The Indian Chief

You’ll Never Wear Out The Indian Scout, Or Its Brother The Indian Chief. They're Built Like Rocks, To Take Hard Knocks. It’s the Harleys That Cause the Grief.

Bob Stark grew up around Indians. His father became an Indian dealer in 1918. It was only natural that Bob wanted an Indian when he was growing up and when he rode his Cushman scooter down the streets of Akron, Ohio he always had his eye out for Indians. In 1950 there weren’t an excess of Indians around, so when Bob saw a 1948 Chief parked at a used car lot, he became very excited. It only had a little over 1100 mi. on the odometer, having been owned by a young man then in the army. Sell the Indian and buy yourself a car, the young fellow wrote his mother, so the Indian was at the dealer’s lot, trying to fetch $450. That was the bike for him, Bob knew.

Saving his money from whatever odd job he could land, he gradually accumulated cash, almost enough for the Indian. He was a regular visitor to that car lot as he hit the $400 mark. But then the Indian was sold. His dream was gone, months after it first appeared. Within a few weeks Bob found another Chief, a ’46 model. It was good enough to get by, certainly removing him from the ranks of Cushman and Whizzer riders and sending him down the Indian trail. But somehow he still wanted a ’48, painted Indian red, so a year later when he saw an, ad in the local paper for a ’48 Indian Chief he had to go look at it. When he arrived, it turned out to be the Chief from the used car lot, with 88 additional miles on the odometer and a $325 price. Naturally, he bought it. Surprisingly, he still owns that Chief 31 years later.

That isn’t the only bike Bob has, though. His garage is filled with several Indians, at least as many Whizzers and a few other machines. Down at Starklite Cycles, Bob’s Indian shop, there are scores of other Indians, plus parts for several dozen more. In the various warehouses around the Fullerton, California shop are more Indians. Depending on what day you catch him, Bob owns somewhere around three dozen Indians, plus an odd assortment of other old motorcycles.

Steve Kimball

There is something enchanting about Indians that can make a normal motorcycle enthusiast just a little irrational. It’s been nearly 30 years since the last Indian was made in Massachusetts, yet there are shops that still rebuild Indians and people are still buying these rebuilt Indians. Just what is so special about these machines?

