THE SUNDAY MORNING RIDE

GEORGE MARTIN

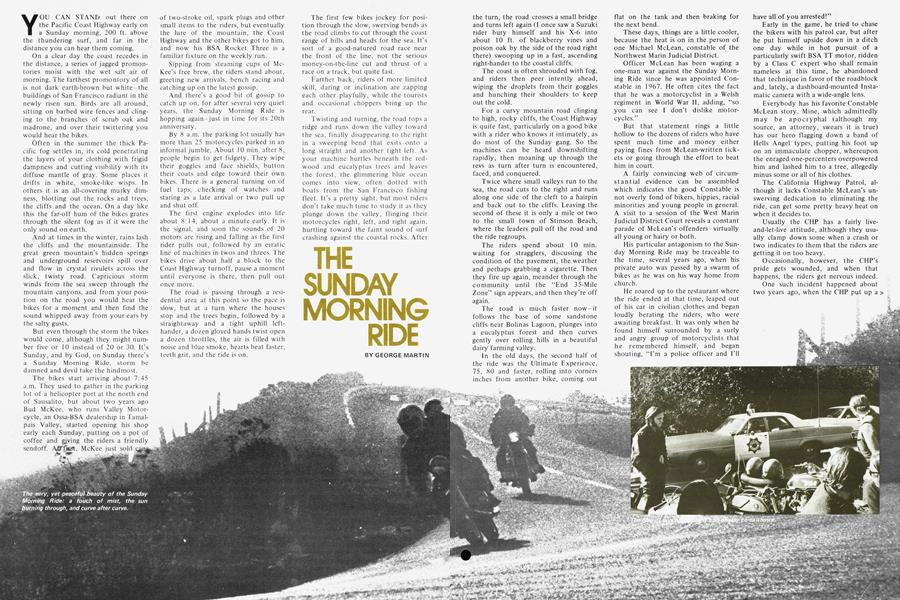

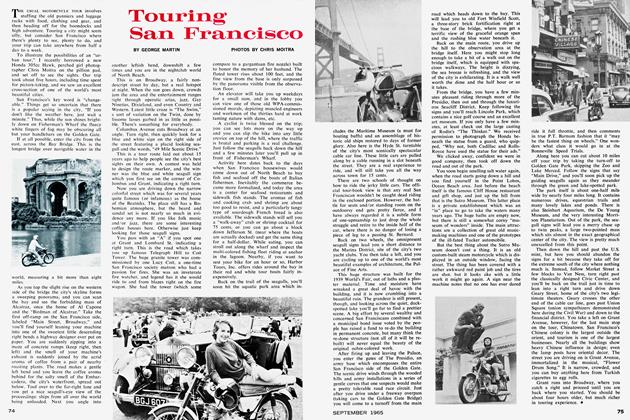

you CAN STAND out there on the Pacific Coast Highway early on a Sunday morning, 200 ft. above the thundering surf, and far in the distance you can hear them coming.

On a clear day the coast recedes in the distance, a series of jagged promontories moist with the wet salt air of morning. The farthest promontory of all is not dark earth-brown but white-the buildings of San Francisco radiant in the newly risen sun. Birds are all around, sitting on barbed wire fences and cling ing to the branches of scrub oak and madrone, and over their twittering you would hear the bikes.

Often in the summer the thick Pa cific fog settles in, its cold penetrating the layers of your clothing with frigid dampness and cutting visibility with its diffuse mantle of gray. Some places it drifts in white, smoke-like wisps. In others it is an all-covering murky dim ness, blotting out the rocks and trees, the cliffs and the ocean. On a day like this the far-off hum of the bikes grates through the silent fog as if it were the only sound on earth.

And at times in the winter, rains lash the cliffs and the mountainside. The great green mountain's hidden springs and underground reservoirs spill over and flow in crystal rivulets across the slick, twisty road. Capricious storm winds from the sea sweep through the mountain canyons, and from your posi tion on the road you would hear the bikes for a moment and then find the sound whipped away from your ears by the salty gusts.

But even through the storm the bikes would come, although they might num ber five or 10 instead of 20 or 30. It's Sunday, and by God, on Sunday there's a Sunday Morning Ride, storm be damned and devil take the hindmost.

The bikes start arriving about 7:45 a.m. They used to gather in the parking lot of a helicopter port at the north end of Sausalito, but about two years ago Bud McKee, who runs Valley Motor cycle, an Ossa-BSA dealership in Tamal pais Valley, started opening his shop early each Sunday, putting on a pot of coffee and ving the riders a friendly sendoff McKee just sold of two-stroke oil, spark plugs and other small items to the riders, but eventually the lure of the mountain, the Coast Highway and the other bikes got to him, and now his BSA Rocket Three is a familiar fixture on the weekly run.

