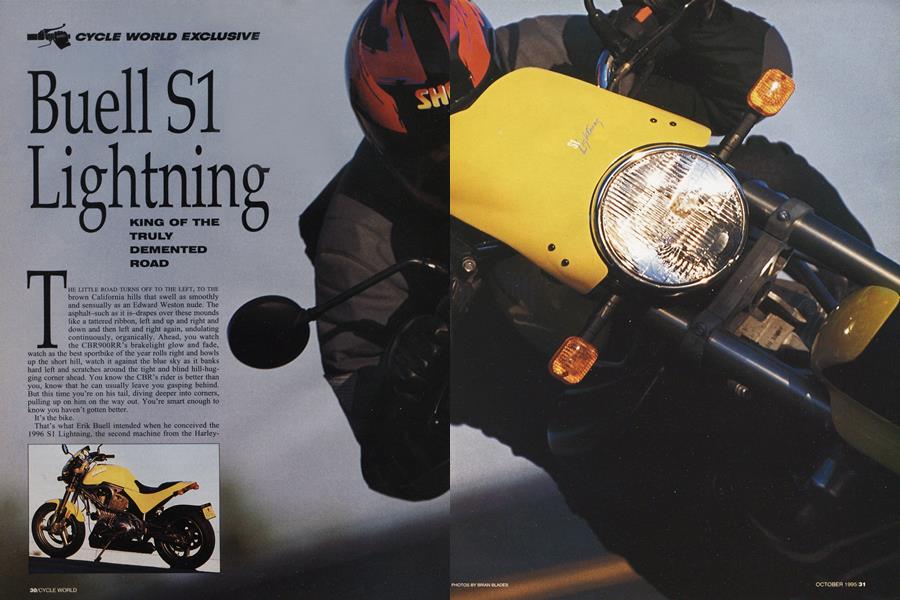

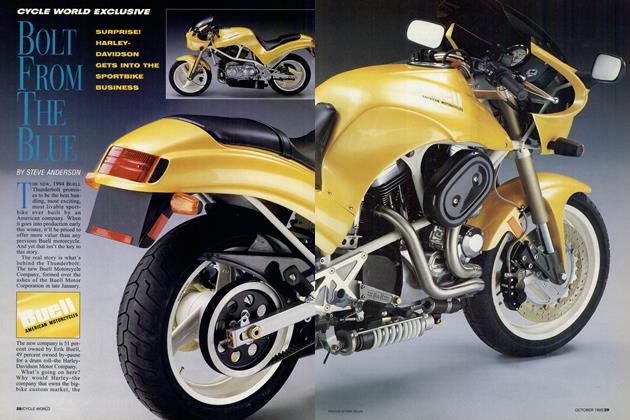

Buell S1 Lightning

CYCLE WORLD EXCLUSIVE

KING OF THE TRULY DEMENTED ROAD

THE LITTLE ROAD TURNS OFF TO THE LEFT, TO THE brown California hills that swell as smoothly and sensually as an Edward Weston nude. The asphalt—such as it is—drapes over these mounds like a tattered ribbon, left and up and right and down and then left and right again, undulating continuously, organically. Ahead, you watch the CBR900RR’s brakelight glow and fade, watch as the best sportbike of the year rolls right and howls

up the short hill, watch it against the blue sky as it banks hard left and scratches around the tight and blind hill-hugging corner ahead. You know the CBR’s rider is better than you, know that he can usually leave you gasping behind. But this time you’re on his tail, diving deeper into comers, pulling up on him on the way out. You’re smart enough to know you haven’t gotten better.

It’s the bike.

That’s what Erik Buell intended when he conceived the 1996 SI Lightning, the second machine from the HarleyDavidson-affiliated Buell Motorcycle Company. The SI Lightning, says Buell, isn’t some standard, isn’t a “dumbeddown” and compromised machine designed to appeal to the broadest audience at the lowest price. Instead, it’s a pure sportbike-it just doesn't happen to have bodywork.

While the SI bears a resemblance to Ducati’s M900 Monster, its roots reach farther back, to 1989. The then Buell Motor Corp. was looking at doing a naked bike, a machine that would show off its frame and engine, a machine requested by Buell dealers and motorcycle magazines alike. The idea advanced as far as a prototype, a “fun little bike,” reminisces Erik Buell. “It was like riding a 250 roadracer without a fairing.” But there was a problem. It simply couldn't be built given the precarious finances of the pre-Harley Buell Motor Corp.

