THE EMERALD TOUR

Ireland on Five Gallons a Day

PETER EGAN

IRELAND. The name provoked all kinds of response in England. You'd sit in a bar in Birmingham and the man who'd just bought you a pint would say, “Well, where are you two adventurers riding next?” You’d answer “Ireland,” and a strange hush would fall over the pub. A few people would shake their heads, the bartender would raise one eyebrow, and your drinking friend would equivocate, “Well. . .that might be a nice trip. I guess. But I don’t mind telling you I wouldn’t go there myself.”

“Ever been there?”

“Nope.” The answer always came with stunning quickness, like the standard medical questionnaire response: “Any mental illness in the family?” “Nope.” Ever been to Ireland?” “Nope.”

A friend in Liverpool reacted the same way. So we asked, “Aren’t you curious about a big island right next to your own?”

“Nope. Never been there. You see . . . (a how-shall-I-phrase-this pause) it might be very well for you Americans, but if I walked into an Irish pub or hotel with my English accent, I can’t say how I’d be treated. I'd be on edge all the while.”

Others told us, Americans or not, to stay away. A crazy, dangerous place of no consequence. Trouble. Don’t go to Ireland. Tour England.

“We’ve already toured England. Twice.”

“Tour it again, mate.”

I learned a long time ago to take this kind of advice with a large grain of salt. I'd been warned by Frenchmen to avoid Italy like the plague, by northerners not to ride through the Deep South, by mature adults to stay off motorcycles, by country folk not to walk around New York City, by all kinds of people not to fly airplanes, and by clergymen to stay away from girls in high school. I eventually learned that these advisors had two things in common: First, they had almost no experience with the thing they mistrusted; and second, they were always dead wrong.

There was, no doubt, trouble to be found if you went looking for it in certain select industrial neighborhoods of Belfast in Northern Ireland, but our plan was to tour the south of Ireland, reputedly peaceful since it became a republic in 1922. We had a motorcycle, a few hundred dollars, and exactly one week of remaining summer vacation.

We left from Liverpool on a Saturday evening, following a line of cars up a steel ramp into the gaping maw of the Connought. our ship to Dublin. Cars were packed bumper-tobumper in orderly lines, but a loading foreman directed our bike to one side and pointed to a thick coil of rope on the deck. “Take that,” he said, “and lash your motorbike to the rail against the hull, in case the sea gets rough.” Our motorbike on this trip was a shaft-drive Suzuki GS650G, kindly lent to us by our English friend Ray Battersby, who works for Suzuki U.K. and lives near London. We tied the bike down, padding the tank with gloves and scarves so it wouldn’t scrape on the hull, and climbed onto the main deck.

There was no danger of rough seas. The ocean was mirror-like as we sailed out of Liverpool and into the Irish sea, with moonlight shining through the scattered clouds. Traveling on the cheap, as usual, we hadn't paid the extra money for a stateroom, so we spent the night alternately sipping coffee at the snack bar, trying to nap in the reclining chairs on the enclosed foredeck, and looking at maps of Ireland. We pronounced the names of counties aloud, just because they sounded good: Wicklow, Wexford, Waterford and Cork; Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary, Clare and Galway. And then there were the Boggeragh Mountains, the Slieve Bloom Mountains, Blarney, Dingle Bay and the River Shannon. The whole island looked like a Tolkien invention, full of impossible, imaginary names and places.

Barb spotted Ireland first, just before dawn. She pointed out what I believed to be just another low bank of clouds, but it emerged as a lower, greener cloud lying in the early morning mist. Our ship steamed into Dublin Harbor and, after much roaring and reversing of the props, bumped solidly against the dock, as if to prove the island was solid and not just a hazy green vision in the Irish Sea. The ramp dropped and after a quick customs check we accelerated out into Dublin’s streets, which were just waking up for Sunday church.

Greater Dublin, we discovered, sprawls over a large area, but its downtown is condensed into a pleasantly small area around the River Liffey. The city has an old, stately feel about it, with very few tall buildings and a lot of Georgian architecture. The houses of Dublin are famous for their neatly painted doors and window casings, contrasting with the gray stone and brass trim. We rode around the largely empty streets for about half an hour, exploring and waiting for the restaurants to open. “I wonder,” I said to Barb at a stoplight on O’Connell Street, “if there’s anywhere around here you can get two semi-fried eggs, two undercooked sausages, two slices of boiled tomato and a cup of truly terrible coffee.”

“This is Ireland,” Barb reminded me, “not England.”

“I forgot. I wonder if they have the same breakfasts in Ireland?”

