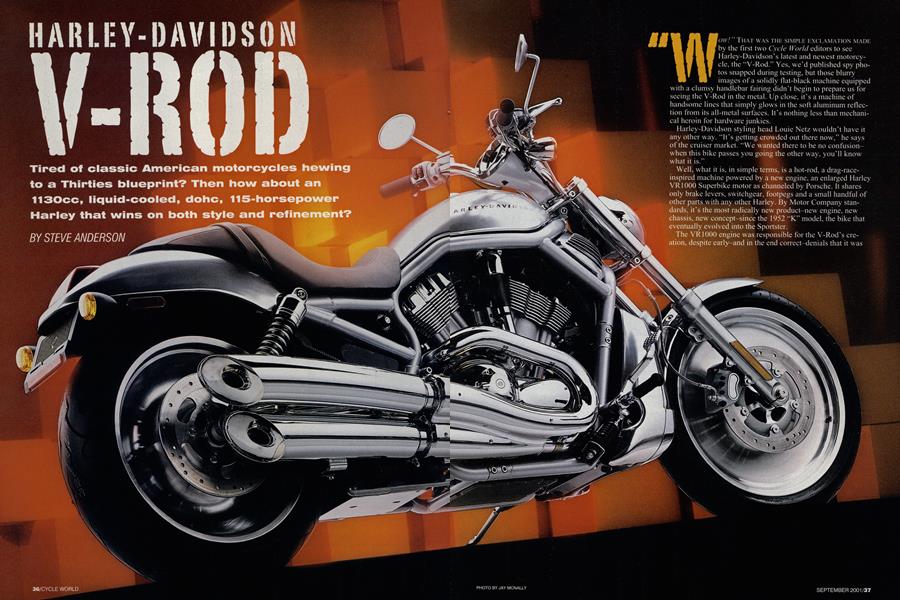

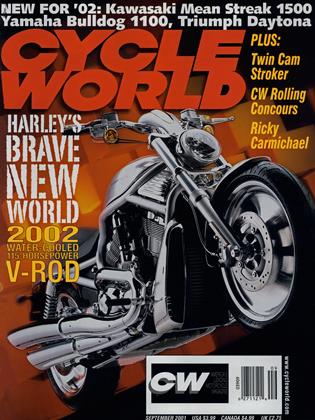

HARLEY-DAVIDSON V-ROD

Tired of classic American motorcycles hewing to a Thirties blueprint? Then how about an 1130cc, liquid-cooled, dohc, 115-horsepower Harley that wins on both style and refinement?

STEVE ANDERSON

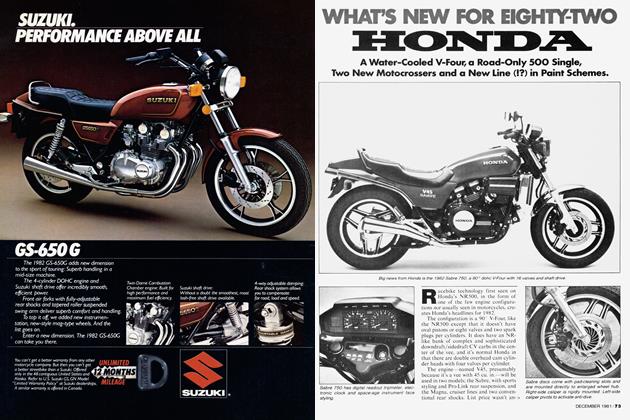

"WOW!" THAT WAS THE SIMPLE EXCLAMATION MADE by the first two Cycle World editors to see Harlev-Davidson's latest and newest motorcyclc, the "V-Rod." Yes, we'd published spy pho-tos snapped during testing, but those blurry images of a solidly flat-black machine equipped with a clumsy handlebar fairing didn’t begin to prepare us for seeing the V-Rod in the metal. Up close, it’s a machine of handsome lines that simply glows in the soft aluminum reflection from its all-metal surfaces. It’s nothing less than mechanical heroin for hardware junkies.

Harley-Davidson styling head Louie Netz wouldn’t have it any other way. “It’s getting crowded out there now,” he says of the cruiser market. “We wanted there to be no confusionwhen this bike passes you going the other way, you'll know it is.”

Well, what it is, in simple tenus, is a hot-rod, a drag-race-

machine powered by a new engine, an enlarged Harley VR1000 Superbike motor as channeled by Porsche. It shares only brake levers, switchgear, footpegs and a small handful of her parts with any other Harley. By Motor Company standards, it's the most radically new product-new engine, new chassis, new concept-since the 1952 “K” model, the bike that eventually evolved into the Sportster.

The VR1000 engine was responsible for the V-Rod's creation, despite early-and in the end correct-denials that it was ever intended for street use. “Obviously,” says Willie G. Davidson dismissing those concerns, “we’d use our own engine.” So a few racing-only VR powerplants made their way to the styling department. “We tried putting them in some of our current bikes, built a VR Softail, just as an experiment,” Davidson explains. “They were so awful we didn’t even take pictures, we just took them apart. But it was important, because we learned what not to do.”

The VR engine is short, without the massive primary drive of other Harley engines. Any bike built around it would require a long swingarm, and would have to make do without all that traditional visual transmission mass. It demanded a new approach. Drag bikes have always had long swingarms and stretched-out front ends, and the racing powerplant found a natural home in those proportions. If Harley were to build a power cruiser, it would be long on performance and style, short on conventional cruiser looks.

Meanwhile, the program began to develop a mass-producible, street-legal powerplant. While the engine would keep the VR architecture, every component would need to change-the VR is simply a racing motor, not designed to balance the competing needs of production, durability and emissions. Unfortunately, Harley’s engineering department was up to its eyeballs at the time finishing the development of the Twin Cam 88 Alpha and Beta engines. So how would the work get done? Enter Porsche.

As well as building its successful sports cars, Porsche runs a large contract engineering business, designing and developing anything from engines to transmissions to full car chassis for automotive manufacturers around the world. In the late Seventies and early Eighties, it developed the never-produced Nova V-Four for Harley. For this new VRbased “Revolution” engine, Harley would once again contract out the design work, with a small team of H-D engineers working directly with Porsche, and testing taking place in both Germany and the U.S.

Jeff Coughlin, Harley Engineering powertrain manager for the V-Rod, notes that the resulting engine still has a lot of VR in it. “We kept the layout the same,” he notes. “It still has an intermediate shaft in the vee, driving the four cams and the water pump. The single balance shaft stayed, in about the same position behind the crank and under the transmission. The clutch is in the same position.” More obviously, it remained a 60-degree V-Twin with four-valve downdraft heads.

But what changed was also extensive. The VR was drysump; the Revolution has a wet sump, “to get rid of the oil tank and plumbing,” says Coughlin. The VR was limited to lOOOcc by racing rules; the Revolution was sized, says Coughlin, “to get the 115 crankshaft horsepower we wanted, in a lower rev range with a nice flat torque curve; that’s how we got to 1130cc.” The boost came from increasing the bore size to 100mm from 98mm, and from lengthening the stroke from 66mm to 72mm. The transmission on the VR had noisy racing-spec gears; the Revolution would get automotive-style helical gears on its second, third and fourth gearsets, the ratios used during tough European noise tests. The VR had screw-type camchain adjusters; the Revolution would get no-maintenance hydraulic adjusters and Porsche 911-type camchain slippers. A team of Porsche and Harley purchasing engineers scoured the world for the best components for the new engine. Some, like the forged Mahle pistons and powder-metal connecting rods, came from Porsche’s favorite supplier list; others, such as IN A bearings and the Delphi fuel-injection ECU, came from Harley’s.

As the engine project proceeded, the V-Rod’s styling defi nition and chassis were also in process. Says Netz, “The exposed frame and the dramatic front end were there from the beginning.” But even that was debatable. Willie G. wanted the fork raked out at 38 degrees, just like a real drag racer, but the engineers were telling him it wouldn’t work. “I told them,

‘You can’t say that until you’ve tried it.’” So engineering built a Sportster with a 34-degree head angle and, using a trick employed on all Harley FL touring models, angled the fork tubes out farther yet through offset triple-clamps to 38 degrees. This also had the added benefit of reducing trail to just 4 inches, and the one-off Sportster handled surprisingly well.

Willie G.’s raked-out look was in.

In other areas, styling gave ground to the engineers. “They told us,” says Netz, “if the bike were to make its performance numbers, it had to have a 12-liter exhaust system. We made that work. They told us it had to have a 10-liter airbox. Well, we knew we weren’t going to hang the airbox on the side, which led to the fuel tank under the seat and the twin shocks.

The frame itself was developed via a long iterative process between engineering and styling.

The stylists wanted a simple tubular frame with clean,

seted joints; the engineers wanted it stiff for good handling. For both reasons, big was good, so 1.5-inch-diameter tubing was used. While the engineers optimized the frame with extensive finite-element analysis, the stylists studied it down to modeling different welds in clay models to achieve the best-looking joint. New manufacturing technology came into play as hydroforming allowed the tubes to be bent into complex three-dimensional curves that even the best CNC bender couldn’t duplicate. The tubes terminate in light-looking investment castings at the steering head and other joints.

The cooling system, in particular the radiator, was another matter. Coughlin reports that Willie G. was emphatic about one thing: “We’re not going to hang a goddamn black box on it.” In talking to us about Japanese cruisers, Davidson was a little milder. “Black paint doesn’t make the radiator go away; it’s not invisibility paint,” he said. So, the radiator had to be an integrated part of the machine. For the V-Rod, that finally came in the wind tunnel, as engineers and stylists working together came up with a design that packaged the radiator above the oil-cooler, both fed by scoops projecting out beyond the sides of the front tire. The area in the turbulent air behind the tire would be blocked off. The scoops would be in the signature aluminum finish of the bike and would advertise their function, not hide it.

The aluminum finish itself isn’t bare metal. Instead, the smooth aluminum airbox cover-where the fuel tank would

normally go-front and rear fenders and radiator scoops are anodized and then given a shot of clearcoat. The parts themselves are amazingly light, most notably the airbox cover. It lifts off readily when the seat is raised, and is made from two .040-inch aluminum sheets bonded together.

When it’s removed, you can reach the V-Rod’s fusebox, radiator catch tank and filler, and the battery-the last tucked right behind the steering head.

And if you want any indication of the power of Harley’s styling department, you only have to look at the front headlight. The beautifully leaned-back piece (an ellipse that’s circular when seen from a straight-on front view) was specially tooled for this bike, at a cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $500,000, or about $45 a bike if you spread it over just the first year’s V-Rod production. It’s glass instead of plastic because Willie G. wanted it so, and it looks fast when sitting still because he designed it that way. It’s pulled up tight against the fork tubes just as on all those drag-racing specials over the years, and it’s a big part of the bike’s signature.

All of this adds up to a visual feast when you see Harley’s new hot-rod. But riding it is even better. Centrifugal compression releases on the exhaust cams allow the engine to spin up quickly with a touch of the starter, and the fuelinjection settles immediately into a stable idle. There’s a very distinct lack of mechanical noise and a nice bass beat from the exhaust. The riding position is the latest “Cclamp” cruiser, with a very low seat height, far-forward pegs, and relatively low and forward bars. The machine feels much lighter than its roughly 600 pounds as you paddle it around, and when you click into first and motor away, your legs stretch comfortably to the pegs.

The V-Rod pulls smoothly from 2000 rpm, then gets eager as the tach needle swings past 3000. At 5000 rpm, the engine has reached into its meaty midrange, and the world is starting to blur more and more as the needle approaches its 9000rpm redline (at which point the tach lighting changes to red, a cute effect, but not very noticeable during the day). Based on power claims and some 1/8-mile runs made at the press launch, we expect this new Harley to run quarter-miles in the low to mid-11 s, pushing toward 120-mph terminal speed.

But more significant than the actual numbers are its effortless, torquey feel, and the overall smoothness with which it delivers that power. That smoothness manifests itself in minimal vibration.

Between the short stroke, light pistons, 60degree vee-angle, counterbalancer and rubber engine mounts, this is one of the least buzzy V-Twins ever made, even including 90degree sportbikes from both Japan and Italy.

In addition, there’s smoothness in the driveline.

With more flywheel than most « eight-valve sportbikes, and with close attention paid to minimizing drive lash, the V-Rod puts its power to the ground without fuss. Even abrupt throttle movements fail to upset it.

At low speeds, the V-Rod wants to fall into comers, likely a product of its steering geometry and big 120-19 front/180-18 rear radial tires. In faster comers, steering is more neutral, with the most noticeable sensations first the solid responsiveness of the machine—credit the massive and short 49mm fork and stiff frame-and secondly the bike’s overall stability. But with only 32 degrees of lean angle each side before the footpegs begin to drag (other hard parts soon follow), this Harley can’t use its tires to their edges or fully make use of its cornering capabilities.

Suspension is a cut above usual Harley fare. Over bumps, the rear suspension is stiff, but the supple fork is constantly at work smoothing even slightly rippled pavement.

The overall impression you get on the V-Rod is of slickness. The new hydraulically actuated clutch requires a little more effort than that of a Big Twin’s, but is marvelously linear and friction-free in its operation. The brakes (four-piston calipers are shared with other Harley models) shed speed smoothly, easily and predictably. The mixture control provided by the fuel-injection is so good that you simply don’t notice driveablity on this bike-it simply does what your throttle hand tells it so effortlessly that you just take it for granted.

So what’s the catch, you might ask? Isn’t there anything wrong with this newest Harley? Well, it might be the $16,500 price tag (and good luck getting one for that) or, if you’re really fussy, the slightly notchy shifting (we were told effort would be reduced by roughly half in production). But we suspect the bike’s worst fault is this: Harley only plans to build 11,000 V-Rods for all markets in 2002. We’re pretty sure that’s nowhere near enough to go around.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSpanish Flyers

September 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsAncient Beemer Update

September 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTurning

September 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Unleashes Bulldog V-Twin!

September 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupNew Life For A Legend

September 2001 By Matthew Miles