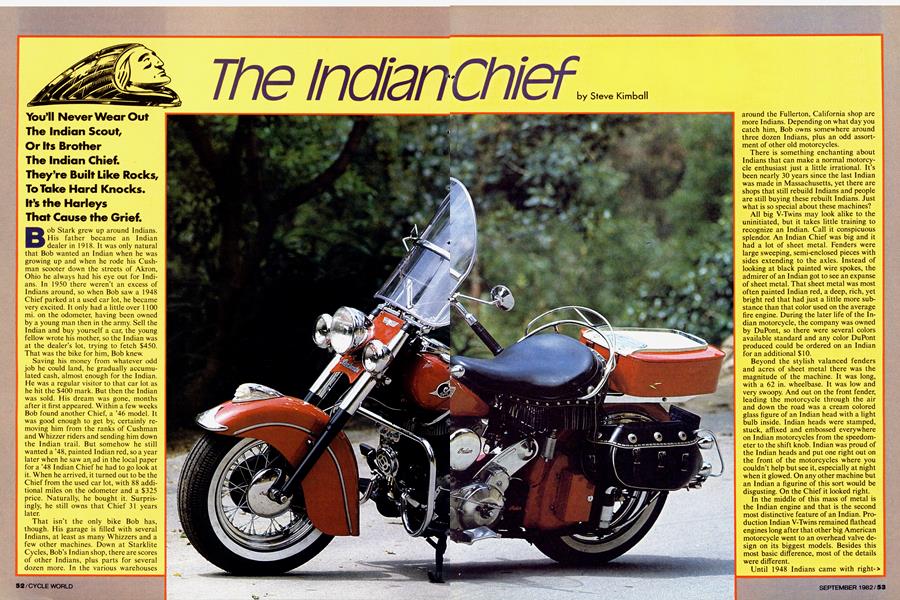

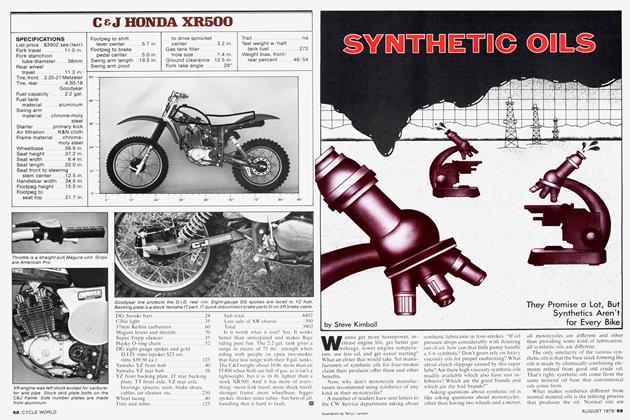

All big V-Twins may look alike to the uninitiated, but it takes little training to recognize an Indian. Call it conspicuous splendor. An Indian Chief was big and it had a lot of sheet metal. Fenders were large sweeping, semi-enclosed pieces with sides extending to the axles. Instead of looking at black painted wire spokes, the admirer of an Indian got to see an expanse of sheet metal. That sheet metal was most often painted Indian red, a deep, rich, yet bright red that had just a little more substance than that color used on the average fire engine. During the later life of the Indian motorcycle, the company was owned by DuPont, so there were several colors available standard and any color DuPont produced could be ordered on an Indian for an additional $10.

Beyond the stylish valanced fenders and acres of sheet metal there was the magnitude of the machine. It was long, with a 62 in. wheelbase. It was low and very swoopy. And out on the front fender, leading the motorcycle through the air and down the road was a cream colored glass figure of an Indian head with a light bulb inside. Indian heads were stamped, stuck, affixed and embossed everywhere on Indian motorcycles from the speedometer to the shift knob. Indian was proud of the Indian heads and put one right out on the front of the motorcycles where you couldn’t help but see it, especially at night when it glowed. On any other machine but an Indian a figurine of this sort would be disgusting. On the Chief it looked right.

In the middle of this mass of metal is the Indian engine and that is the second most distinctive feature of an Indian. Production Indian V-Twins remained flathead engines long after that other big American motorcycle went to an overhead valve design on its biggest models. Besides this most basic difference, most of the details were different.

Until 1948 Indians came with righthand tank shifts and lefthand throttles, though it was easy to convert an Indian to the Harley-style lefthand shift. After 1948 the big Indians were manufactured with lefthand shifts, though it was still possible to switch back to classic Indian controls. Indians retained the oil tanks in the righthand gas tank long after other motorcycle companies began putting the oil tank under the seat. It was more difficult to make the gas tanks with a separate compartment for oil, but the surrounding gas and the positioning in the airflow kept the oil cooler in an Indian.

Although the Chief may be the standard Indian, it was not the only Indian. During much of the time the Chief was produced, Indian produced another big bike, the Indian Four. The Four was descended from the Ace Four and it was a bigger, slower, smoother machine than the Chief. The smaller Indian was the Scout, made in various engine sizes over the years. The standard Scout was mounted in a frame like that of the Chief, while a Sport Scout was entirely different with its stressed-engine frame and lighter weight. It was a successful competition machine for many years.

Indian history is sprinkled with racing success. The first motorcycle produced in this country was the original Indian Oscar Hedstrom made in May, 1901 to pace bicycle races. It was a pioneer with its all chain drive and concentric carburetor that enabled it to be so easily ridden. From that simple start Indian went on to set pages of speed records with single and twin cylinder engines. There were also as many firsts for Indian inventions as there were in competition, with Indian experimenting with swing arm rear suspension and four valves per cylinder very early on. The 1914 lOOOcc Electric Special even had an electric starter that operated as a generator to charge the batteries once the engine was running.

After a generation of producing some of the most innovative and competitive motorcycles in the world, Indian went through a succession of management changes that didn’t help the company or the engineering of the machines. Fortunately the basic designs in use had been well worked out and as Indian became less innovative, the motorcycles in production were not hurt. Good bikes remained good bikes.

