CYCLE WORLD EXCLUSIVE

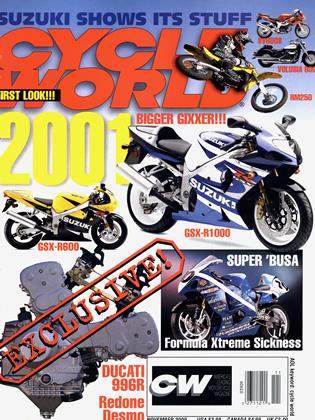

996R

SPECIAL SECTION

A new Ducati V-Twin for 2001-and beyond

BRIAN CATTERSON

DUCATI IS A COMPANY IN NEED OF A NEW engine. It might not be readily apparent watching Ben Bostrom and Troy Bayliss run at the front of World Superbike races, but it's true. And why wouldn't it be? The current 996cc V-Twin grew out of the 851 of 1988, so it's been winning for more than 12 years. Aprilia's and Honda's race Twins, on the other hand, are in their infancies, and as such pose a serious threat to Ducati's future. Time for a change.

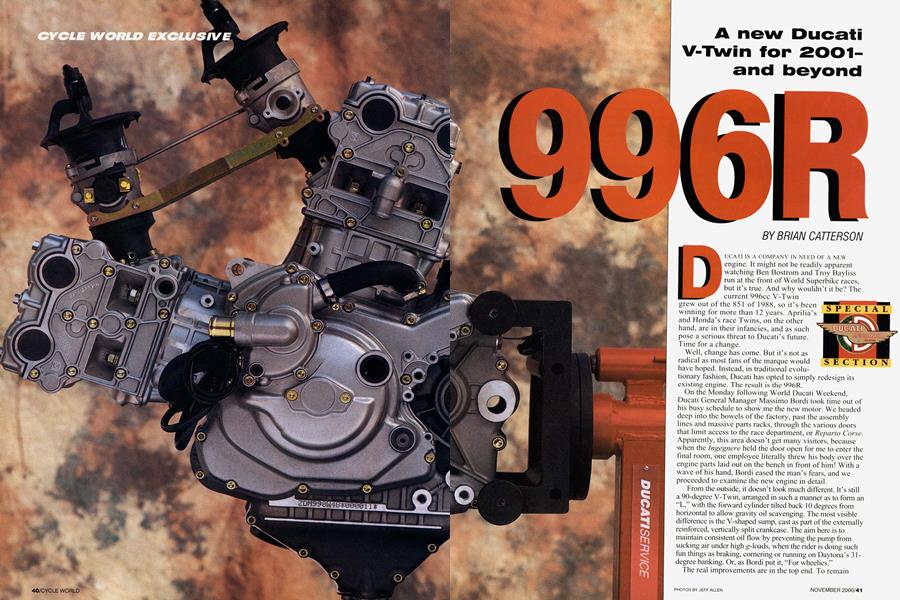

Well, change has come. But it’s not as radical as most fans of the marque would have hoped. Instead, in traditional evolutionary fashion, Ducati has opted to simply redesign its existing engine. The result is the 996R.

On the Monday following World Ducati Weekend, Ducati General Manager Massimo Bordi took time out of his busy schedule to show me the new motor. We headed deep into the bowels of the factory, past the assembly lines and massive parts racks, through the various doors that limit access to the race department, or Reparto Corse. Apparently, this area doesn’t get many visitors, because when the Ingegnere held the door open for me to enter the final room, one employee literally threw his body over the engine parts laid out on the bench in front of him! With a wave of his hand, Bordi eased the man’s fears, and we proceeded to examine the new engine in detail.

From the outside, it doesn’t look much different. It's still a 90-degree V-Twin, arranged in such a manner as to form an “L, with the forward cylinder tilted back 10 degrees from horizontal to allow gravity oil scavenging. The most visible difference is the V-shaped sump, cast as part of the externally reinforced, vertically split crankcase. The aim here is to maintain consistent oil flow by preventing the pump from sucking air under high ^-loads, when the rider is doing such fun things as braking, cornering or running on Daytona’s 31degree banking. Or, as Bordi put it, “For wheelies.”

The real improvements are in the top end. To remain competitive, Ducati needs more power, which means higher revs. But the 996 had reached its limit, as ascertained by the banks of test benches within the race department. While we were there, technicians were conducting a “cold test,” wherein an engine is spun to stratospheric revs via an electric motor to find its mechanical limit. There’s also a “hot test,” in which an engine is started up and run, with all functions controlled by a computer. This occasionally entails downloading the data from a previous race and re-running the entire event-every nuance of throttle action, each gearchange, etc.-in an attempt to recreate a problem, or determine if a remedy has worked. And we wonder why race teams need sponsors?

romic engine. In penning lí

Bordi landed his job at Ducati on the strengths of his 1973 engineering thesis on a four-valve-per-cylinder desmodromic engine. In penning his work, Bordi borrowed from state-of-the-art Formula One technology, which at the time meant the Ford Cosworth DFV V-Eight, pinnacle of normally aspirated engineering prior to FI’s “Turbo Age.”

He apparently wasn’t the only one who had this notion. While reading about the Cosworth in The Anatomy & Development of the Formula One Racing Car by Sal Incandela, I came upon this intriguing snippet: “There is little that can be done to improve the power output of a 3000cc Cosworth normally aspirated racing engine... except (to adapt) a desmodromic valvegear system.” Great minds think alike!

When it came time for him to make his idea into metal, however, Bordi had second thoughts.

“Try to imagine in 1986, when I tried to improve the Pantah,” he recalled. “At that time, it was a two-valve, aircooled, 860cc engine that made 88 horsepower. I remember at the Bol d’Or, we were 11 seconds per lap slower than the Japanese Fours. At the time, I thought, should we make a Four or improve the Twin? I decided to improve the Twin, to maintain our identity.

“It’s important to maintain an identity,” Bordi continued. “Every time Porsche tries to change its engine design, no one buys it.”

That identity also apparently extends to an engine’s sound, because like Harley-Davidson, Ducati has attempted to trademark its distinctive exhaust note, so far unsuccessfully.

Determined to stick with a V-Twin, Bordi set about creating the first production desmoquattro, the 851. In doing so, he specified a 92mm bore and 64mm stroke-equating to a bore/stroke ratio of 1.44:1-and paired valves angled at 40 degrees. Cylinder dimensions were gradually increased over the following decade, yielding displacements of 888, 916, 926, 955 and, finally, 996cc, at which point the cylinders measured 98 x 66mm, for a bore/stroke ratio of 1.48:1.

But technology marches on, and today’s V-10 FI engines have bore/stroke ratios approaching 3:1, with nearly flat combustion chambers. The 998cc 996R takes another step in that direction with a 100mm bore and 63.5mm stroke, equating to a bore/stroke ratio of 1.57:1, and valves angled at a shallow 25 degrees. Figures that, not coincidentally, are nearly identical to those of Honda’s RC51.

Adapting the existing 996 engine to this new specification wasn’t easy, because as included valve angle decreases, the valves become more vertical, and thus closer together. This proved problematic on the Ducati because the desmo valvegear resided right where the valve stems needed to go.

The obvious solution would have been to abandon mechanical valve actuation and adapt conventional valve springs like everyone else. But desmodromics are a Ducati signature, as important to the marque’s identity as pushrods are to Harley-Davidson. They would have to stay.

To find an answer to this dilemma, Ducati in 1998 turned to Ingegnere Marchetti, a retired Ferrari designer who sadly died shortly after completing this project. His solution was to redesign the valve-actuation system. Where Bordi’s design had positioned the opening, finger-type cam followers and the closing, forked-end rocker arms one above the other between the camshafts, Marchetti’s design relocated the opening cam followers outward, to the front and rear edges of the cambox. In the process, the followers and rockers were made smaller, perhaps 60 percent the size of their predecessors. Also helping to save space are investment-cast steel sparkplug tubes, whose lmm-thick walls are 75 percent thinner than their aluminum counterparts.

But while much of the top end shrank, the valves grew. The 2mm-larger bore allowed the valves to increase in diameter from 36 to 40mm on the intake side and from 30 to 33mm on the exhaust side. Compression ratio is unchanged at 11.5:1, but the flat-topped pistons now have one long relief for each pair of valves instead of four individual pockets as before.

Marchetti’s automotive influence is apparent in the removable valve covers, which conceal cams that spin directly in the aluminum heads, without bearings, and are held in place by bolted-down caps. The entire cambox is lower in profile, which in theory should allow the engine to be positioned closer to the front wheel for a greater frontend weight bias.

Other refugees from the FI world include the now-common “stick-type” coils, which snap directly onto the sparkplugs, and the fuel-injection system. World Superbikes have utilized as many as three injectors per cylinder, but the FI standard is now one per. As such, the 996R’s Marelli system positions a single “shower-type” injector well upstream from the intake ports for optimal fuel atomization, a setup Ducati developed on its works Superbikes and subsequently debuted on this year’s 748R. The intake tracts themselves are noticeably shorter than on the old 996, in the interest of highrpm power.

What kind of bike will this new engine propel? For the moment, it will be the same old trellis-framed 996, albeit with its red-painted monoposte> bodywork made from carbon-fiber instead of plastic, and with upscale Öhlins suspension front and rear. For 2001, just one version of the 996R will be offered, in numbers sufficient to ensure its homologation for World Superbike competition. Beyond that, though, three models are envisioned: the basic street model, a hotted-up SPS version and a racespec Corse. Prices and availability were scheduled to be announced at the Munich Show.

According to Bordi, the twin

goals of this project were a 10 percent power increase in street and race trim, and a rev ceiling in excess of 13,000 rpm. Sure enough, claimed output has risen from the 996 SPS’s 123 horsepower at 9500 rpm and 73 foot-pounds of torque at 7000 rpm to the 996R’s 135 bhp at 10,200 rpm and 74.5 ft.-lbs at 8000 rpm. In World Superbike trim, the new engine should produce in excess of 180 bhp. That ought to keep Ducati competitive for a few more years.

In fact, Bordi doesn’t buy into the scuttlebutt surrounding his team’s lukewarm performance in this year’s World Superbike Championship.

“Honda is there (in the points lead) only because Fogarty isn’t,” he proclaimed. “Bayliss won, and he’s a new rider!”

When King Carl gets his hands on a 996R, we’ll know what’s what.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontShameless Plugs

November 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Convertible

November 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGp Four-Strokes

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupDan Gurney's Alligator: Alternative Corner Carver

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHart Attack

November 2000 By Eric Johnson