Sipping from steaming cups of Mc Kee's free brew, the riders stand about, greeting new arrivals, bench racing and catching up on the latest gossip.

And there's a good bit of gossip to catch up on, for after several very quiet years, the Sunday Morning Ride is hopping again-just in time for its 20th anniversary.

By 8 a.m. the parking lot usually has more than 25 motorcycles parked in an informal jumble. About 10 mm. after 8, people begin to get fidgety. They wipe their goggles and face shields, button their coats and edge toward their own bikes. There is a general turning on of fuel taps, checking of watches and staring as a late arrival or two pull up and shut off.

The first engine explodes into life about 8:14, about a minute early. It is the signal, and soon the sounds of 20 motors are rising and falling as the first rider pulls out, followed by an erratic line of machines in twos and threes. The bikes drive about half a block to the Coast Highway turnoff, pause a moment until everyone is there, then pull out once more.

The road is passing through a resi dential area at this point so the pace is slow, but at a turn where the houses stop and the trees begin, followed by a straightaway and a tight uphill left hander, a dozen gloved hands twist open a dozen throttles, the air is filled with noise and blue smoke, hearts beat faster, teeth grit, and the ride is on.

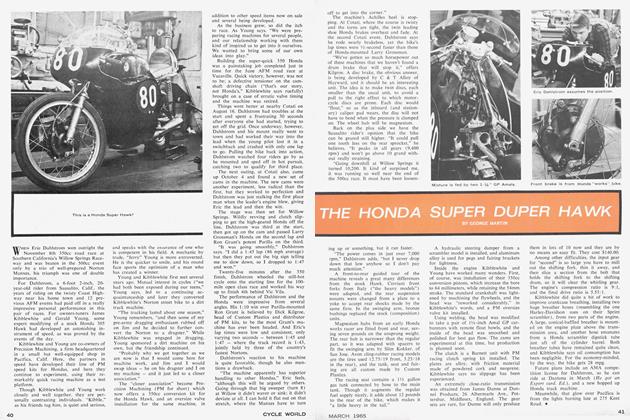

The first few bikes jockey for posi tion through the slow, swerving bends as the road climbs to cut through the coast range of hills and heads for the sea. It's sort of a good-natured road race near the front of the line, not the serious money-on-the-line cut and thrust of a race on a track, but quite fast.

Farther back, riders of more limited skill, daring or inclination are zapping each other playfully, while the tourists and occasional choppers bring up the rear.

Twisting and turning, the road tops a ridge and runs down the valley toward the sea, finally disappearing to the right in a sweeping bend that exits onto a long straight and another tight left. As your machine hurtles beneath the red wood and eucalyptus trees and leaves the forest, the glimmering blue ocean comes into view, often dotted with boats from the San Francisco fishing fleet. It's a pretty sight, but most riders don't take much time to study it as they plunge down the valley, flinging their motorcycles right, left, and right again, hurtling toward the faint sound of surf crashing against the coastal rocks. After the turn, the road crosses a small bridge and turns left again (I once saw a Suzuki rider bury himself and his X-6 into about 10 ft. of blackberry vines and poison oak by the side of the road right there) swooping up in a fast, ascending right-hander to the coastal cliffs.

The coast is often shrouded with fog, and riders then peer intently ahead, wiping the droplets from their goggles and hunching their shoulders to keep out the cold.

For a curvy mountain road clinging to high, rocky cliffs, the Coast Highway is quite fast, particularly on a good bike with a rider who knows it intimately, as do most of the Sunday gang. So the machines can be heard downshifting rapidly, then moaning up through the revs as turn after turn is encountered, faced, and conquered.

Twice where small valleys run to the sea, the road cuts to the right and runs along one side of the cleft to a hairpin and back out to the cliffs. Leaving the second of these it is only a mile or two to the small town of Stinson Beach, where the leaders pull off the road and the ride regroups.

The riders spend about 10 min. waiting for stragglers, discussing the condition of the pavement, the weather and perhaps grabbing a cigarette. Then they fire up again, meander through the community until the “End 35-Mile Zone” sign appears, and then they’re off again.

The road is much faster now-it follows the base of some sandstone cliffs near Bolinas Lagoon, plunges into a eucalyptus forest and then curves gently over rolling hills in a beautiful dairy farming valley.

In the old days, the second half of the ride was the Ultimate Experience, 75, 80 and faster, rolling into corners inches from another bike, coming out flat on the tank and then braking for the next bend.

These days, things are a little cooler, because the heat is on in the person of one Michael McLean, constable of the Northwest Marin Judicial District.

Officer McLean has been waging a one-man war against the Sunday Morning Ride since he was appointed Constable in 1967. He often cites the fact that he was a motorcyclist in a Welsh regiment in World War II, adding, “so you can see I don’t dislike motorcycles.”