That was the Chief. It gained the plunger rear suspension in 1940, a time when most other motorcycles were still hardtails. The suspension worked well to make a comfortable and good handling bike. When the Roadmaster telescopic forks were added in 1951 the front suspension became as good as the rear, and noticeably better than that on other big VTwins of the period. The Chief engine had been a better-than-average flathead design when it grew out of the Power Plus model. Its two cast iron cylinders are mounted at a 42° angle on the aluminum crankcase and topped by aluminum « heads. Flathead engine design provided for lots of swirl of the incoming mixture, but had limited compression, 6.5:1 being about the practical limit. On the Indian Chief there were two camshafts, one for the front cylinder and one for the rear cylinder, both gear driven on the righthand side of the engine. One cam operated both intake and exhaust valves through levertype roller followers. The length of the follower levers determined valve overlap, shorter followers being used on the Bonneville models for more peak power. A two-stage oil pump for the dry sump oiling system mounted on the outside of the cases on the righthand side and a particularly tidy primary case adorned the left side of the engine, enclosing a four row primary chain. Where the primary chain wrapped around the multiplate wet clutch, one row of teeth on the outside of the clutch was missing so a sprocket could be driven by the primary chain off the outside of the clutch. This sprocket drove the belt that drove the generator.

A magneto drive on the front of the engine remained on later Chiefs, even though a coil was mounted where the magneto used to go and a distributor was mounted above the timing case. The transmission bolted to the back of the engine and provided three widely spaced ratios, selected by the gearshift lever on the side of the gas tank.

The combination of controls on an Indian Chief are much different from what most of us are used to today, but this layout didn’t develop by accident. Indian had made a foot-shift, hand clutch motorcycle in the Twenties and certainly knew how to design the controls used today, but the controls on the Chief were what most riders wanted. They also work very well, once a rider is used to them. My brief ride on a Chief convinced me that a foot clutch wasn’t a bad system, just one that was unfamiliar. Riding around Fullerton behind Bob on his Chief was more educational. The giant buddy seat felt very much like the same style seat on a modern Electra Glide, the long travel springs supporting the seat allowing it to dive when the bike accelerates and lift on braking.

A sprung seat is a marvelous aid to comfort and this was even more important when the Chief was new and roads were generally rougher. Of course a sprung seat wouldn’t fit on most new motorcycles because they are so high that a rider on a sprung seat couldn’t touch the ground. On the Indian this wasn’t a problem. The front of the seat is narrow, so your legs reach straight down. The engine and center of the motorcycle are also narrow, so your knees fit together easily and comfortably. With a rider’s weight on the seat the seat height is much lower than that of modern Japanese motorcycles, even those with skimpily padded stepped seats.

While the sprung seat may make the most lasting impression after a ride on the Indian, the first impression I had was of the noise when Bob first brought the Chief to life. After priming the engine, he gave one lunge, which was answered by a raucous blast of slightly muffled explosions. That upswept exhaust pipe bending in around the rear fender didn’t reduce the exhaust sound so much as direct it to anyone misfortunate enough to have just been passed by the big, bellowing Indian. As inviting as the Chief looked, the sound was just a bit disturbing for the sheer power being emitted.

Aboard the big, springy seat my feet naturally fit onto the small metal tips at the back edge of the floorboards. These were installed for passenger footrests and there seemed to be enough room for even economy-size clodhoppers. Looking for a place to photograph the Chief, we rode through town, mostly in traffic. Obviously a machine as grand as the Chief gathers attention and respect, but it didn’t get much finger pointing or neck twisting. Keeping up with traffic was no problem. Just as it was in 1948, the Chief is a much faster machine than the cars on the road. Bob revved the engine more than I normally do taking off from a stop, but the combination of tall gearing and the treadle-type clutch made that normal procedure on the Indian. Give the bike a little gas, move the clutch back to where it just starts to take hold and the machine moves off, pulling the clutch into full engagement by itself.