But after last year’s successful introduction of the S2 Thunderbolt, Buell returned to the idea of a naked sportbike. “The original concept was to just change the styling of the Thunderbolt,” says Buell. “But it ended up being a lot different.” As the idea evolved, Buell and his crew became fixated on “stretching the envelope,” on producing a high-performance motorcycle that could go fast on any type of road-even dirt or gravel. While there would be influence from roadracing, other competition machines-dirt-trackers, motocrossers and European Supermotard racers—would also serve as role models. The key, says Buell, was “a very active riding position-up front and over the handlebars.”

So the changes began. The Thunderbolt would contribute chassis dimensions, and an H-D Sportster-based V-Twin would still power the Lightning, but almost everything else would be different. The bodywork of the Thunderbolt was the first to go; in its place are just three pieces: a tiny flyscreen fairing, a rotomolded plastic fuel tank and a compact tailsection. Shorter by 3 inches, the new tank places the rider well forward; the back of the tank is only about 5 inches across, and the front of the seat and tailsection are equally narrow. Footpegs have moved back about 2 inches from the Thunderbolt and, by attaching directly to the frame, have been narrowed almost 2 inches. Says Buell, “The styling is intended to capture the essence of a tool for sport riding; the best tools fit a human being.”

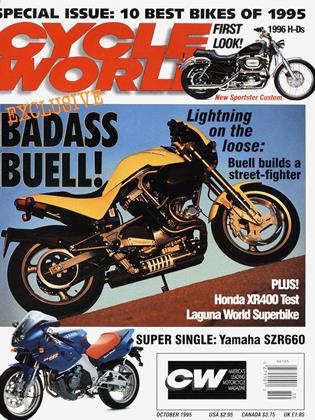

When you first see the Lightning, the styling shocks. The fluorescent yellow paint glows so brightly that there’s almost a halo around it. A 600cc four-cylinder sportbike parked alongside fairly dwarfs the short (54.5-inch wheelbase), stubby and low SI. The truncated tailsection definitely has been influenced by dirt-trackers, and you’ve never seen a license plate mount to an inner fender before. The airbox, vaguely scooplike, is a big flat-black breadbox stuck just under the right front of the tank.

When you swing a leg over, you’re struck immediately by the Si’s narrowness, how naturally your legs wrap around the gas tank, the lowness of the 30.9-inch-high seat. The narrow seat feels better than its minimal dimensions predict, though you wonder how it will be on a long ride. The pegs are beneath you, right where they belong, and the 32-inchwide, 7/s-inch-diameter handlebar places your hands far apart, elbows bent, your torso in a slight forward lean. Normal sportbike hand controls-Nissin master cylinder and levers, and CEV switchcs-fit your hands, unlike the bulky Flarley items used on previous Buells. The big airbox is completely forward and clear of your right knee, a first-ever for a machine carrying a Milwaukee V-Twin. The only bit of hardware that seems out of place is the heat shield on the rear exhaust pipe, which pushes lightly against the inside of your right leg. All-in-all, though, the Lightning sits like a big dirtbike. This could be fun, you think.

From the beginning, Buell saw the Lightning as an uncompromised design, a performance machine with the best suspension, wheels and tires that could be fitted. But it also needed a high-performance engine. The Thunderbolt powerplant made outstanding bottom-end and midrange power, but ran out of steam too early. To be credible, the Lightning needed to be stronger-a lot stronger.

Gary Stippich was the man sent to find the additional oomph. The soft-spoken Harley-Davidson engineer was the perfect J candidate for the job. He’d once been in charge of Sportster engine design, and in the early Eighties helped Harley Racing’s legendary Dick O’Brien develop the XR1000. In the few years before being named Manager of Buell Powertrains, he had been the engineering liaison to manufacturing operations at Harley’s Capital Drive engine plant. Stippich knew not only the design of the Sportster engine inside and out, he also knew every aspect of its manufacture, down to the names of the machine operators who turned its flywheels and cut its gears.

According to Stippich, finding the power while maintaining reliability was the easy part; there’s a lot of margin built into the stock Sportster engine. Doing it while meeting sound and emission laws, and while fitting into Harley’s manufacturing process, those were the hard items. The power increases come from the obvious: longer duration camshafts (the “Screamin’ Eagle” cams from Harley’s accessory catalog), a higher compression ratio, less flow restriction in the intake ports with the use of shorter valve guides. The compression ratio comes from a new head casting, unique to this Buell engine, that unites the tight hemispheric combustion chamber of the 883 Sportster engine with the big valves of the 1200. That chamber and a new ignition curve allow the higher compression while stopping most of the detonation that occasionally rattles earlier Thunderbolts and 1200 Sportsters.

Keeping it sound-legal, though, fell to Harley-Davidson’s “Triad Group,” a triumvirate of Harley engineers, the company that manufactures Harley’s mufflers and an independent acoustics consultant. For the first time ever, they were given almost complete design freedom, rather than the narrow confines of a pair of shortie duals. “Design a free-flowing airbox and muffler that lets us peak this engine at 6000 rpm or greater and still meet an 80-dB sound limit, and we’ll find some way to package these on the motorcycle,” they were told. So the Lightning wears an even bigger automotive-looking muffler than the Thunderbolt, and a bulky airbox so full of ram tubes and Helmoltz resonators it couldn’t have been designed without the use of sophisticated computer modeling. Put it all together, and the Lightning makes 75.5 horsepower at the rear wheel-almost 14 horses more than the Thunderbolt, roughly 50 percent more than a 1200 Sportster-accompanied by a staggering 60 footpounds of torque or more from 2500 to 6200 rpm.

Push the starter button, and you know instantly that this isn’t your standard Harley powerplant. The tach needle dances up too quickly-the result of lightened flywheels with almost 25 percent less inertia-and the sound texture is different. Quieter, deeper, more sophisticated. The Lightning pulls hard from 2000 rpm; down low, rubber mounts take any harsh edge from vibration but still allow a rumble through the handlebars. As you reach 4000, though, even that muted vibration fades away, and the bike leaps ahead into the meat of its band, pulling hard to the 6800-rpm rev-limiter. A quick shift to second snaps the front wheel off the ground. The Lightning feels fast, just as its quarter-mile time indicates (11.77 seconds at 113 mph on a hot day, slowed slightly by a secondthird shift that required extra care). Run it all the way out in fifth, and you’re hauling along right around 130 mph. This is one fast Twin.

Performance increases demanded upgrades in running gear, as well. The Lightning gets the latest WP suspension components, optimized for one-up riding. The front brake is a new design using a single, mammoth 13.4-inch floating disc on a lightweight carrier, stopped by a cast, six-piston Performance Machine caliper. Marchesini aluminum wheels carry the newest Dunlop SportMax II radiais. The Lightning’s frame shares geometry and wheel placement with the Thunderbolt, and is equally stiff, but shares few tubes with it. It also provides a normal amount of steering lock, making U-turns easier than on previous Buells.

You discover that how well the Lightning works depends on where you’re riding it. On the freeway, it’s okay, better than most racer-replicas. Though the prototype seat is narrow, hard and poorly shaped-easily one of the least comfortable around-the overall riding position is excellent. The high-mounted instruments and little flyscreen fairing break the wind on your chest; not until you’re ripping along at 90 do you start to turn into a sail. Tuck low behind the little fairing, and you can run out to top speed with decent protection. The Lightning handles roads with fast (over 100-mph) sweeping comers with aplomb, but it’s no match there for a higher-powered, more aerodynamically faired sportbike. Sweepers also point out a problem shared with most unfaired bikes with high handlebars: it’s easy to feed body movements back into the bars, starting what feels like an incipient wiggle. The secret is to plant yourself solidly on the bike, so as not to let the wind buffet you around.

On roads with tighter corners, the Lightning starts to come into its own. There, the riding position simply pumps you up with confidence, and the engine-antique heritage and all-might just be one of the great sportbike powerplants for these conditions. From 4000 to rev-limit, it pulls so hard, so smoothly, so crisply, and with so little driveline snatch, that you find yourself opening the throttle far earlier than you would on a Four. Head toward a hairpin comer, one marked with a 10or 20-mph caution sign and scattered with patches of sand or gravel atop rough asphalt, and the wide handlebar encourages you to pitch the SI in hard anyway, while the infinite ground clearance asks you to ride as if you were on a dirtbike, pushing the SI down while your body remains upright. Get hard on the throttle as you reach the apex, and smooth power rockets you out. Compared to a four-cylinder sportbike with clip-ons, on a road stitched together with corners like that, the Lightning feels like cheating.

It’s also something of a bargain-at least by HarleyDavidson standards-with a price tag of $9950, almost $2000 less than that of the Thunderbolt. Where’s the cost savings come from? From simplification and the fact that Buell, the company, is getting better at building motorcycles. All-inall, a Lightning has approximately 100 fewer parts than a Thunderbolt. Investment-cast brackets (made by a company that manufactures frame lugs for high-end bicycles) carry rubber engine mounts and footpeg mounts, eliminating the weight and expense of bolt-on aluminum peg carriers while looking better to boot. Also saving weight and money are a rotomolded plastic oil tank (developed and tested by Harley engineering, but rejected by Willie G. for styling reasons) and a compact, sealed lead/acid gel-cell battery that can mount on end. The reduced parts count helps keep the Lightning’s dry weight down to a reasonably svelte 446 pounds, a near record for something displacing 1200cc.

Long after the ride, you’re still thinking about the Lightning. It’s by no means a perfect motorcycle. Oil blowby dripped from the airbox; the seat was a board; the suspension-while well controlled-transmitted some harshness over square-edged bumps; the rear exhaust cooked your right thigh in stop-and-go traffic; the clutch pull took more than average effort; and the brake lever was a long reach from the handgrip. You think about those annoyances, and then you think about what the Lightning was like on tight and twisty Tepusquet Road. On that narrow and bumpy old asphalt, the Lightning could run away and hide from a machine as fast and sophisticated as a CBR900RR. You think about that, and the grin you wore under your helmet that day comes back. Maybe, just maybe, Erik Buell has expanded the envelope in a way that you have to have. £3

BUELL S1 LIGHTNING

SPECIFICATIONS

$9995

EDITORS' NOTES

I’VE ALWAYS SAID I’D OWN AMERICAN iron only when there was an offering that matched the price and performance of foreign sportbikes. Until now, Buells have been interesting, but not something I’d even remotely consider buying. Personally, I see little honor in paying more for less, not where backroad performance is concerned, not when you plan on using every ounce of acceleration, braking and lean angle a bike has to offer.

That’s where the SI Lightning hits home. Sure, lots of bikes will outgun the Buell in a straight line, but the SI counters with a well-rounded performance package. Here’s a bike that truly satisfies my sport-riding needs.

Even so, $ 10,000 is a lot of money to spend on a naked sportbike, especially when there’s serious corner-carving hardware available for thousands less. For me, then, Buell’s latest offering remains a tough sell-but it’s getting close.

-Don Canet, Road Test Editor

LORD HAVE MERCY, THIS THING SERVES up more thrills than a Tom Hanks moonshol! With 75 horsepower and tons o’torque on tap, the Lightning’s quick-revving, son-of-Sportster Twin is an honest-to-goodness hot-rod. Heck, it may even be a candidate for inclusion in the Motorcycle Hall of Fame.

Then there’s that stubby chassis, which imparts razor-sharp, almost intuitive, reactions to steering input. If you’re after more responsive handling, you probably have a couple of roadracing championships under your belt. Road riders, like myself, will appreciate the tube handlebar and user-friendly controls that supplant previous Buells’ funky clip-ons and switchgear. Also revised is the sidestand, a major improvement in my opinion. Now, if they could just fix the seat....

Pre-production flaws aside, Erik Buell and company have a winner on their hands here. 1 want one.

-Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

THE GOOD: THIS THING IS A STONE GAS to ride. Remember last month’s KTM Duke? Well, lower the cg and pump in an additional 30 horsepower, and you’ve got the SI. Bonus points to the Uni-Planer rubber-mount system, too.

The Bad: That’s not a seat, it’s a suppository. Whoever designed it should be force-marched to remedial anatomy class-or be made to actually sit on it for more than 15 minutes.

The Ugly: Erik, Erik, Erik, what is the deal with that wonky bobtail rear end? Look. I’m all for passionate styling, for being different, for making a statement, but this is passion without purpose. And, yes, 1 applaud the freebreathing, well-muted exhaust; I know its under-engine location eliminates cornering-clearance worries. But why does it have to look like something filched from an abandoned Baja Bug?

Luckily, the SI Lightning’s Good wins out over its Bad-now, can we do something about the Ugly?

-David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue