A DAY AT THE SPEEDWAY

The Roar of the Bleachers, the Smell of the Ground

Peter Egan

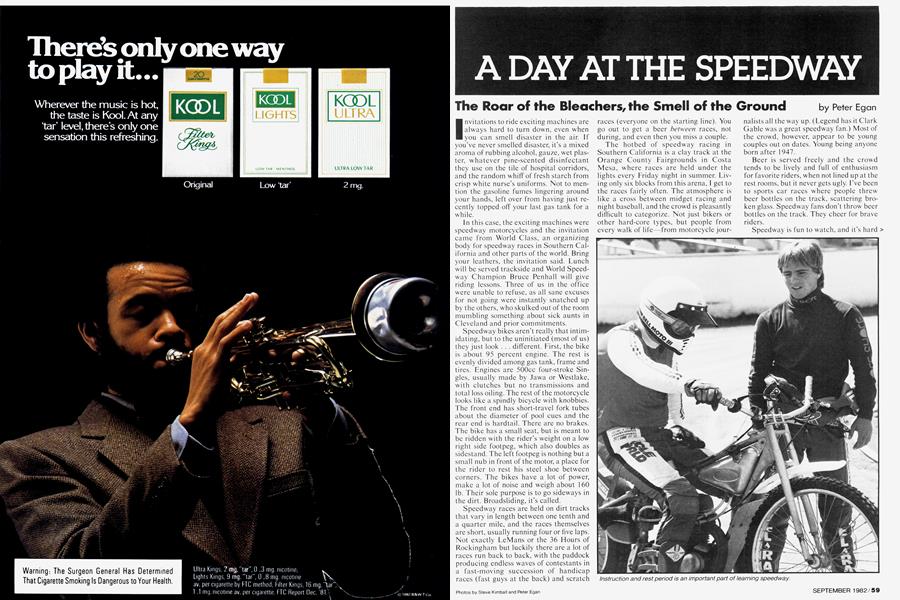

Invitation to ride exciting machines are always hard to turn down, even when you can smell disaster in the air. If you’ve never smelled disaster, it's a mixed aroma of rubbing alcohol, gauze, wet plaster, whatever pine-scented disinfectant they use on the tile of hospital corridors, and the random whiff of fresh starch from crisp white nurse’s uniforms. Not to mention the gasoline fumes lingering around your hands, left over from having just recently topped off your last gas tank for a while.

In this case, the exciting machines were speedway motorcycles and the invitation came from World Class, an organizing body for speedway races in Southern California and other parts of the world. Bring your leathers, the invitation said. Lunch will be served trackside and World Speedway Champion Bruce Penhall will give riding lessons. Three of us in the office were unable to refuse, as all sane excuses for not going were instantly snatched up by the others, who skulked out of the room mumbling something about sick aunts in Cleveland and prior commitments.

Speedway bikes aren’t really that intimidating, but to the uninitiated (most of us) they just look . . . different. Lirst, the bike is about 95 percent engine. The rest is evenly divided among gas tank, frame and tires. Engines are 500cc four-stroke Singles, usually made by Jawa or Westlake, with clutches but no transmissions and total loss oiling. The rest of the motorcycle looks like a spindly bicycle with knobbies. The front end has short-travel fork tubes about the diameter of pool cues and the rear end is hardtail. There are no brakes. The bike has a small seat, but is meant to be ridden with the rider’s weight on a low right side footpeg, which also doubles as sidestand. The left footpeg is nothing but a small nub in front of the motor, a place for the rider to rest his steel shoe between corners. The bikes have a lot of power, make a lot of noise and weigh about 160 lb. Their sole purpose is to go sideways in the dirt. Broadsliding, it’s called.

Speedway races are held on dirt tracks that vary in length between one tenth and a quarter mile, and the races themselves are short, usually running four or five laps. Not exactly LeMans or the 36 Hours of Rockingham but luckily there are a lot of races run back to back, with the paddock producing endless waves of contestants in a fast-moving succession of handicap races (fast guys at the back) and scratch

races (everyone on the starting line). You go out to get a beer between races, not during, and even then you miss a couple.