But that statement rings a little hollow to the dozens of riders who have spent much time and money either paying fines from McLean-written tickets or going through the effort to beat him in court.

A fairly convincing web of circumstantial evidence can be assembled which indicates the good Constable is not overly fond of bikers, hippies, racial minorities and young people in general. A visit to a session of the West Marin Judicial District Court reveals a constant parade of McLean’s offenders-virtually all young or hairy or both.

His particular antagonism to the Sunday Morning Ride may be traceable to the time, several years ago, when his private auto was passed by a swarm of bikes as he was on his way home from church.

He roared up to the restaurant where the ride ended at that time, leaped out of his car in civilian clothes and began loudly berating the riders, who were awaiting breakfast. It was only when he found himself surrounded by a surly and angry group of motorcyclists that he remembered himself, and began shouting, “I’m a police officer and I’ll have all of you arrested!”

Early in the game, he tried to chase the bikers with his patrol car, but after he put himself upside down in a ditch one day while in hot pursuit of a particularly swift BSA TT motor, ridden by a Class C expert who shall remain nameless at this time, he abandoned that technique in favor of the roadblock and, lately, a dashboard-mounted Instamatic camera with a wide-angle lens.

Everybody has his favorite Constable McLean story. Mine, which admittedly may be apocryphal (although my source, an attorney, swears it is true) has our hero flagging down a band of Hells Angel types, putting his foot up on an immaculate chopper, whereupon the enraged one-percenters overpowered him and lashed him to a tree, allegedly minus some or all of his clothes.

The California Highway Patrol, although it lacks Constable McLean’s unswerving dedication to eliminating the ride, can get some pretty heavy heat on when it decides to.

Usually the CHP has a fairly liveand-let-live attitude, although they usually clamp down some when a crash or two indicates to them that the riders are getting it on too heavy.

Occasionally, however, the CHP’s pride gets wounded, and when that happens, the riders get nervous indeed.

One such incident happened about two years ago, when the CHP put up a routine roadblock at Stinson Beach.

A certain Kawasaki Mach III rider (who also shall remain nameless) slipped around the roadblock and headed off down the highway, pursued in short order by one of the state’s finest, aboard a mighty Harley 74. The officer was doing pretty good, they say, scraping floorboards and things in the corners, until he came to the infamous Schoolhouse Bend, a gentle left-hander with a suddenly decreasing radius “second comer” right in the middle of it and a deep ditch on the outside. The officer went tail over Duo-Glide into the ditch (it didn’t help that one of the riders who had been given a ticket at the roadblock happened along about then and started snapping pictures of the whole thing) and the riders knew the gauntlet was down.

The next week not a soul went on the ride. Another week went by and, figuring things were cool, the ride resumed. Every CHP car in the county was out there that morning, with a big roadblock set up, a hidden car to shut off the rear, and a helicopter hovering overhead. It was a great ambush, but, fortunately for the bikers, one of them crashed in the eucalyptus grove and everybody stopped to unbend his bike. Then the CHP rear-guard car came motoring along and the caper was blown.

The law enforcement establishment moved again last August, when the San Francisco Examiner published, in its Sunday magazine section, a long story about the ride. I hadn’t been on the ride in about five months when the story came out, but I figured something big would happen after all that publicity, so I greased up my Bultaco Metralla and showed up bright and early Sunday morning.

Sure enough, riders who hadn’t been around in years had gotten all nostalgic and decided to have one more go. Valley Motorcycle’s parking lot was overflowing--about 40 bikes scattered all around. When the run to the first turn started, the earth shook and the sky burned; it was quite a sight.

It was a gleeful group which talked and laughed at Stinson Beach, then got back on for the run north. Then, when they came around the last bend at Bolinas Lagoon, the long straightaway looked like a circus midway, with all the red lights going on top of the massed police vehicles. Some riders whipped around and headed south, but the CHP was there, too, with about 2 miles of Highway 1 sealed off and 40 motors in the middle.

The highway patrolman on the north side was in a pretty good mood that morning and only gave a couple of “muffler and lights” sort of citations, but the south side officers wrote about 15 “speed contest” tickets, a violation

which really covers drag racing and is almost impossible to prove in an open road situation, but which forces the “violator” to take time off from work to fight in court.

The run has ended at several different locations over the years (for a while it was a restaurant right across the road from the Constable’s house) but now it stops at the Inverness Coffee House, on the western shore of Tómales Bay, adjacent to the Point Reyes National Seashore. The restaurant has a nice covered patio, and unless the weather is very bad, the riders usually order breakfast, then step out and drink coffee and talk at the outside tables.

The restaurant owners are delighted at the heavy business on what would be a slow morning, and they have pots of steaming coffee at the ready and the grill pre-warmed. Ham, bacon, omelettes, steaming pancakes and melted butter are served up as the ride is re-hashed over hot coffee and the small incidents that make each Sunday different are recalled. Since Inverness is often just north of the fog belt, riders who had been riding nearly blind a few minutes before often find themselves sitting in the warm sun tossing bits of toast to chattering bluejays.

Although the Coast Highway has been popular with cyclists ever since there have been cyclists around, the Sunday Morning Ride as such originated with a young English Vincent enthusiast, Peter Adams, in the early 1950s.

“I lived in Mill Valley then,” Adams, now a field representative for Hap Jones Distributing Co., recalls, “and I had a good friend out in Inverness.”

On Sunday mornings, Adams would ride out to see his friend, and soon aS? small group of bike riding pals, mostly expatriate Britons, were joining on the run.

“We all used to hang out at the British-style pub in San Francisco,” Adams recalled a few years ago. “I sort of became the leader. It was a small, invitation-only sort of thing. In those days, an English-type cyclist was very rare. There was the big rowdy image problem, and most of the riders around had Harleys.”

Members of the group jokingly referred *o themselves as the Point Reyes Cafe Racer’s Society and turned out religiously each week on their BSA Gold Stars, Nortons and Vincents.

Not surprisingly, the machinery found on the ride is a sort of index of performance motorcycles. In the beginning, partly because most of the riders were British, and English machines were all that was available, save for the dread Harleys, the British machines had a near monopoly. But when the Honda invasion started in the early ’60s and the advantages of a lighter, better braked bike on a twisty road became apparent,

the Japanese bikes began a takeover which is now almost complete.

It was about 1960 that Adams stopped going on the ride. “I had a motorcycle shop of my own,” he said (he sold Hondas), “and I had less time off. Also I was afraid someone might get hurt and people would say, ‘Oh, that’s Pete Adams’ ride’.”

But if Adams stopped participating there were plenty of others who were happy to keep up what was becoming a tradition. And some of the original group meanwhile formally organized into the American Federation of Motorcyclists, San Francisco Chapter, and began racing for real at Northern California road courses.

Since the ride is an essentially nonstructured happening, a formal history is difficult to compile. But there are legends which are told and retold over another cup of coffee and which have become a sort of folklore of the ride.

There were the several times, each now legendary, when the unmuffled roar of racing Manx Nortons were heard along the highway. Pete Adams took his along at least once, and one Bob Knott, now a porpoise trainer at Marine World, had the dubious honor of putting his Manx under the front bumper of a Chrysler one foggy morning.

And since we’re on exotic motorcycles, there’s a chap who occasionally arrives on a full dress Harley 74 and really gets it on, trailing showers of sparks as he scrapes off bits of his underside on the corners.

Then there is the farmer whose pasture gate was right at the end of a long straight with an abrupt left turn. After his gate was destroyed a couple of times by riders using his “slip road” he began opening the gate each Saturday night and closing it again Sunday noon.

I am probably the only rider on the run who ever put his bike literally into the fork of a tree. It was a rainy morning, and I had spent the previous day talking to an Englishman who told me over and over about how fast you could go in the rain if you tried. I didn’t see how the Bultaco got into the tree because I was too busy sliding under a barbed wire fence and off a cliff into a creek, but when the other riders pulled me out, one friend said, “When I came around the corner and saw that motor in the tree, I thought, “Oh, God, what am 1 going to tell his wife?”

Several riders have missed one of the many corners just past Stinson Beach and put various types of motorcycles various distances out into the mtjft and/or water, depending on the tide. One poor chap missed the turnoff to Inverness several years agö, sped, through a yard and off into 8 ft. of water in a canal at the foot of Cornales Bay. ^

That story didn’t end until aft«' breakfast, when he and some friends got a line onto the bike and finally hauled it out, much to the delight of the two little old ladies who lived in the house.

Occasionally, a photographer will station himself along the road to take photographs of the speeding bikes. About a year ago one did this at the little town of Olema, where a downhill road curves into the Coast Highway from the right. The turn is banked and the highway rises over the banking, making a large hump in the road.

This particular morning a chap named Jerry came zooming up to this spot, saw the photographer, and decided to give him a great picture.

“I could see there was one coming,” he said later, “so I just tucked it in fourth and went sailing about 20 ft. like a TT rider.”

It wasn’t until Jerry’s Yamaha 180 was airborne that he noticed the three squad cars and two police bikes parked by the side of the road.

“The cop was pretty decent about it,” Jerry said later. “I asked him why they didn’t just put the heat on until no one would come on the ride anymore, and he said, ‘Well, you guys are out here pretty early in the morning, and as long as we don’t get too many complaints we don’t want to kill it.’ ”

Which all the riders thought was an extremely sensible attitude, and many cups of coffee were raised in friendly toast to that patrolman that day.