We camped at the door of a café whose sign promised the place would open soon, and met a young American couple named Steve and Kathy, who were also waiting at the door. We all went in and had the Breakfast Special: two semi-fried eggs, two undercooked sausages, two slices of boiled tomato and a cup of truly terrible coffee.

Steve and Kathy gave us the phone number of a good bed & breakfast place where they’d stayed and suggested we call after breakfast. “Ask for Mrs. O'Donovan,” Steve said.

Mr. O’Donovan answered the phone. “Ah, then,” he said, “so it’s a room you need. You’ll be wanting to talk to my dear wife, then. She’s just now returned from mass with our two young boys.”

I held the phone and smiled to myself. In America, the man would have said, “Just a minute,” and left it at that. In Ireland, people painted you small pictures with words, always in a soft, quicksilver cadence that was easy on the ears.

We found the address on a quiet residential street a few miles away, and Mrs. O’Donovan turned out to be a tall, sparkling woman with a beautifully kept house. She was not at all put off by our Belstaff suits, boots and motorcycle gear, but seemed genuinely intrigued that a married couple would be traveling in this fashion. “Cold and damp, I should think,” she said, bringing us hot tea.

I'd heard motorcycle touring in the British Isles described before, but never quite so succinctly.

After cleaning up and unpacking our luggage, Barb and I rode the much-lightened Suzuki back into the city center, where we ran smack into the annual Children’s Day Parade pouring through the middle of Dublin. There were marching bands, soccer clubs, dance troupes, drill teams, etc., all children, marching to the scattered applause and flash photography of their parents. The older kids were confident and showy; the younger ones still wide-eyed and wary, wondering what kind of civilization they’d been born into that marched them down the street dressed like little pumpkins and leprechauns and drum majorettes.

We stopped in a pub for a glass of Guinness, and a man at the bar looked out the window and said it wasn’t a very good parade. “They do it much better in Texas,” he declared, “for the football games. Irish never learn to handle the baton properly as Texas children do. Look at them, dropping the things all over the street.” I thought they looked just like the kids from my own grade school, but I'm not from Texas, either.

Barb and I later wondered over to McDaid’s Pub. McDaid's is reputed to be the erstwhile hangout of writer and poet Brendan Behan, who supposedly drank there as a young dog. There was a picture of him on the wall, and a collection of students, professors, scarved hangers-on and other rowdy drinking-and-smoking classes at the bar. We discovered that first night that you have to be careful in Irish pubs because genuine draft Guinness is so easy to drink. Guinness Stout, if you're not already a convert, is a very heavy beer—like brew that has the taste of dark roasted malt with overtones of molasses and licorice and has a color that is closer to black than brown. A friend of mine who hates the stuff says it tastes like burnt wool athletic socks from someone’s gym locker, but I've grown quite fond of it. Guinness is the official pub drink of Ireland and is also widely drunk in England, commonly mixed half-and-half with lighter beers and ales. Great stuff, as they say, but it certainly doesn’t help you climb stairs.

In the morning. Barb and I packed our luggage, which consisted of a tank bag and two soft saddlebags, and said goodbye to the O'Donovans. On our way out of Dublin we stopped to see the famous Book of Kells, housed in the Long Room of the Trinity Library. The book is a richly illustrated manuscript of the four Gospels, believed to have been written around the year 800 A.D. in a monastery scriptorium. A woman ahead of me in line peered through the glass at the elaborate Insular Celtic script, intertwined with snakes and tendrils and flowers, and said in a New York accent. “I wundah what it says?”

Her husband snapped back, “How should I know?”

I supressed an urge to read it for them and make it up as I went along: “Gloria entered the room, flushed from her tennis lesson . . . .”

We went south first, along the east coast of Ireland, through Bray, Graystones, Newcastle and Wicklow. It took some time to get out of greater Dublin, but once we were free, the two-lane road down the coast was wild and beautiful, sweeping down into one harbor after another and back over the cliffs. The weather was cool and overcast with the sun breaking through thin spots in the clouds occasionally, instantly changing the color of the ocean and the green fields. We stopped for lunch at a little town called Gorey. Lunch, the big meal of the day, consisted of roast pork, potatoes, peas, cabbage, tea and strawberries with cream. There's nothing terribly subtle about the restaurant food in Ireland, but it’s good and you get a lot of it.

Near Wexford we filled up our gas tank for the first time. Gasoline in Ireland costs about 1.55 Irish pounds (or Punts, as they are properly called) per Imperial gallon. Only a few years ago, when the Irish pound was worth around $2.20, this was expensive fuel, but now that the pound is approaching parity with the dollar, Irish gasoline is becoming something of a bargain for Americans, if not for the Irish themselves.

There are no motorways or expressways to speak of in Ireland, so there is a fair amount of commercial traffic on the main roads along the coast and between larger cities. Leave the main roads, however, and the traffic drops off' to a desultory mixture of sheep, tractors, the occasional car. cattle, donkey carts and pedestrians, all traveling at roughly the same speed and spaced well apart. Irish drivers tend to be relaxed and easy going, with none of the murderous seriousness you find on the Continent. There is a sense of good-natured flexibility and complete patience. Making time on Irish roads is not in the cards, however, and dragging your knee in corners isn't recommended unless you wish to become One with the back of a haywagon, or are especially fond of sheep.

We stopped for the night at Waterford and found a bed & breakfast place overlooking a small square, had dinner nearby, went to a local theater for a well-acted production of Stagestruck at the Royal Theater, and then wandered around town, exploring at random.

We came across an Egan's Pub and, naturally, dropped in for a pint. The Egans of my own family, were supposed to have migrated to the U.S. from Waterford during the great potato famine. I have to admit that I’ve always been a little bit skeptical of the Roots Movement, since most of the people I know who are overly concerned with the accomplishments of their forebears seem not to be up to much of anything themselves. Still, it’s fascinating to wander the streets of a foreign town and imagine your great grandparents walking down to the docks and sailing off to a new life in America. My own relatives ended up in Minnesota, apparently because Ireland wasn’t cold enough for them, or had too few mosquitoes.

Waterford, like many of the cities we rode through, is laced with ancient walls, fragments of towers, bits of old monasteries and other ruins. Old stone structures that would be national landmarks in the U.S. are so common in Ireland that no one pays them much mind, and they are often integrated into lesser but more modern buildings. The ruins of a 13th Century guard tower become the north wall of a tin-roofed auto repair shop; part of a medieval city wall is used as one side of a pink stucco beauty parlor, and so on. It’s an odd mixture of the old and the new, the elegant and the garish.

On the way back to our room in the evening we stopped to talk to an old woman who was leaning out the front window of her small house. “It’s good to see a young man and wife walking together,’’ she said. “Now that the pubs serve food and allow women inside, there’s no reason a’tall for a man to come home to his family any more ....’’

If she thinks it’s bad now, I thought, wait’ll they discover Space Invaders.

In the morning we rode out to the Waterford Crystal factory at the edge of the city and watched the glassblowers and cutters at work. I’d never seen such a cheerful, good-natured bunch of workers in any factory, but then, the last factory I worked at was a gunpowder plant, where anxiety was our most important product. Barb and I bought a crystal salt-andpepper-shaker set, after voting them most likely to succeed in a tank bag. Wine glasses and chandeliers were out of the question.

We rode south through Dungarvan and Cork along the coast and then inland to Killarney. Killarney has a large tourist trade because it’s the jumping-off point fora beautiful loop of roads around the mountainous Kerry Peninsula. The route is called the Ring of Kerry. We found a nice old hotel in Killarney, and after dinner went looking for some authentic Irish folk music. “This is a big tourist town,’’ I told Barb. “They’ve got to have a good club somewhere.’’

We found a pub with a big sign that said Live Music Tonight and sat down inside with a drink. A band showed up—four guys in cowboy shirts and bandanas—proceeded to set up their equipment and then launched into a half-hour of Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson tunes. “Not exactly the Boys of the Lough or the Sands Family, are they?’’ I said to Barb over the thumping Fender bass and the whining steel guitar. When we left, they were singing “Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys’’ in perfect Texas twang.

In the morning we rode south along the forested shore of Lake Leane, in the first real sunlight of the trip. When we came to open meadow and mountain country near the coast, we stopped on a hilltop to look over the landscape. If Paris, as Henry Miller said, is composed of a hundred different shades of gray, then Ireland has at least as many shades of green; grass green, moss green, tree green, meadow green, etc. When the sun comes out from behind a cloud, the effect is stunning, like the switch from black-and-white film to color in the Wizard of Oz. There’s a shifting, moody quality to the light, and the sky seems to move over the island at a faster-than-normal pace.

Part way down the Kerry Peninsula we decided to get away from the tour buses and turned inland on a narrow road that wound through a mountain range with the strange name of the Maggillycuddy’s Reeks. This almost empty road took us through a rugged landscape of rocky valleys, sheep farms, peat bogs, abandoned houses, cemeteries filled with Celtic crosses, old stone churches, walls and the ruins of walls. We came to several Ys in the road and made our choices at random. The scenery and the road were so perfect for motorcycling, we really didn’t care where we were going.

Until late in the afternoon. We suddenly decided it was time to start wending our way back to civilization or we’d be sleeping on the moors; just us, the Suzuki with its empty gas tank, and whatever it is that howls on the moors at night.

Luckily, you’re never far from friendly advice, even in the remotest parts of Ireland. In the countryside everywhere there is a class of individual we came to call The Solitary Walking Man. You see them miles from anywhere, walking along the roads in neat caps, ties and jackets,> walking with canes, walking with hands behind their backs or strolling along smoking pipes. A sociologist would probably tell us this phenomenon is economic—the cost of fuel, the cost of cars, etc. Personally, I’d like to think that most of the people walk from one place to another because the country is so lovely that a ride is simply a missed opportunity.

We were pointed toward the coast by an old gentleman in tweeds who was walking with his sheepdog. By nightfall we'd found a nice bed & breakfast place in the little town of Tarbert, at the mouth of the River Shannon. When we signed the guest register, the landlady looked at what I had written and said, “Ah, you're American. I thought you were English. You have English registration on your motorbike.” I looked back at the bike and wondered how many other people had made that same mistake. Probably quite a few, but no one, on the highways or elsewhere, had shown us anything but courtesy and hospitality. In some places I could think of. just being a motorcyclist would have lowered the level of warmth and charm. This lady had cheerfully showed us a room, thinking we were English motorcyclists.

There is a saying in Ireland that if you don’t like the weather, just wait a minute. Generally that’s true, but sometimes the weather takes more than a minute to change. Sometimes it can take several hours. And if it’s gusXiwg, a. cold, driving, rain off the North Sea and you're on a motorcycle, it can take days. We rode toward Galway on a couple of those days.

Barb and I were both wearing Belstaff jackets of the black, waxedcotton variety, with matching Belstaff pants. They worked great in those famous one-minute Irish showers, but in a steady, lashing rainstorm they began to wick moisture through the inner lining, and by the time we reached Limerick we were so wet we didn’t care any more. In an effort to close the barn door after the horse got drenched, we stopped at a Limerick sporting goods store and bought the closest thing we could find to Dry Rider suits—a couple of rubberized canvas duck-hunting outfits, olive drab in color.

Slightly warmer, we rode through some of the prettiest scenery on the trip—thatched cottages, the towering cliffs of Moher, endless castle ruins, etc., —all glimpsed through faceshields streaming with water and fogged from within. It just wasn’t a motorcycle day. We sloshed our way into Galway late in the afternoon and took a room at the first structure with a Hotel sign on the wall.

Our hotel turned out to be, essentially, an old men’s rooming house with a few extra rooms, the kind where the wallpaper, carpets and paint were all finalists in some longforgotten eyesore contest. We draped our wet jackets and riding gear around the room to dry and went down the hall for a hot bath. The hot water was cold, so the hotel clerk said to wait an hour and it would be warmer, which we did, but it wasn't.

The heating of water seems to be something of a black art in most parts of the world I’ve visited, except for Switzerland, Germany, Japan and the U.S. The English and the Irish manage to get it sort of hot at certain hours of the day if you give them plenty of notice, while the French succeed in heating water only in coffee makers. Spaniards (as nearly as we could tell during the month we spent touring the Iberian hinterlands) are not aware of any process by which potential bath water can be heated. I've often thought that some benevolent American plumbing magnate should send a missionary to Europe with a cutaway water heater and a pointer, just to pass this technology along and get the ball r olling.

Ireland is a country of not much heat, but plenty of warm blankets, so our pneumonia was relatively mild the next morning and had not spread to both lungs. We poked around Galway, then had lunch at a pub. sharing a table with two old retired farmers. One had no teeth or hair, aind the other had one eye, a badly scarred lip and a bandaged hand with yel low iodine stains around his fingers and wrist. We bought each other a couple of drinks and then settled down to a potato, cabbage and bacon me al.

“So you're American.” the oneeyed man said, dropping some food on his lap and deftly returning it to his plate with the side of a butter knife. “Did you know that John Wayne once came to Galway and had his famous fistfight with Victor McLaglen right here, and that John Ford came in this very pub when he was filming a famous American movie called The Quiet Man?" I confessed we hadn't known. “Aye,” he said, “I saw them all, and I’ve been to America myself to visit my brot her in Baltimore.” He dropped some food and searched for it with his good eye. but the food had fallen out of range. “The Americans ask for a lot,” he continued, “but they give you a lot when you go there.”

“Ah well.” said the bald one agreeably, “They work hard and save their money and deserve a good time.” When we’d left the pub. I said to Barb, “There are times when this country makes me feel like Jim Hawkins in Treasure Island. At least one of those guys should have had a parrot on his shoulder.”

It was almost time for us to go back to working hard and saving for a good time, so we had to turn away from the coast and the stark beauty of Galway to head back toward Dublin. Central Ireland, south of Lough Ree and through Westmeath, is gently rolling country with relatively straight roads, so we made good time.

Regardless of the roads, however, speeding across the countryside is difficult, and I told Barb that the Tourist Bureau should issue horse blinders to travelers who have to follow a schedule, especially if they own cameras. That’s the tragedy of traveling in Ireland with a camera: You could stop anywhere in the country and shoot up a roll of film while turning on your heel in a 360-degree arc. You are surrounded everywhere with achingly beautiful scenery, ancient buildings, interesting people and whatnot. You just have to shrug it off and breeze by castles, ruins, churches and char -ming villages without a second look. There just isn't time to investigate everything.

One thing we did stop to investigate, however, was a pub in the little town of Moate, which had a sign that said “P. Egan” over the door. We went in, and the owner, a quiet, friendly man in his forties, introduced himself as Peter Egan. “That’s my name, too,” I said. We bought each other drinks, and he gave me a handful of Guinness labels with our mutual name printed at the bottom. “These are left over from the days when we used to bottle our own stout for customers,” he said. I gave him a couple of Cycle World business cards with the same name on them, and then we said goodbye.

We rode hard for the rest of the afternoon, looking neither to the left nor to the right, averting our eyes from the scenery. We had a boat to catch in the morning and could not be distracted. The Suzuki had run so flawlessly and needed so little maintenance (i.e. none) in our one week of touring that I’d stopped expecting anything else. It occured to me on that last stretch of road that a 650 was almost exactly the right size for a twoup tour in a country the size of Ireland, and possibly at the upper limit of necessity. The narrow, winding roads, the mixture of rural traffic and animal life, not to mention the frequent need to stop, park and explore, made maneuverability far more useful than huge reserves of acceleration and horsepower. Speeding through Ireland made about as much sense as rushing through a good dinner or a close friendship.

We made it to Dublin late in the afternoon and checked into a bed & breakfast place on the north side of the city. We cleaned up, put on our last change of clean clothes and rode out to a peninsula named Howthh Haad. We found a famous old place called the Abbey Tavern, had a wonderful salmon dinner, and stayed to hear the Abbey singers do Irish ballads and folk songs. After a couple of Irish coffees we rode back to the bed & breakfast late in the evening. In the morning we had a breakfast of two semi-cooked eggs, two undercooked sausages, two slices of boiled tomato and a cup of truly terrible coffee.

“From dust we came . . .,” I said to Barb.

“I’m beginning to like these breakfasts,” she said.

“So am I. Time go go home.”

Our departure from the island was like a movie played backward. We tied our bike down in the ship’s hold again and went up on the deck to watch Ireland move east on the horizon. Perhaps 10 miles out, the land became that same low, green shape on the water, and in another five miles the clouds and mist had swallowed it up. I stood on the deck for a long time, watching seagulls and the wake of the boat, and thinking what a pitifully short time one week was to spend in a place like Ireland.

A motorcycle is almost always one of the best ways to see a country as it should be seen and to get under the surface. And yet, in leaving Ireland, I almost felt as though we’d seen it from the train. It was too complex, an island of too much depth and too many layers. It was a place that demanded a summer of our time, at least, and maybe a slower motorcycle. Or one that broke down a lot.

As our boat approached the coast of England late in the afternoon, I thought about all the well-meaning people who had advised us not to go to Ireland, and I wondered if they were related, in some spiritual sense, to the same people who warned us never to ride a motorcycle. EB

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

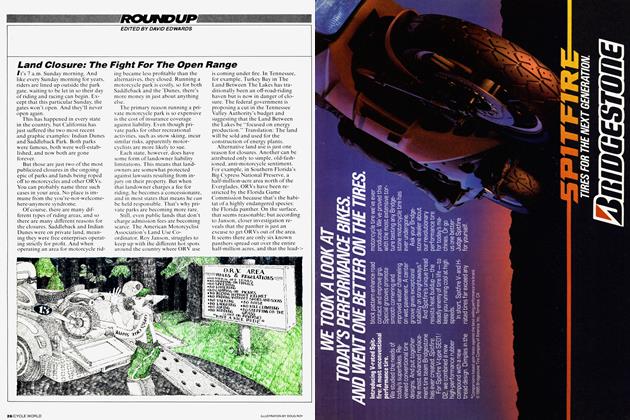

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985