The hotbed of speedway racing in Southern California is a clay track at the Orange County Fairgrounds in Costa Mesa, where races are held under the lights every Friday night in summer. Living only six blocks from this arena, I get to the races fairly often. The atmosphere is like a cross between midget racing and night baseball, and the crowd is pleasantly difficult to categorize. Not just bikers or other hard-core types, but people from every walk of life—from motorcycle jour-

nalists all the way up. (Legend has it Clark Gable was a great speedway fan.) Most of the crowd, however, appear to be young couples out on dates. Young being anyone born after 1947.

Beer is served freely and the crowd tends to be lively and full of enthusiasm for favorite riders, when not lined up at the rest rooms, but it never gets ugly. Fve been to sports car races where people threw beer bottles on the track, scattering broken glass. Speedway fans don’t throw beer bottles on the track. They cheer for brave riders.

Speedway is fun to watch, and it’s hard > to figure why the sport fills grandstands in England and California but hasn’t spread to the rest of the U.S., like stock car racing, which has been around for about the same number of years, i.e., since motorcycles and cars were invented. Organizers such as Harry Oxley, the man who revived speedway racing in Orange County, have been asking themselves the same question. Which is why they invited members of the motorcycle press to attend a lunch and practice riding session on a weekday afternoon at the Orange County Fairgrounds. At least if I were injured, I’d be within limping distance of home.

Invitations in hand and hungry for lunch, Ed. Girdler, Steve Kimball and I loaded our leathers into the CWtruck and headed for the track. Penhall and friends were waiting trackside with several bikes for us to ride, as well as a few spare steel shoes for sliding left feet. Bruce Penhall. the reigning World Speedway Champion, took the title at Wembly Stadium near London last year in front of 93,000 cheering spectators and a world TV audience. He is a young man with the kind of healthy good looks normally reserved for surfing champions, movie stars or people who tell you to buy Crest with Fluoristan, and he is also the first American to become World Champion since Jack Milne took it in 1937. Like Ali (aka Clay) in his time, he looks too unmarked and healthy to do what he does for a living.

Penhall showed us around the bikes. Clutch, throttle, no brakes. Big right footpeg, little left footpeg. “You stand up with all your weight on the right leg,” he told us. “Keep that right leg ramrod straight—don’t bend at the knee—and lean forward over the bars when you ride. Use the throttle to bring the back end out in the corners. Don’t sit down on the seat in the corners; leg straight and lean forward. Keep the left foot out skimming over the track in the corners, but don’t let it get behind the engine cases. Keep it forward.”

Penhall bump started his bike and did a few quick demonstration laps, broadsliding the corners practically backward and lofting the front wheel on the short straights, roaring around and flinging dirt. You could almost hear the collective gulp from the gathered press when he shut his engine down. I wondered if it was too late to have a sick aunt in Cleveland. We lined up to put on the steel shoe and take lessons.

Having always been a slow learner (which reads a lot better than “clumsy”), I established early in life a set procedure for gaining mastery over fast vehicles. The drill was an orderly succession of the following five steps: ( 1 ) start slowly, (2) build confidence, (3) go faster and (4) enjoy a brief moment of speed euphoria just before you (5) crash your brains out. Cars, bikes, go-karts, it didn’t matter. That was the check list. If you survived the crashing stage without hearing bells and holding imaginary conversations with famous historical figures, you gradually got better.

It was therefore with a twinge of misgiving that I strapped on the steel shoe. There wouldn’t be much time to build confidence, go faster or enjoy euphoria. It looked like an opportunity to go straight from starting slow to crashing. In my favor, I’d spent a great deal of time one summer sliding a Honda Super 90 around an abandoned baseball diamond, so I figured sliding a speedway bike around couldn’t be all that hard.

Strapping on the steel shoe, it turned out, caused more a twinge of pain than misgiving. The only steel shoe available was made to fit a size 8'/2 boot and I wear a size 10, so like one of Cinderella’s ugly sisters I had to jam a borrowed size 8V2 roadracing boot on my left foot. Contrasted with the giant motocross boot on my right, it made me look like Jack Hawkins in Treasure Island. All I needed was a parrot on my shoulder. Having forgotten all fear and wanting only to get that 8 V2 boot off my foot, I hobbled out onto the track for my lesson.

Riding a speedway bike, it turned out, is not like riding a Honda Super 90 around an abandoned baseball diamond. Not sitting down is the first and foremost difference in riding a speedway bike. In normal dirt technique you sit upright on the seat, initiate a slide with a touch of rear brake, turn right to go left, lay the bike over a bit, and roll the power on to control back end movement, keeping the left foot out and forward. Done on a good surface at moderate speed, it can be a fun and fairly lazy maneuver. Your body moves with the seat and you can easily see the angle of the bike relative to the handlebars and you have a seat-of-the-pants feel for the sliding of the back tire.

On a speedway bike you stand bolt upright on the outside peg and lean way out over the bars. None of the bike is in view, unless you care to peer straight down at the steering head and front wheel, which look a long way down. Your first reaction is to feel overly tall, as though your head is traveling through the air about 10 feet off the track, propelled by a motorcycle you cannot see. Nearly all of the bike is well behind you, so it’s hard to get a feeling for what it’s doing or where it’s going, except through the movement of your stiff right leg. Sort of like driving a long semi on an icy road with a small cab and no mirrors; there’s a lot going on behind you.

After the sensations of tallness and remoteness wear off, the next phenomenon to set in is fatigue. Standing on one leg and leaning forward while riding a bike is very tiring, like one of those invented exercises doctors use to increase your heartbeat and get your life insurance cancelled. The only two things I’ve done equally as exhausting per minute spent are high school wrestling and rock climbing when you are in a very bad place. After three practice laps I started hoping Penhall would call me in to give me some advice, which he did.

“Pitch it sideways more and give it more throttle,” he said.

“What?”

“Pitch it sideways more and give it more throttle.”

I’d heard him clearly the first time, but I needed a few more seconds to rest. Each time I came in for advice my hearing got worse.

After a few more laps I began to feel a little more comfortable and play with the power a bit. I say a bit because the acceleration from the 500cc Jawa is more than enough to get your attention on a tiny tenth mile track. Throttle response is torquey and instantaneous, pushing the bike ahead in wheelspinning lunges. As there are no brakes, power is needed to turn the bike in the corners. If you come down the short straight quickly and then back off and try to coast through the corner on normal steering the bike goes wide and you end up barely avoiding the wall. Opening the throttle gets the bike sideways and pushes it off in the direction you want to go.

Usually.

Sometimes it just lights up the back tire and dumps you on your ear. As I discovered going into the far turn. When you ride a speedway bike your wrist is cinched with a piece of string to a “dead man switch” on the handlebars. If you become separated from the bike, the string yanks a spring-loaded ball out of the switch and the bike stops running so it doesn’t run amok and tear somebody up with its back tire. Luckily the dead man switch can be operated by living individuals with no ill effect on the vital signs. We bumpstarted the bike and got it running again, no damage done.

Real speedway riders come around corners with the bike completely sideways, almost backing it into turns. Doing that, I realized takes a lot of speed going into the corner and precise throttle control once you're there, not to mention practice—all of which 1 was lacking. The odd riding position and the straight-leg posture no doubt work. Speedway guys have spent a lot of time getting this so it works very well for them. With enough practice it would make sense, just the way a street bike or a trials bike makes sense for its use. But speedway takes some getting used to. Fifteen or 20 laps is just enough to engender great respect for the skill and bravery of the pros without actually teaching you how to do it.

The Good Editor and Steve Kimball took their turn with the Iron Maiden shoe and the riding lesson also. When Kimball forced his size 1 1 foot into the same shoe I'd been wearing, I thought his helmet was was going to pop off. I've never seen anybody hobble so pathetically, or walk on feet so badly mismatched in size. He and Ed. Girdler went about as slowly as I did and were equally chastened in their dreams of speedway glory. One journalist, Mark Kariya from Cycle News, went out and built up respectable speed and style during his practice session, looking like a good novice class competitor. Then he went out for a second practice session and looked even faster, just before he crashed. At least he appeared to have a brief moment of speed euphoria.

Next time I go back to the Fairgrounds I think I’ll leave my boots and leathers at home. I’ll put on some comfortable tennis shoes and blue jeans, take a stroll over there and sit in my favorite bleacher down near Corner One. If it’s a warm night I might have a cold beer with my peanuts and hot dog. It’ll be fun watching Bruce Penhall and all those other guys who know what they’re doing stand on one ramrod-stiff leg and slide sideways on the hard packed clay, racing flat out within inches of the wall. For the price of a movie, the best bargain in town is not being out there. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue