just along for the ride

PAUL DEAN

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

WE HAVE SEEN THE FUTURE. AND IT INVOLVES MOTORCYCLES THAT PULL AS WELL as they push.

That's no joke, no cutesy play on words. Technically, motorcycles push themselves forward with the rear wheel, an arrangement that gets the job done just fine, thank you, as it has for more than a century. But under many common circumstances, there can be distinct advantages to having the front wheel do its share and pull the bike forward at the same time the rear is pushing. Two-wheel drive, in other words. To get a good sense of the potential this idea presents, all you have to do is look at the recent success and popularity of four-wheel-drive automobiles. That’s no joke, no cutesy play on words. Technically, motorcycles push themselves forward with the rear wheel, an arrangement that gets the job done just fine, thank you, as it has for more than a century. But under many common circumstances, there can be distinct advantages to having the front wheel do its share and pull the bike forward at the same time the rear is pushing. Two-wheel drive, in other words. To get a good sense of the potential this idea presents, all you have to do is look at the recent success and popularity of four-wheel-drive automobiles.

Propelling a motorcycle with both of its wheels not only is inevitable, it's reality. Matter of fact, it isn't even new. Rokon has been building a two-wheel-drive utility machine, the Trail-Breaker, since the early 1 960s, and Yamaha began fiddling with the 2WD concept nearly a decade ago. Earlier this year, a Yamaha WR4SOF equipped with an Ohlins-designed two-wheel-drive system managed to win four stages of the Dakar Rally, eventually finishing seventh. So if you already are aware of the two-wheel-drive premise but haven't been taking it seriously, now might be a good time to start. Propelling a motorcycle with both of its wheels not only is inevitable, it’s reality. Matter of fact, it isn’t even new. Rokon has been building a two-wheel-drive utility machine, the Trail-Breaker, since the early 1960s, and Yamaha began fiddling with the 2WD concept nearly a decade ago. Earlier this year, a Yamaha WR450F equipped with an Öhlins-designed two-wheel-drive system managed to win four stages of the Dakar Rally, eventually finishing seventh. So if you already are aware of the two-wheel-drive premise but haven’t been taking it seriously, now might be a good time to start.

Steve Christini has been a believer in two-wheel drive for quite some time, so much so that his Philadelphia-based company, Christini Technologies (215/351-9895; Steve Christini has been a believer in two-wheel drive for quite some time, so much so that his Philadelphia-based company, Christini Technologies (215/351-9895; www. christini. com ), invented a system that has been in production now for several years-on bicycles. His pedalpower concept has proven so revolutionary that he felt it was time to apply the concept to the next logical candidate: the motorcycle. After R&Ding numerous prototype adaptations of his bicycle technology, he Finally arrived at a configuration he believes is

All-Wheel Drive

fully representative of what his design has to offer

motorcycling.

Christini calls his system going on here.

All-Wheel Drive, and the “mule” he has selected for

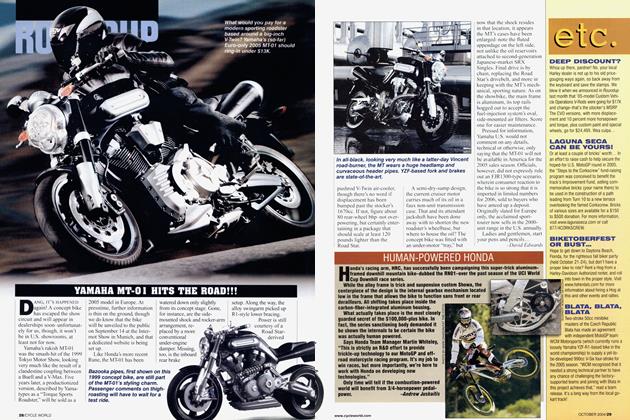

its latest iteration is a Honda CRF450R, a choice that speaks volumes about the legitimacy of the concept. It would have been easier and cheaper to roll out this idea on a less-powerful, non-competition-oricnted little foo-foo bike, but Christini didn't see the point in that approach. “If I was going to demonstrate that this system offers real performance advantages instead of just being an interesting novelty,” he says, “it had to be done on a serious off-road motorcycle. They don't get a whole lot more serious than this one.”

At First glance, Christini’s design, with its assorted collection of chains, gears, sprockets and shafts, seems unduly complex.

But after

closer scrutiny, it actually comes off as simple and straightforward. This is especially so, given the difficult challenge faced by any two-wheel-drive system: to power a single wheel that must pivot side-to-side while also traveling upand-down, and do so without adding considerable mass or inducing unfavorable steering and handling characteristics. Other than that, it’s a piece of cake.

Christini added his own criteria to that list: His system should be as invisible as possible and designed so that almost anyone with a modicum of mechanical know-how could access, understand and maintain it. He felt that the Öhlins design, in which a countershaft-driven pump powers a sophisticated hydraulic motor at the front hub, uses technology that most riders wouldn't understand and couldn’t service. And while the Rokon system of chains, chains and more chains is familiar and effective, it certainly fails the invisibility test.

In Christini’s AWD design, a chain driven by a second sprocket on the countershaft connects to another sprocket mounted to a right-angle gear drive up between the rear of the frame’s perimeter tubes, beneath the front of the scat. The right-angle drive then spins a driveshaft that runs up to the steering head where it turns a set of spiral-bevel gears, one atop the driveshaft gear, one below it. Using a shaftwithin-a-shaft design, each of the two driven gears is connected to its own dedicated sprocket, one above the other, located on the underside of the lower triple-clamp. Each of those sprockets drives a short chain that turns a long, thin driveshaft just ahead of the fork legs, one on the left and one on the right. The driveshafts are two-piece, telescoping units that can transfer power to the front wheel while allowing the front suspension to move unimpeded through its full travel. Finally, at the bottom end of each driveshaft is a machined housing that contains a set of spiral-bevel gears that drive the front hub.

In case you're wondering, the reason for having two driveshafts, one on each side of the wheel, is to allow the bike to be just as easy to steer in one direction as the other. Were there just one shaft, the engine torque transfered from a sprocket under the steering head to a driveshaft on one side of the fork would cause any steering inputs to be resisted in one direction and assisted in the other. “Torque steer,” it’s called. By using two driveshafts turning in opposite directions, the torque-steer forces of one side cancel those of the other, allowing the steering to be neutral.

All-Wheel Drive

In development, Christini determined that the system needed some kind of shockabsorbing medium to prevent damage to the entire driveline during the hard jolts of jump landings, stutter bumps and the like. To solve that problem, he incorporated a small clutch-consisting of a friction plate, a pressure plate and a preloadadjustable spring-on the right-angle gear drive under the seat. The clutch grips sufficiently for the delivery of power to the front wheel but momentarily slips any time the system is subjected to spike loads or too-sudden changes in wheel speed.

Christini also found that driving the front wheel at the same speed as the rear simply did not work; the

front tire wanted to plow, and the steering was impossibly sluggish and lacked the right kind of feedback. He and his team of engineers and test riders ultimately found that a front-drive ratio about 60 percent lower than that of the rear provided the best results. A slightly higher or lower ratio might be more suitable for certain conditions, but the 60 percent figure seemed the best overall compromise.

What this meant, then, was that the countershaft would be trying to drive the rear wheel 60 percent faster than the front. At 50 mph, for example, the front wheel would want to be going just 30 mph. That obviously was a recipe for disaster, so Christini installed a one-way sprag-clutch in the front-hub drive mechanism. The sprag permits the front wheel to turn faster than the drive mechanism but won’t allow it to turn slower. So, any time the rear wheel has good traction, the front wheel just freewheels along as it would on a rearwheel-drive bike. But when the rear wheel loses enough

traction to cause sufficient wheelspin, the front-wheel drive begins to engage and pull the bike forward. The end result is better acceleration than the bike would have with rear drive alone.

That’s the theory, at least; but how does it work in actual practice, you ask? We had a chance to spend a day on Christini’s AWDequipped

CRF45OR in various off-road settings and

came away very

impressed indeed. When conditions were undemanding, the system was transparent, allowing the bike to behave almost identically to a stock 450. The steering feels the same, the handling is unchanged and the overall performance is virtually the same. Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis thought that the AWD 450 may be just a wee bit more nose-heavy on certain jumps or whoops, and that could be attributed to the 4 pounds of front unsprung weight the system adds. He didn't really feel the 13-pound overall weight increase, however, since the bulk of that mass is distributed close to the bike’s center of gravity.

Lewis commented that most riders might not even notice the AWD system at first, but that they would detect a significant difference once they began riding it pretty hard. “For one thing,’’ he said, “you can start your comer slides early, and once you get back on the power, you can feel the front wheel pulling the bike around the turn. It allows you to do big powerslides better and faster, kinda like what those four-wheel drive rally cars do when you watch them on television."

All-Wheel Drive

Jeff Allen, Assistant Manager of our Photo Services Department, was completely blown away by the performance of Christini’s AWD 450. In addition to his unquestionable skills as a photographer. Allen also is a highly capable off-road rider who can push a bike close to its limits. “For me, the most impressive thing about this two-wheel-drive machine isn’t so much what it does but what it doesn 7 do,” he said. “It doesn’t do some of those things that can slow a rider down, like the frequent slip-grab-slip-grab business that a rear-wheel-drivc bike does on slippery surfaces. Two-wheel-drive either reduces that effect or eliminates it altogether. It’s especially good on slow, slick off-camber turns that normally cause the rear wheel to spin and slide downhill as soon as the throttle is applied. When that starts to happen with the Christini system, the front-wheel drive kicks in and pulls the bike up and around the turn.”

Allen was equally impressed with the way the AWD Honda wants to go straightcr than its 2WD counterpart in rocky, rutted terrain. The front wheel had much less tendency to get knocked to one side or the other over rocks, and it sometimes seemed more able to climb up out of ruts rather than getting stuck in them. And both he and Lewis said that for starting out from a dead stop on a steep uphill, it was the best thing they had ever ridden.

“This bike is so good that if some company would put two-wheel drive on a motocrosser right now,” proclaimed

Allen, "it would he banned after the first race. But if they were avail able right now, I'd buy one in a heartbeat."

That won’t happen “right now,” but Christini is working hard to make it happen soon. He’s been demonstrating the system to any bike manufacturer that will give him an audience, and he’s also exploring other ways in which he might partner with someone to help get the concept into production.

He also makes it clear to everyone that what they see on his CRF450R is not a production system. “Most of the components are off-the-shelf items available from industrial hardware suppliers,” he says. “The only things we made were the gears and housings for the wheel hubs, and the triple-clamps. I wanted to show people that the system really works, but we’re a small company without a huge budget, so we couldn’t afford to make all the parts ourselves. But that also validates the soundness of this design: It works really well, even without purpose-built pieces.”

Lewis couldn’t agree more. “After just 10 minutes of riding Christini’s bike,” he said. “I was convinced that twowheel-drive is the future of off-road riding, even though the concept is not yet fully developed.”

From a man who unquestionably is one of the world’s most accomplished off-road riders, that’s sky-high praise. And if Steve Christini has his way, the future that Lewis predicts might be just around the comer. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue