LEANINGS

Another green Triumph

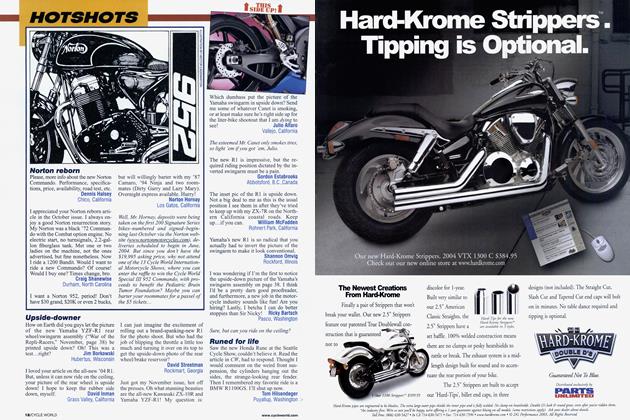

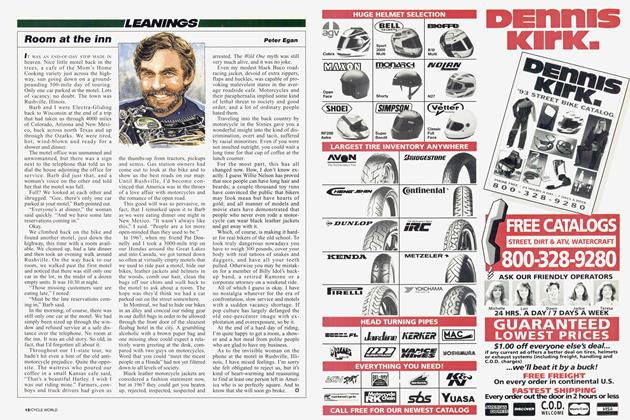

Peter Egan

I HAVE OFTEN SAID—AND PROBABLY AT least once in these pages—that the next motorcycle we buy is very often a form of revenge for our last long trip. For instance, if the seat was too hard or the windflow over the windshield was too deafening on that last big ride, a person might be tempted to go out and buy a more luxurious and quiet motorcycle for the next cross-country adventure.

Last week, however, I bought a new motorcycle not because it’s different from the last bike I took on a long trip, but because it’s essentially identical: a reward rather than a revenge.

The trip in question was a travel story that Editor Beau Pacheco asked me to do for CW\s sister annual, Motorcycle Travel & Adventure. “I’d like you to pick up a new Triumph Bonneville in Nashville,” Beau told me, “and ride it down to Memphis, then take a long, rambling trip through the Mississippi Delta and do a story on searching for the roots of the Blues.”

Persuasiveness is Beau’s long suit, so I left about 15 minutes later on the trip. As a hard-core blues fan with a weakness for Triumphs and British bikes in general, I was an easy mark. Also, I’d been curious about the new Bonneville, wondering if it could flourish as an all-purpose, do-everything motorcycle, or if it were essentially a retro-toy for cruising around on warm summer evenings and trying to relive some elusive magic from one’s youth.

Long story short, I was surprised how much I liked the new red-and-silver Bonneville on my trip to Mississippi. The weather was cool and wet, but even this failed to dampen the amount of fun I had on the ride. The road probably helped. Instead of shooting from Nashville down to Memphis on the interstate, I headed out on Highway 100. This is a winding, picturesque road that sweeps and dips through small towns in the tapering foothills of the Appalachians until it finally bottoms out in the flat, fertile cotton land of the Mississippi Delta. Vine-covered bridges cross rivers whose names suggest the ghosts of Indian tribes and Stephen Foster songs.

You spend a long time on this road flicking through successive bends, lofting blind hills and descending into curving tunnels of dark green trees hung with kudzu vines. It’s a good place for a smooth, torquey Twin you can move around on, a motorcycle with mediumwide bars and a slightly upright riding position for maximum scenery absorption. It was perfect for the Triumph, and I would rate this as one of the four or five best rides I’ve ever taken-one of those rare times when your mood, the road and the bike all coalesce into a kind of dripfeed of inexpressible pleasure that lasts all day long, and into the next.

I spent long hours in the saddle of this bike and never found it tiring or boring. And each morning it was newly inviting, like the road itself. So I stuck that information about the Triumph in the back of my mind and let it ferment there, like a slow-bubbling vat of sour mash.

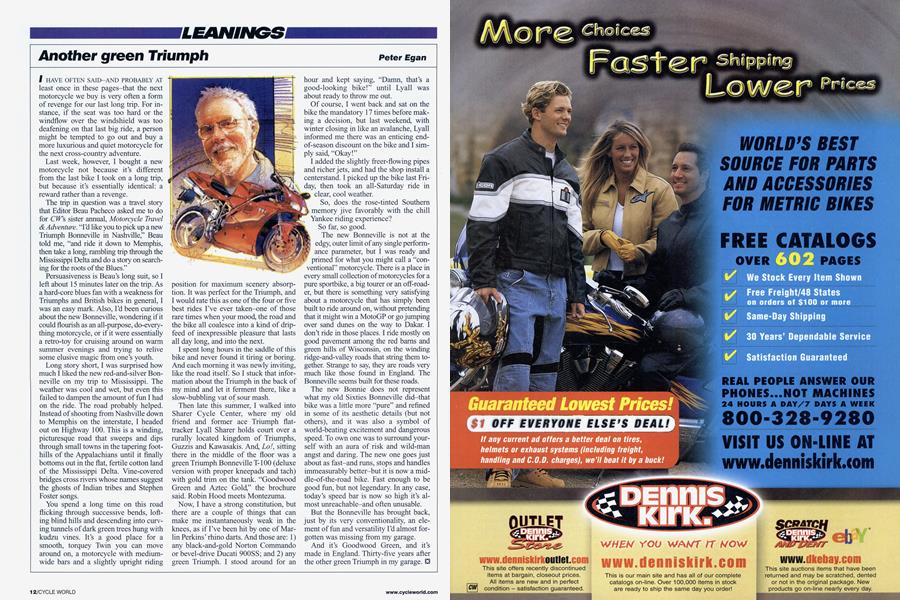

Then late this summer, I walked into Sharer Cycle Center, where my old friend and former ace Triumph flattracker Lyall Sharer holds court over a rurally located kingdom of Triumphs, Guzzis and Kawasakis. And, Lo!, sitting there in the middle of the floor was a green Triumph Bonneville T-100 (deluxe version with proper kneepads and tach) with gold trim on the tank. “Goodwood Green and Aztec Gold,” the brochure said. Robin Hood meets Montezuma.

Now, I have a strong constitution, but there are a couple of things that can make me instantaneously weak in the knees, as if I’ve been hit by one of Marlin Perkins’ rhino darts. And those are: 1) any black-and-gold Norton Commando or bevel-drive Ducati 900SS; and 2) any green Triumph. I stood around for an hour and kept saying, “Damn, that’s a good-looking bike!” until Lyall was about ready to throw me out.

Of course, I went back and sat on the bike the mandatory 17 times before making a decision, but last weekend, with winter closing in like an avalanche, Lyall informed me there was an enticing endof-season discount on the bike and I simply said, “Okay!”

I added the slightly freer-flowing pipes and richer jets, and had the shop install a centerstand. I picked up the bike last Friday, then took an all-Saturday ride in clear, cool weather.

So, does the rose-tinted Southern memory jive favorably with the chill Yankee riding experience?

So far, so good.

The new Bonneville is not at the edgy, outer limit of any single performance parameter, but I was ready and primed for what you might call a “conventional” motorcycle. There is a place in every small collection of motorcycles for a pure sportbike, a big tourer or an off-roader, but there is something very satisfying about a motorcycle that has simply been built to ride around on, without pretending that it might win a MotoGP or go jumping over sand dunes on the way to Dakar. I don’t ride in those places. I ride mostly on good pavement among the red bams and green hills of Wisconsin, on the winding ridge-and-valley roads that string them together. Strange to say, they are roads very much like those found in England. The Bonneville seems built for these roads.

The new Bonnie does not represent what my old Sixties Bonneville did-that bike was a little more “pure” and refined in some of its aesthetic details (but not others), and it was also a symbol of world-beating excitement and dangerous speed. To own one was to surround yourself with an aura of risk and wild-man angst and daring. The new one goes just about as fast-and runs, stops and handles immeasurably better-but it is now a middle-of-the-road bike. Fast enough to be good fun, but not legendary. In any case, today’s speed bar is now so high it’s almost unreachable-and often unusable.

But the Bonneville has brought back, just by its very conventionality, an element of fun and versatility I’d almost forgotten was missing from my garage.

And it’s Goodwood Green, and it’s made in England. Thirty-five years after the other green Triumph in my garage. □