Old motorcycles and old cars even more so did not have the greatest brakes, so it came as some surprise that the Indian could stop with apparent ease. When a car pulled out in front of us Bob merely stopped the Chief harder. The drum brakes on the cycle weren’t large, but they were more than adequate for the traffic of 1948 and well up to the task today.

At a stop Bob would push the clutch down, where it remained, there being no return spring on the clutch or the throttle. This made it easy to declutch well before the machine was halted and put either foot down without any difficulty. Shifting up through the gears took more time, the shifts being about as speedy as those of my three-speed Chevy pickup, and occurring at about the same speeds.

On an open stretch of gently curving road Bob requested that I hang on tight so he could demonstrate how well the motorcycle ran. I smugly smiled, held on lightly and waited briefly until he twisted the throttle what must have been two turns and the Indian Chief thundered away about as hard as any modern big bore bike with two people aboard. There was a real shot-from-guns feeling to the bike because it didn’t take any time for it to build engine speed or come up on cam. Power was related to throttle position, not engine speed. When he shifted to high gear at around 60 there was no relief from the thrust as I held on tighter and tighter. The sensation of acceleration must have been exaggerated because it just isn’t possible to force that much machine that fast with a 34-year-old flathead engine. It must have been my imagination.

Of course Bob Stark’s Chief is no ordinary 1948 Chief. In 1954 it was rebuilt to Bonneville 80 specifications, including the later model Roadmaster forks. In the 31 years Bob has owned the Chief it has had three top end jobs and one full rebuild, while accumulating 185,000 mi. Sharp eyed readers may note that the odometer doesn’t read 85,000, but then the odometer hasn’t been as durable as the engine.

In 1967 this same motorcycle was tested by Cycle World for a special Indian issue. At that time it turned a quarter mile in 15.8 sec. at a terminal speed of 84 mph. Those figures may not sound impressive to owners of current llOOcc motorcycles, but they were done with a machine weighing nearly 600 lb. It also has only three speeds in the transmission and shifts are gradual affairs on The Chief. For a little more excitement Bob has a 96 cu. in. Chief that’s filled with special preparation. When that motorcycle was used for drag racing it would regularly record trap speeds up to 117 mph, again with a three speed transmission and foot clutch. A 5.5 in. stroke and 3.25 in. bore don’t sound normal, but the results are outstanding.

The normal 80 inch Chief had a 3.25 in. bore and 4.81 in. stroke. Compression was 6.5:1 and normal redline is 5400 rpm. Performance modifications on a flathead engine run to installation of Bonneville cam followers, a longer stroke, lighter pistons and rods and the installation of the larger 1.5 in. Linkert carb to replace the 1.25 in. Linkert normally used on Indians.

Riding around on weaving hillside roads after taking the photos we didn’t discover the cornering limits of the Chief. Our pace was about the same as it would have been on any current touring bike and nothing was scraping. Occasionally we’d glide through a corner sharper and faster than I expected the Chief to handle and there were still no problems. The exhaust note was becoming more musical as we rode along, varying from the chuffing acceleration out of corners to the melodic percussion of cruising speed.

The Chief is at its best is away from traffic, where it doesn’t have to be shifted, but just exercised through its wonderful powerband in top gear. On country roads through rolling farmland it would be perfect. And when it was built more travel was done on rural, two-lane roads, there not being freeways crossing the country or quite as many people filling the cities.

For its time the Indian Chief was a magnificent motorcycle. It was a virtuous motorcycle in ways only an American machine can be, with its big, slow turning engine and concern for serviceability. The Indian is one of those now rare machines that draws the eye and entertains the mind with thoughts of how a machine can work. Everything on the Indian is intriguing, yet obvious. There is nothing on it that cannot be figured out by a normally mechanically inclined motorcyclist.

To a true believer like Bob Stark, Indian is a dormant motorcycle. It is an idea that still exists, if the production ended in 1953. Indian created a lot of good ideas, some of which are still available on another American V-Twin. But many of the sensations of the Indian Chief don’t exist any more, and that’s a shame. After a ride on an Indian Chief going back to the office on an llOOcc superbike just wasn’t as much fun. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue