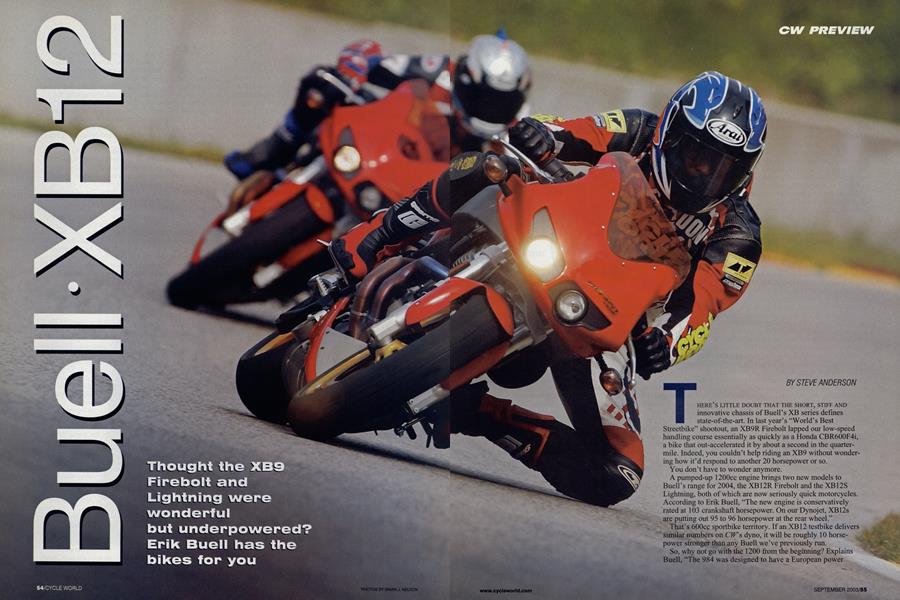

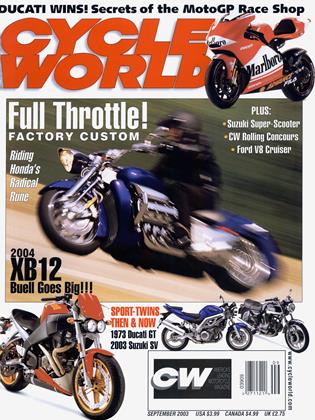

Buell · XB12

Thought the XB9 Firebolt and Lightning were wonderful but underpowered? Erik Buell has the bikes for you

CW PREVIEW

STEVE ANDERSON

THERE'S LITTLE DOUBT THAT THE SHORT, STIFF AND innovative chassis of Buell's XB series defines state-of-the-art. In last year's "World's Best Streetbike" shootout, an XB9R Firebolt lapped our low-speed handling course essentially as quickly as a Honda CBR600F4i, a bike that out-accelerated it by about a second in the quartermile. Indeed, you couldn't help riding an XB9 without wondering how it'd respond to another 20 horsepower or so.

You don’t have to wonder anymore.

A pumped-up 1200cc engine brings two new models to Buell’s range for 2004, the XB12R Firebolt and the XB12S Lightning, both of which are now seriously quick motorcycles. According to Erik Buell, “The new engine is conservatively rated at 103 crankshaft horsepower. On our Dynojet, XB12s are putting out 95 to 96 horsepower at the rear wheel.”

That’s 600cc sportbike territory. If an XB12 testbike delivers similar numbers on CWs dyno, it will be roughly 10 horsepower stronger than any Buell we’ve previously run.

So, why not go with the 1200 from the beginning? Explains Buell, “The 984 was designed to have a European power characteristic, to be more rewy. The 1200 is a big torque motor. They are two different engines with very different

Buell XB12

characters but with as many common parts as possible.” Accordingly, the XB9 models remain in the lineup, and will benefit from a price reduction that separates them further from the $10,995 12s.

The 1200 is essentially a long-stroke version of the 984, reverting to the 3.8-inch stroke of older Buells and Harley 1200 Sportsters. It shares the 3.5-inch bore, cases, cylinder heads, valves, ports, valve springs, camshafts and most other parts with the 984. But there are significant differences. New pis tons keep the compression ratio to 10:1 with the same tight combustion chamber as the 9, and new, shorter-than-984 connecting rods shed vital ounces from the old 1200 rods while maintaining a common deck height and actually offering improved strength. A reduction in primary ratio to 1.5:1 from 1.68:1 drops engine speed on the road in any given gear, while both 984 and 1200 share a new common final drive, an all-new Goodyear belt-but more on that later. Rubber vibration isolators are re-tuned specifically for the vibe characteristics of the 1200.

But the big changes are on the intake and exhaust sides. The new 1200s breathe through a big 49mm throttle body (45 mm on the 984) and squirt gas through new injectors. According to Tim Osterberg, one of the engineering leads of the XB12 project, “In going after the Euro2 emission standard without a catalyst, the injectors were critical. We have two different injectors, both shorter than the 984 part, with different spray patterns, the intent being to get all the fuel on the intake valve head. The geometry of the port is great for flow, but makes it hard to target the injector. When you hit the valve-the hot spot-fuel atomizes better. You win with both better drivability and better emissions.”

Erik Buell continues, “For a pushrod, air-cooled, two-valve design, this is an awesome engine. Great BMEP (brake mean effective pressure, a measure of efficiency in power production), good BSFC (brake specific fuel consumption), great

emission numbers, great power. The EPA fuel-economy numbers are almost as good as the 984’s-48 mpg city/65 mpg highway-and it just marginally misses California 2008 emissions without a catalyst.” He laughs, “Tell your wife it’s a great commuter bike with great mileage and great emissions.”

The phenomenal spread of power of the new engine-it makes 63 foot-pounds of torque at 2000 rpm, 68 at 2500 and doesn’t fall below 70 from 4000 to 6800 rpm-can be directly attributed to an active, dual-path muffler, a device that goes far beyond Yamaha’s EXUP system in providing tunability. Previously, Buell engineers were confronted with choosing between excellent top-end power with a big hole in the lower midrange, or a broader powerband with less peak power. This time, they wanted it all. To get it they added the dual-path muffler, which has a large butterfly valve inside encased in an expensive stainless-steel investment casting for reliability. A stepper motor resides under the “gas tank,” resting in foam on a new airbox cover. (The airbox lost less than a liter in capacity). The stepper motor pulls on a cable that opens and closes the valve in less than a half-second. Reading throttle position and rpm, the 12’s black box tells the stepper motor to open the valve below 3350 rpm, and above 5100 rpm when throttle opening is 70 percent or greater. In the midrange and at low throttle settings, when a little more backpressure actually improves power, the valve is closed. Dyno curves with the system working and not show that it fills in a huge midrange hole. And the stepper motor is quick enough to be effective even when accelerating in the brief couple of seconds through first gear, because the effect of the valve opening is very non-linear. Even cracking it 10 percent open as you charge above 5100 rpm in first gives you more top-end power. The only costs of the active muffler were in dollars and weight; the heavier muffler, the cable and the stepper motor add about 10 pounds to the XB12s.

The XB12 project also continues a drive to end any concern about the reliability of Buell motorcycles. The older tube-frame Buells had their problems and were subject to a number of recalls. But Tony Stefanelli, the engineer in charge of all XB-series Buells, claims that, “In Buell’s latest test duty cycle, the bikes get ridden very hard-far beyond any normal street riding-for thousands and thousands of miles. We’ve run competitive product on that test, and they haven’t been as durable as our bikes. We learned a lot by running other

products. We’ve set a mark, and we’re trying to have the best durability of any motorcycle manufacturer on the planet. The public perception of Buell is going to be changing with the XB product line as the bikes get miles on them.”

Some of the changes to all XBs reflect those concerns. Both 9s and 12s for 2004 get a new Goodyear final drive belt, the first non-Gates belt to appear on any product associated with Harley-Davidson. According to Erik Buell, “The Goodyear final drive has changed our service interval from 15,000 to 25,000 miles. That’s a very conservative prediction of our service life from the belt; we have total confidence in that prediction, and maybe they have more durability beyond that-we’re still testing them.”

The new belt is more flexible and more able to handle debris damage and mishandling in service-most recent Buell belt failures have been traced to mechanics or owners not following recommended procedure on rear-wheel removal and refitment. The new belt will survive having a hole punched in it by a trapped stone and still transmit power; Buell describes such a damaged belt as providing a “limp-home mode.” The much-improved durability allowed removal of the extensive belt guards of last year’s 9s, reducing unsprung weight, improving serviceability and providing a cleaner look. In addition, Buell and Stefanelli mention

and Stefanelli mention how actively the company is pursuing any problems reported. A warranty-review team, comprising Stefanelli and other functional group leaders in the company, meets once a week to review what’s happening out in the field. Each warranty item is investigated until the cause is understood. “Every single issue gets looked at,” says Stefanelli, whose goal is to, “move us down to zero warranty claims.” Doubling all Buells’ warranty periods to two years/unlimited miles is a mark of the company’s newfound confidence in its products. Aiding the cause, the new engine is protected from user

abuse by its controlling black box. The yellow zone on the new engine starts at 6400 rpm, while the red zone starts at 6800. In first through fourth gears, the black box dials in a “soft skip” (one engine/injection non-fire every four cycles) at 6400 to 6800 after 3 seconds of smooth running. A “hard skip” (one non-fire every other cycle) is initiated after 5 seconds. Why? The 3-second smooth-running range allows the yellow zone to be used for acceleration, but doesn’t allow you to live there, while the soft skip gives you a gentle warning that it’s time to shift. Buell is shooting for very high durability targets (think 100,000 miles) and extended running at 6800 rpm shortens big-end bearing life more than considered acceptable. So the black box enforces the warnings on the tach.

In the end, the new Buell 12s promise: 1) to be the most powerful Buells ever; 2) to have the broadest powerband; and 3) to be the most reliable. That should make their $ 1000 price increase over last year’s XB9s a bargain, and make the 2004 XB12 Firebolts and Lightnings the best sportbikes ever offered by an American manufacturer. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue