BOLT FROM THE BLUE

CYCLE WORLD EXCLUSIVE

SURPRISE! HARLEY-DAVIDSON GETS INTO THE SPORTBIKE BUSINESS

STEVE ANDERSON

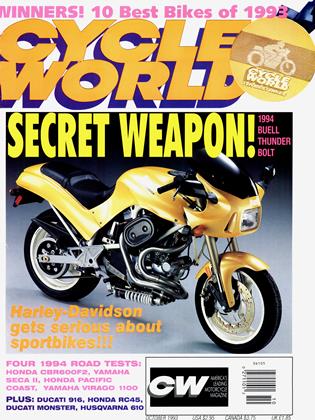

THE NEW, 1994 BUELL Thunderbolt promises to be the best handling, most exciting, most livable sportbike ever built by an American company. When it goes into production early this winter, it’ll be priced to offer more value than any previous Buell motorcycle. And yet that isn’t the key to this story.

The real story is what’s behind the Thunderbolt: The new Buell Motorcycle Company, formed over the ashes of the Buell Motor Corporation in late January.

The new company is 51 percent owned by Erik Buell, 49 percent owned by-pause for a drum roll-the HarleyDavidson Motor Company.

What’s going on here? Why would Harley-the company that owns the bigbike custom market, the company that dominates the overall U.S. motorcycle market in total revenues-why would Harley buy a minority interest in a tiny concern that’s never produced more than 120 expensive and somewhat eccentric sportbikes in its best year?

According to Harley-Davidson President Jeff Bleustein, “We’re not interested in selling a few hundred Buells a year; we want to sell thousands.”

Bleustein sees Buell as Harley’s entry into the “sport-custom” market, or what the rest of us might simply call the sportbike market. Buell offers Harley a freedom that the company needs, explains Bleustein: “We’ve encountered problems when we’ve tried to do anything different than a classical Harley-Davidson. Starting with the XLCR Cafe Racer in 1977, continuing with the FXRT-probably even with the FLT-every time we’ve made something that looks a little different from what a Harley-Davidson should look like, it gets spit out by the marketplace, it gets rejected. Some of our best-performing bikes were rejected.” Even now, Harley’s least modem designs-the 883 Sportster and the Softail models-are its best-selling.

Buell offers Harley a way to diversify without diluting its image. As Bleustein says, “We didn’t want to be limited to building a new XLCR. We’re going to try to do some things a little differently. It’s probably a lot easier to do them under a different banner. We don’t have the same rewards; we only own 49 percent of Buell Motorcycle Company, and everything we do we divide by two. But half a loaf is better than (not even being) able to play in that marketplace.”

Tf the new company offers H-D a chance to expand its hori zons, for Erik Buell it has more immedi ate advantages. The old Buell Motor Corp. had been struggling to stay afloat ever since its founding in the mid-’80s. It never had more than $200,000 in capital-which only seems like a lot of money until you start thinking about how many people that will hire, how many parts it will buy, or how many months’ rent it will pay. In comparison, the total investment in Britain’s new Triumph motorcycle concern has been reported as $ 110 million, and BMW claims to have spent $100 million on development and tooling for its new R1100 Boxer Twins.

The lack of money shaped Buell Motors, The first bikes were built in Erik’s own garage; later the company moved into more luxurious accommodations: a small and rustic garage/workshop on the edge of downtown Mukwonago, a village about 30 miles out of Milwaukee, in the green Wisconsin countryside. The old Buell building looked as if Model Ts were once repaired there; it might even offer room to park six of them inside.

Buell Motors’ bikes were similarly shaped by economic struggle. Buell, gifted engineer and ex-national-class roadracer, focused on the basics. He designed a short and stiff steel-tube frame that used a rubber-mounting system much like that used on Harley FXR models-a natural, as Buell had designed that chassis when he worked on Harley’s engineering staff. Harley engines were a natural, too. As an exHarley insider, Buell was in the unique position of being able to buy, at first, XR1000 engines and then Sportster 1200 engines, with Harley not even demanding payment up front. The Harley engines made Buells all-American machines, and meant that adventuresome Harley-Davidson dealers could be persuaded to sell them. Almost all parts were jobbed out, with Buell Motors acting only as designer and point of final assembly.

But Buell never had the money to order parts in economic quantities, and while the motorcycles were fundamentally right in design-the frame in particular was a thing of beauty-the first motorcycles didn’t have the detailing and glow of quality that would have helped justify their high price.

Buell Motors fought to change that in the last few years, spending precious funds to bring manufacture of bodywork and painting operations in-house.

Its last RS and RSS 1200 models had as nice a finish as anything this side of a Rolls-Royce, but the price soared to $15,000 and beyond. The company was trapped in a tiny niche, building bikes too expensive to sell in large quantities, and the small quantities it sold kept it from building less expensive bikes.

Only a major investor could spring it from that trap. Enter Harley-Davidson and the Buell Thunderbolt.

As the first product of the new Buell Motorcycle Company, the Thunderbolt sets a direction for its future. The short amount of time to get a 1994 model ready (the new company was only formed in late January) dictated that the Thunderbolt would be derived from previous Buells and still be powered by the big Harley Sportster engine-but with some very significant changes.

According to Buell, the goal for the Thunderbolt was to build a machine “that was both more Harley, and more Buell.” And, he explains, one that was more in the mainstream of the sportbike market than previous Buells. The idea, says Buell, was to make the Thunderbolt “more Harley” by showing more of the engine, “more Buell” by showing more of the frame and mechanicals, and more mainstream by making it fit more people.

Buell and his staff measured more than 40 sportbikes from Japan and Europe, compiling a database on riding positions. They contrasted those numbers with their own subjective judgments of comfort, and with those from magazine reviews. They discovered, according to Buell, that “with those bikes on the edge of the envelope, you get complaints.” Suzuki’s GSX-R was out on the edge, and so were previous Buells. Perhaps that shouldn’t have been a surprise, because all previous Buell models sprang from the first, radically streamlined RR1000 racebike, and its riding position had been copied from a Honda 500cc GP racer.

The Thunderbolt, aimed at street rather than track, would use a shorter fuel tank to position the rider almost 2 inches farther forward than the Buell RS or RSS, with the footpegs 5 inches forward of the RSS position. While an adjustable riding position was considered for the Thunderbolt, it was thrown out because “simplicity dictated otherwise,” and because Buell found it possible to build a bike that would fit a very wide range of rider sizes without it. Unfortunately, the new riding position demanded space for the rider’s knees that had previously been occupied by the wide tubular space-frame. It would have to be redesigned.

he Thunderbolt shares its wheelbase and steering geometry with last year’s Buell motorcycles: 55 inches, 25 degrees and 3.9-inches of trail. But it barely shares a tube in its frame with the old bikes. Once the riding position set change in motion, nothing could stop it. The new bike would have a more visible frame, so that it was made more symmetrical and simplified. Because the bike was being positioned more against BMW’s R1100RS and Ducati’s 900SS than against repli-

racers, Harley’s low-maintenance, belt final drive was deemed appropriate. But making room for that belt and a wide, 170/60 rear tire meant relocating the engine twotenths of an inch to one side. The old passenger pegs were mounted on loops welded to the frame; on the new machine, they would be more neatly carried on aluminum sideplates. The under-engine shock was moved an inch-and-a-half to the right, to make room for one serious muffler.

This last change reflected an important aspect of Buell’s new relationship with Harley-Davidson. Where Harley had once supplied only standard Sportster engines to Buell Motors, now Harley’s engineering department would develop custom-tuned engines for Buell Motorcycles. Everyone agreed that the Thunderbolt needed more power than provided by a stock Sportster; the question was how to get it in the few months available.

The answer was as close as getting rid of the Sportster’s tiny and restrictive mufflers and air filter. Harley engineers knew that these cost power, but also knew that there was no way around that given Sportster styling constraints. For the Thunderbolt, Buell told them, “Build a muffler that works, no matter how big, and I’ll find a way to package it.” What resulted was a huge, free-flowing black can that tucks under the engine, a muffler so effective that it allows the Thunderbolt to comfortably pass noise tests while running what’s basically a low-restriction Screaming Eagle air filter. It also allows the prototype 1203cc Thunderbolt engine to pull 76 horsepower (at the countershaft sprocket) on Harley’s dyno, almost 20 percent more peak power than the engine in a ’94 1200 Sportster, and more power than any standard Sportster ever, XR1000 included.

Styling was the final element to come together. It was done by Buell and industrial designer Mike Samarzja, with help from the rest of the Buell staff. Buell has much to say about it: “The style and look took a great deal of effort. The Thunderbolt was styled as a whole; it’s really the first one we really got right. We had a lot fewer constraints on what we could change and what we couldn’t. We wanted everything to fit in, the fairing to flow into the gas tank. We spent hundreds of hours. We wanted it to be simple, clean and very pretty.”

For the tank and seat, Buell was looking for the kind of sensuous curves that were once found on Italian race cars, “The kind,” he says, “you can’t wait to touch. I don’t see that in motorcycling. People are driven too much by racing, and racing styling. There are classic lines that look right on bikes, but they’re not the only lines.”

When first encountered the Thunderbolt, Buell and his staff were thrashing to finish the yellow prototype you see here; it has a few non-functional parts that restrict it to show use only. Two days after its trip to the photo studio for Cycle World's exclusive story, it was rushed to Harley’s 1994 dealer show. Only days earlier, Buell had put together a slightly rougher Thunderbolt prototype that I could ride, the blue bike pictured on the next page.

While firm conclusions await production machines-which will almost certainly differ in a few details from these early prototypes-the first Thunderbolts still tell a few tales. First, just as on previous Buell models, the rubber-engine-mounting system really works. Buells are perhaps the smoothest big Twins of any brand, BMWs and Ducatis included. Their rubber-mounts simply polish the rough edges from vibrations; gentle pulsing still reaches you occasionally, but it’s far more reassuring than bothersome.

Second, the new riding position is a winner. On an older Buell, you sit back while folding forward to reach the bars; the fuel tank and fairing partially lock you in place. With the Thunderbolt, you sit forward, as you would on a Honda VFR750 or CBR600F2.

The position encourages you to move around, and I found myself riding the bike more aggressively because of that.

Third, the new exhaust system may indeed meet noise laws, but that doesn’t stop the Thunderbolt from sounding like a proper rumpity-rump motorcycle. There’s some engineering trickery there, with the muffler optimized to the details of the mandatory noise test rather than simply squelching all sound, and some just plain common sense. The mechanical noise on a Sportster engine is all on the right side with the cams, pushrods and final drive, so the Thunderbolt’s exhaust is directed out the left, balancing the noise levels on the two sides.

And last, after years of refinement and experiments with tires, steering geometry, springs, dampers and weight distribution, this blue Thunderbolt handled very well indeed. It would flick into corners as quickly as any 600, and the heavy-flywheeled Harley engine felt as if it consciously sought out every bit of available traction on the way out. The huge, 13.4-inch front disc and six-piston caliper were powerful enough to stand the short bike on its nose. In total, the Thunderbolt was a very easy bike to ride quickly.

In fact, the entire Buell operation is streaking along at a feverish pace. In early August, Buell Motorcycles moved into a modern, 10,000-square-foot facility in East Troy-even farther into the Wisconsin countryside than Mukwonago. A 20,000-square-foot building is scheduled to be built next door within the year. For 1994, because of the late start, just 300 Thunderbolts are scheduled for production, and the tentative price is $12,500. Harley is looking for Buell dealers, and while it’s offering existing Harley dealers first shot, there’s nothing automatic about the process; they have to prove their commitment to selling something new and different. The dealers who earn the right to

put up a Buell sign will soon have more to sell than the Thunderbolt. Buell plans to release bikes both more and less expensive in the future, some perhaps much racier, some perhaps much more sport-touring oriented. Everyone knows that Harley has long been working on a liquid-cooled, fourvalve Superbike engine; as to whether that will eventually show up in a Buell, no one is saying.

For me, though, the strongest impression came from seeing the yellow Thunderbolt go together. Its new Buell instruments arrived just a day before our photo session. For cost reasons, previous models have used pods lifted directly from the 1200 Sportster, and Buell admitted that after years of financially squeaking by, it was hard for him to sign a purchase order that authorized $7000 to tool a custom instrument face. But the white-faced instruments, clean and contemporary, and emblazoned with the Buell Pegasus logo, sit on a redesigned and classy looking dash telling a story: This is a new and serious motorcycle company, and you’ll be hearing a lot more from it in the future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1993 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1993 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

October 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1993 -

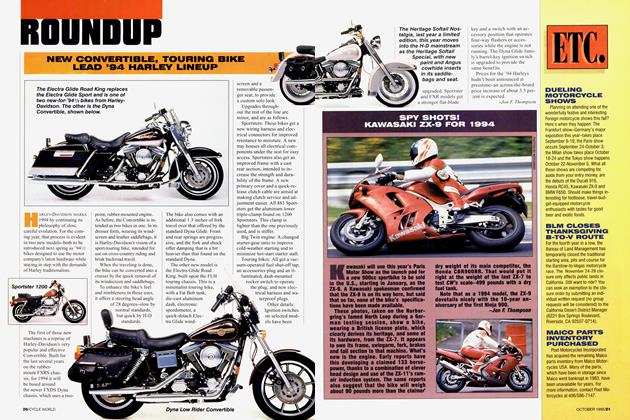

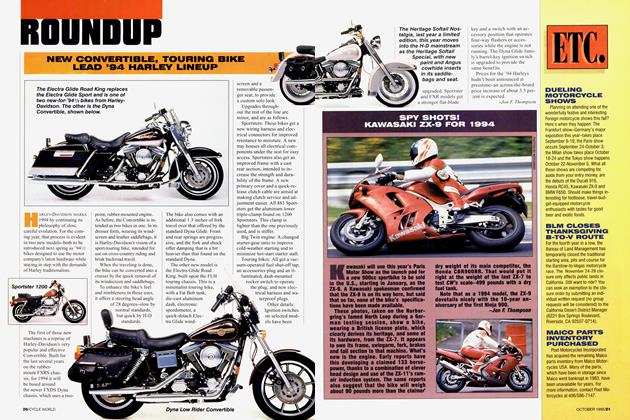

Roundup

RoundupNew Convertible, Touring Bike Lead '94 Harley Lineup

October 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Spy Shots! Kawasaki Zx-9 For 1994

October 1993 By Jon F. Thompson